By Rodger Morrow, Beaver County Business Editor & Publisher

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

Once upon a time, Pittsburgh dreamed big. It dreamed of glass towers rising where smokestacks once stood, of sleek “innovation corridors” replacing the mills that paid for Carnegie’s libraries and Mellon’s mansions. And then—like so many dreams—it rolled over, hit the snooze button, and started filling out grant applications for more “affordable housing.”

Today, the city’s “master plans” read like architectural fan fiction: lush renderings, visionary buzzwords, and acres of nothing. The latest example is the Lower Hill District, where a 40-acre redevelopment plan—announced with fanfare more than a decade ago—has so far produced exactly two things: the FNB Financial Center and a Live Nation concert hall. Everything else remains a prairie of parking lots and press releases.

When Planning Becomes a Substitute for Progress

The Lower Hill’s development rights are held by the Pittsburgh Penguins, who are rumored to be for sale—because, of course, nothing says “economic stability” like a hockey team negotiating with a redevelopment authority. The rest of the plan—two office buildings totaling 360,000 square feet—is frozen in the amber of 2019, back when we still thought people might return to the office someday.

As State Senator Wayne Fontana put it, “It’s almost to the point where we’re starting over.” Translation: we’re not starting over—we’re just stuck.

A City That Mistook Housing for Growth

Across the city, the same story plays out. Developers such as Oxford Development and Piatt Companies are rewriting their plans not to expand employment, but to add yet more apartments. The 3 Crossings project in the Strip District—originally four shiny office buildings—is now destined to become a collection of six-story apartment blocks with 350 units, 20 townhouses, and a few shops selling artisanal dog biscuits.

Meanwhile, at Hazelwood Green, the long-promised “innovation campus” is still being discovered by archaeologists, and the Esplanade on the North Side—once billed as a billion-dollar waterfront playground—has been scaled down to a “lean” $740 million, featuring 1,000 residential units and, mercifully, a Ferris wheel. (Nothing says “economic renaissance” like a giant rotating symbol of going nowhere.)

A Plan for Every Parcel, but a Vision for None

To their credit, the developers are adapting. The pandemic made office towers as appealing as tuberculosis wards. But the city itself—still boasting of “equitable growth” while quietly losing its tax base—has confused adaptability with surrender.

The grand plan now seems to be housing, health care, and hope—which is to say, Pittsburgh is betting its future on people getting older, sicker, and poorer. That may make for a bustling hospital district, but it doesn’t build a tax base or keep the lights on.

Crime, Taxes, and the Soft Bigotry of Low Expectations

And then there’s the small matter of crime. Walk down Liberty Avenue after dark and you’ll discover that “mixed-use development” means retail by day and police tape by night. The city’s leadership, when not proposing new commissions to study old failures, has mastered the art of issuing statements of “ongoing concern.” The problem with ongoing concern, of course, is that it eventually turns into gone concern.

Developers know this. So do employers. Which is why, quietly but steadily, the smart money is flowing north—to Beaver, Butler, and Lawrence Counties—where land is cheaper, crime is lower, and local officials still return phone calls.

Beaver County: Where Plans Still Mean Something

While Pittsburgh keeps revising blueprints for imaginary towers, Beaver County is actually building things—data centers, manufacturing plants, switchgear factories, and even a nuclear-energy test facility that could power half of Western Pennsylvania. Over here, “mixed use” means engineers and electricians working the same shift, not yoga studios next to poke-bowl shops.

Butler County is attracting logistics and distribution centers faster than the city can schedule another “stakeholder roundtable.” Lawrence County is reviving its industrial corridors with energy and ag-tech investment. In other words, the periphery has become the center of gravity—because it’s still grounded in reality.

The Economic Geography of Self-Sabotage

Every time Pittsburgh’s planners announce a new “visioning session,” another manufacturer looks at Beaver County and says, “They still know how to pour concrete over there.” It’s not that people don’t love Pittsburgh—we all do. It’s just that love alone doesn’t keep the cranes moving.

