Part Four: A Brief History of Booze

By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

Beaver County, like the Mississippi River or the Appalachian ridges, was shaped by natural forces: glacial melt, river erosion, tectonic plates—and alcohol.

To leave alcohol out of the county’s natural history would be like writing about Buttermilk Falls and skipping the water. The earliest settlers understood this. At Fort McIntosh in 1778, the federal government issued whiskey rations not as a perk but as a survival tool. Soldiers without whiskey tended to mutiny, or worse, write letters to Congress. Settlers, no less practical, built taverns at every crossroads. You might say they were America’s first co-working spaces, only with more cider and less Wi-Fi.

Appleseed and the Whiskey Tax

Enter Johnny Appleseed, a charismatic fellow (real name: John Chapman) who planted orchards across the Ohio Valley in the early 1800s. Schoolchildren are told he was a kindly mystic spreading wholesome fruit. In fact, he was a hard-nosed entrepreneur supplying raw material for cider—fermented, potent, and far more interesting than Red Delicious. His orchards didn’t feed anyone so much as they kept everyone just tipsy enough to drink the water without complaint.

By the 1790s, the region was producing so much whiskey that the federal government felt compelled to tax it. Thus the Whiskey Rebellion—a three-year protest by farmers who could not understand why George Washington, once a comrade in tavern politics, was suddenly sending an army to collect the bar tab. Beaver County wasn’t yet on the map, but the lesson lingered: when Washington says “last call,” put down your mug.

The Harmonists: Whiskey Without Drinking It

Industrial alcohol came early here. The Harmony Society—those industrious German Pietists who built Economy (today’s Ambridge)—added a distillery in 1827 to their catalog of iron foundries, rolling mills, and textile works. Their “Old Economy Whiskey” became famous for its quality, even as their founder George Rapp condemned alcohol as a moral evil.

The contradiction wasn’t carelessness, but policy. Rapp’s 1805 constitution flatly banned members from drinking spirits, except medicinally. In his 1824 Thoughts on the Destiny of Man, he went further: “The use of ardent spirits is a great evil, leading to idleness, poverty, and crime; it must be forsaken for the sake of the soul’s salvation.” Yet the Society continued to distill whiskey, not for themselves, but for the outside world. The profits sustained their self-sufficient economy.

They reconciled principle with pragmatism by drawing a hard line: production was commerce, consumption was corruption. Members might take “Boneset Cordial” for fevers or, in rare cases, a dram during construction when storage failed. Otherwise, abstinence was law. The Harmonists thus managed the unusual feat of being both premier whiskey makers and model temperance advocates—a balancing act Beaver County has admired and imitated in its own inconsistent way ever since.

Likewise Geneva College, founded in 1848 by the Reformed Presbyterian Church, made sure its students were not merely educated but upright. The school banned drinking, smoking, and even “round dancing,” a form of innocent Terpsichore apparently considered one pirouette away from perdition. These strictures gave Geneva the air of a monastery with football. While the students learned their Greek and calculus, they also learned the wages of sin included suspension—sometimes over a cigarette, occasionally over a foxtrot.

Saloons, Temperance, and Tall Tales

By the late 19th century, the saloon was the county’s social nerve center. A man could finish a twelve-hour shift at J&L, stop for a schooner of beer, and, before the second round, find himself signed up for a union. Employers called saloons dens of idleness. Workers called them headquarters.

It was also in the saloon era that Ambridge acquired its most persistent boast: residents will swear on their mother’s grave that The Guinness Book of World Records once declared their town to have more saloons per capita than any place on Earth. It sounds plausible. But nod politely and ignore them.

Meanwhile, temperance crusaders sang hymns in New Brighton while mill hunks sang drinking songs in Beaver Falls. Both sides were equally earnest, though only one side had brass bands.

Prohibition, Dry Beaver, and Wet Bridgewater

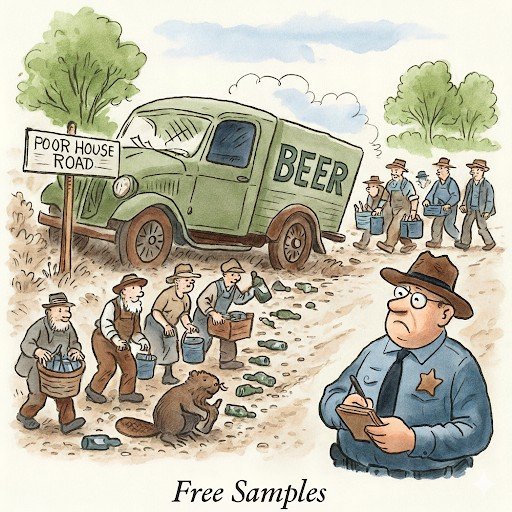

The reformers finally had their day on January 16, 1920, when Prohibition arrived. America swore off alcohol. Beaver County, ever inventive, responded by turning barns into stills, hotels into underground wineries, and back roads into distribution channels. One unfortunate truckload of Canadian beer overturned on Poor House Road in Raccoon Township, and within an hour the entire contents had been redistributed to grateful citizens. Economists later called Prohibition a failure. Beaver County called it “free samples.”

After repeal in 1933, the county celebrated by opening more than 300 taverns in two years.

But not every borough welcomed them back. Beaver, bowing to temperance sympathies and

local referendums, went dry—an act of moral courage, or perhaps self-sabotage. Next door,

Bridgewater stayed wet. It had been wet since the canal days, when Dunlap’s and Ankeny’s

hotels refreshed canalmen and steamboat crews. Later, Kelly’s Riverside Saloon and its

cousins became the go-to watering holes for Beaver residents who, like parched pilgrims,

had only to cross the r