By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher

Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

The Beaver–Monaca Railroad Bridge may look like just another big steel truss over the Ohio River, but when it opened in May 1910 it was something more: a professional rebuttal.

Its designer, Albert Lucius, had once worked for the Phoenix Bridge Company—the same outfit whose engineers had presided over the world’s deadliest construction disaster just three years earlier at Quebec.

On August 29, 1907, the Quebec Bridge collapsed into the St. Lawrence River with a roar that echoed through the entire engineering profession. Seventy-five men died, cantilever bridges suddenly looked like death traps, and Phoenix Bridge Company’s reputation lay in twisted steel alongside Theodore Cooper’s.

And then along came Lucius, who had left Phoenix back in 1886 to run his own consulting practice. By the time the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie Railroad tapped him to span the Ohio between Phillipsburg (now Monaca) and Beaver, Quebec’s ghosts still hung in the air. Lucius knew the men involved—Peter Szlapka, John Deans, Theodore Cooper—if not personally, then professionally, through the same small fraternity of bridge builders and journals like Engineering News. He knew what had gone wrong. And he knew he had something to prove.

The Man with the Math

Born in Germany in 1844, Lucius immigrated to America in 1865 and cut his teeth designing elevated railways in New York. By the 1880s he was working for Phoenix Bridge Company, mastering the heavy steel fabrication that would make or break an engineer. He founded his own firm in 1886 and spent the next two decades building a reputation for designs that were conservative, sturdy, and—most importantly—still standing.

When Quebec fell, Lucius had been independent for over 20 years. But he carried the Phoenix pedigree, and with it a professional stake in proving that cantilever bridges weren’t inherently doomed—only badly executed.