A region that once built the world’s bridges is now afraid to cross its own. It has mistaken process for progress and planning for production. The result is a city slowly zoning itself into irrelevance—while the counties it used to patronize are quietly eating its lunch.

The Final Irony

If you want to see the future of Pittsburgh, don’t go to the Lower Hill. Go to Beaver County, where you’ll find new manufacturing jobs, actual economic growth, and fewer bullet holes per square foot.

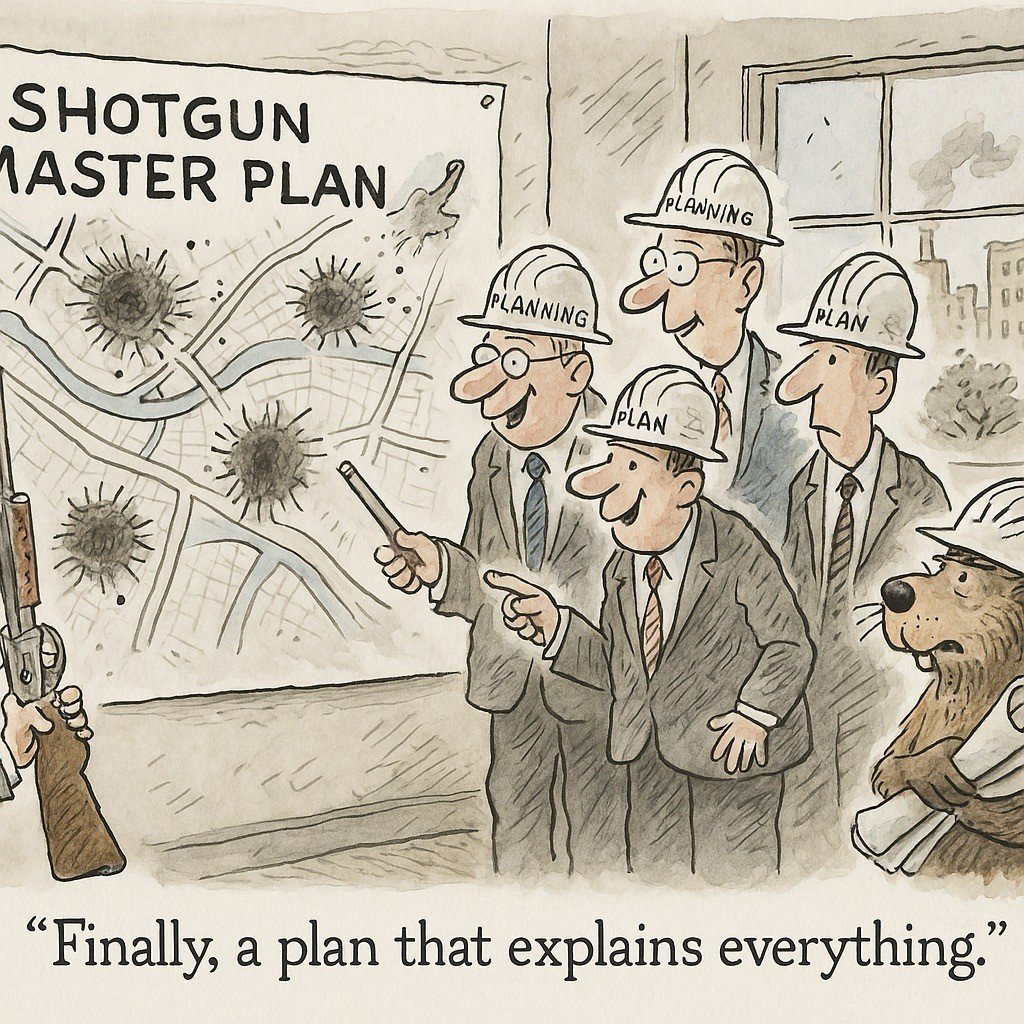

Pittsburgh’s master planners aren’t just shooting themselves in the foot—they’re using a shotgun, and the blast radius extends well past Grant Street.