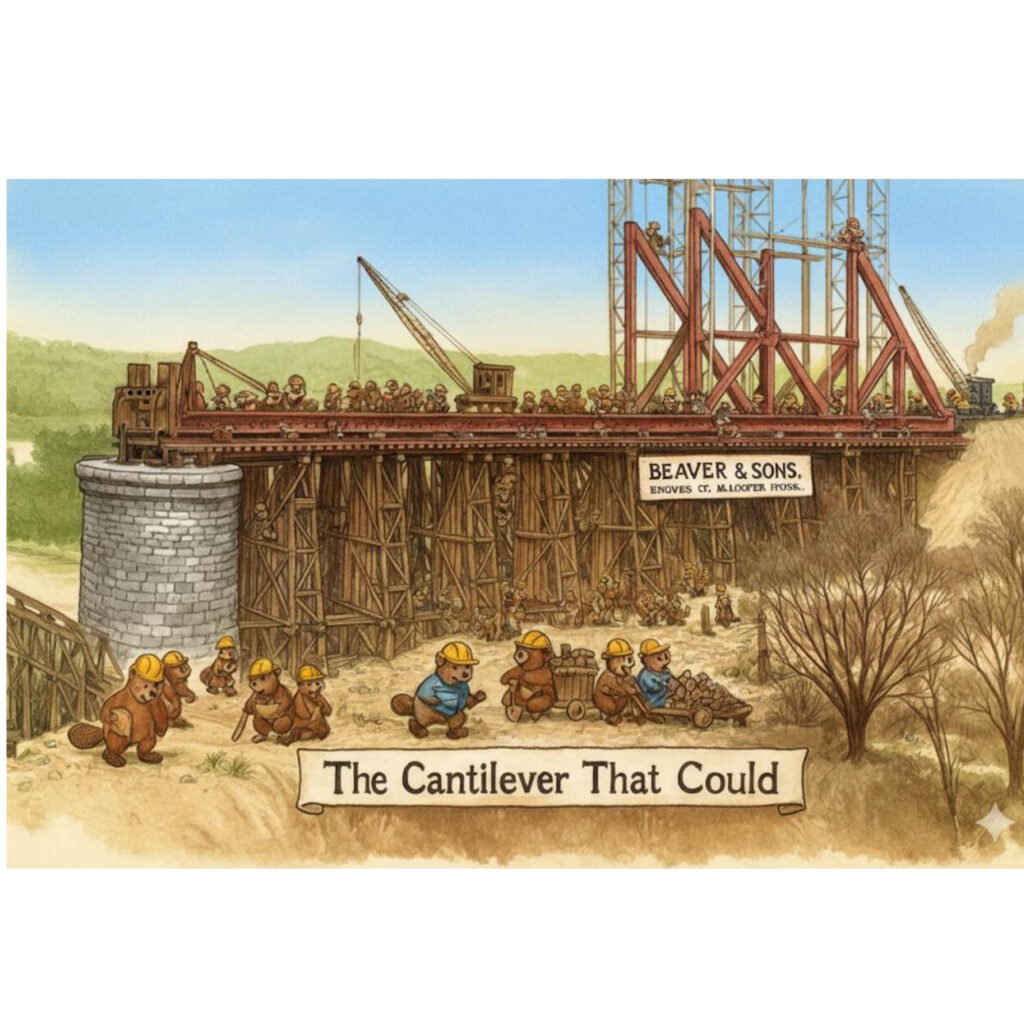

The Cantilever That Could

The Beaver–Monaca Bridge was a cantilever, yes—but one with humility baked into its steel. At 1,779 feet, with a 769-foot main span, it was among the largest of its kind. Its Baltimore truss was deep and subdivided, built to resist the buckling that had crippled Quebec’s compression chords. Its stresses were conservative, its members heavy, its innovations practical rather than flashy: wedge bearings to soften the pounding of anchor arms, unreinforced concrete caissons sunk by Dravo, and a custom traveling crane that let the structure grow out over the river without falsework or “enormous erection stresses.”

McClintic-Marshall’s crews checked deflections daily, riveted every panel in place, and ignored the temptation to shave margins thin. By the time it opened in May 1910, the bridge had done more than connect Beaver to Monaca. It had salvaged the cantilever’s reputation.

Quebec’s Ghost

The Quebec collapse was caused by over-optimistic stress limits, underestimated dead loads, and absentee oversight. Lucius’s bridge avoided all three: lower allowable stresses, constant recalculation, and engineers on site every day.

He didn’t reinvent the form—he simply did it properly. Where Quebec was bold and brittle, Beaver was conservative and steady. If Quebec was hubris, Beaver was humility.

A Station Left Behind

While the bridge kept its purpose, Beaver Station did not. Passenger trains stopped running July 12, 1985, leaving the building to a second career. From 1986 to 2010, the passenger depot became Beaver County’s 911 center. Today, thanks to the Beaver Area Heritage Foundation, it serves as a Cultural and Event Center.

The bridge never needed reinvention. It just kept hauling.

Still Standing

Albert Lucius didn’t shout about his success. He simply built a bridge that worked. More than a century later, freights still pound across it daily under CSX, rivets still tight, trusses still true.

Quebec collapsed in 1907. Beaver opened in 1910. Guess which one is still carrying the load.

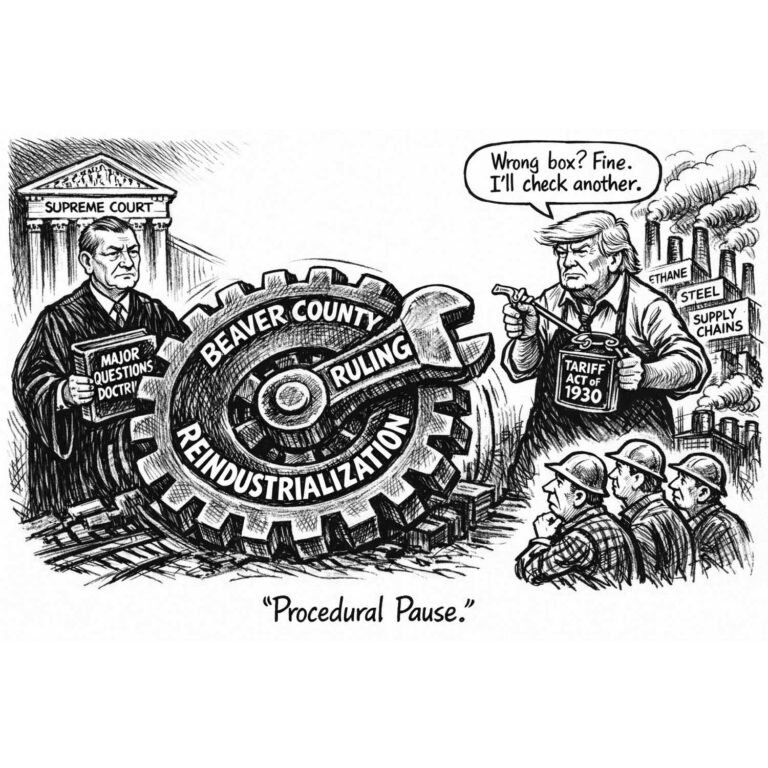

What the Bridge Says About Beaver County Today

If the Beaver–Monaca Bridge was Albert Lucius’s quiet rebuttal, today it reads as a county’s declaration. More than a century on, its riveted steel still carries trains loaded with the raw materials and finished goods that define Beaver County’s industrial backbone. It’s a reminder that in a place often written off as past its prime, things built to endure still do.

The bridge embodies a local temperament: skeptical of flash, distrustful of shortcuts, but proud when the work holds up. Like the county it anchors, it is less about spectacle than persistence—about carrying the load, day after day, without flinching.

Beaver County has reinvented itself many times—steel to energy, mills to robotics, coal smoke to data centers. But through it all, the bridge has stood in the middle of the river, steady as ever. It suggests that the county’s real strength isn’t just in reinvention. It’s in endurance.