By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher, Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

ZELIENOPLE — If you’d told me ten years ago that a wildlife biologist, a private-jet executive, and a onetime tech nomad would join forces to rebuild small-town Pennsylvania one condemned building at a time, I’d have suggested you lay off the motivational podcasts.

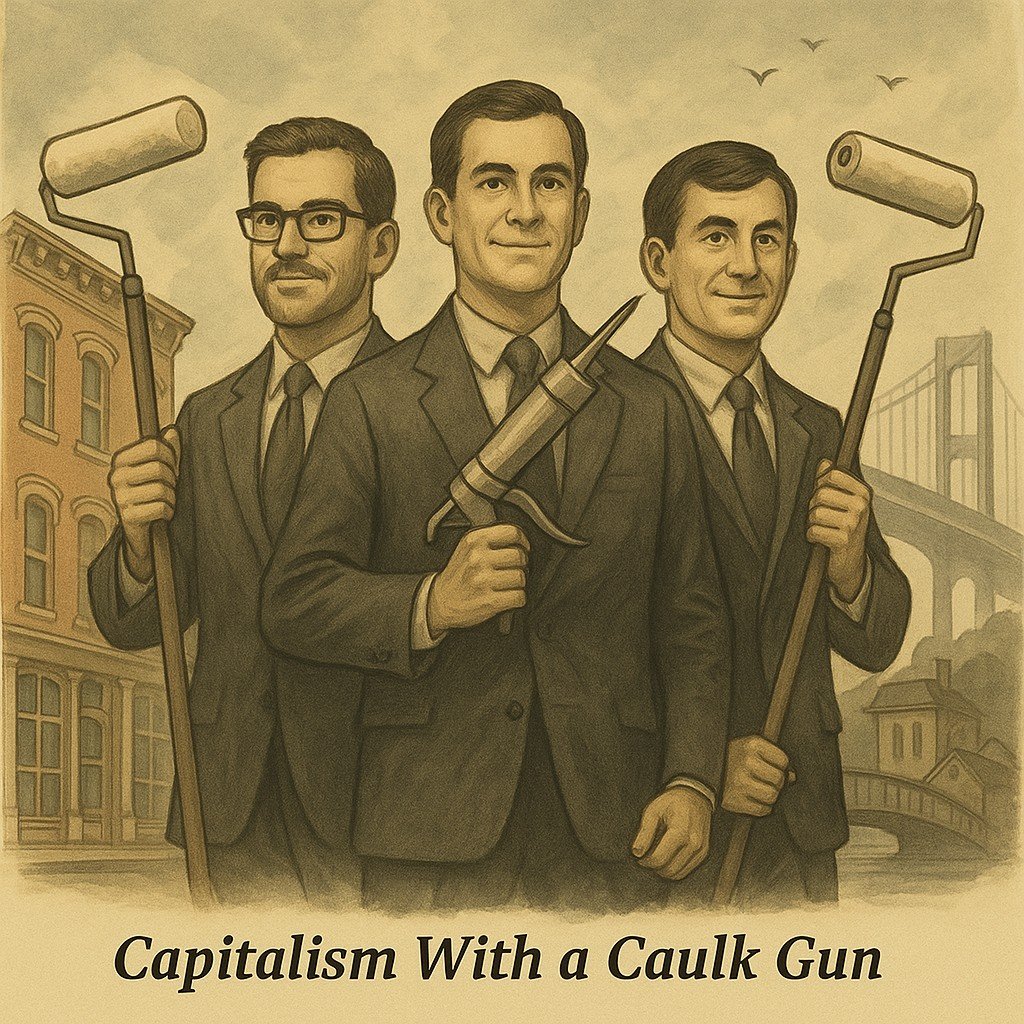

Yet here we are, on a bright November afternoon in Zelienople, watching Eric Rice, Patrick Rice, and Clayton Pegher quietly turn derelict properties into habitable neighborhoods. Their company, Rice Pegher Capital, calls itself a “boutique commercial real-estate investment firm.” What it really is — at least around here — is an unpretentious experiment in civic renewal with an occasional profit attached.

How the Band Got Together

Eric Rice caught the real-estate bug in 2008 while unloading foreclosures for the late, lamented Countrywide Financial. By 2015, he and his brother Patrick were buying and fixing up single-family homes — a few “fix and flips,” a few “fix and holds” — and discovering they liked the process almost as much as the product.

In 2016 and 2017, the brothers began educating themselves in the subtler arts of multifamily and commercial property. After six or eight months of this crash course in capitalism, they invited their friend Clayton Pegher — the local aviation mogul and CEO of the Private Jet Center at Zelienople Airport — to help them take down their first major deal, the Coraopolis Portfolio.

They emerged with their shirts, their sanity, and the novel conviction that the partnership just might work.

The Missing Middle and the Forgotten Towns

Rice Pegher Capital builds for what economists call workforce housing — apartments for people who make too much for subsidies and too little for mortgages. These are the nurses, lineworkers, and clerks who keep the economy’s middle upright while everyone else argues about it.

Their chosen hunting grounds lie along the I-79 corridor — Butler, Beaver, Zelienople — the kind of towns the big developers ignore because the zoning officer still answers the phone and the mayor might show up with a folding chair for the ribbon-cutting.

“We’re not building luxury towers,” Eric told me. “We’re building good apartments for good people.” And he means it: most of their units feature granite countertops and careful finish work. The trick is that they deliver high-quality spaces below luxury-price expectations, thanks to a tight network of vendors and in-house design and construction management. The result is thoughtful housing that looks expensive but rents like reality.

The Reverse Broken-Windows Theory

If you want to see what they mean, drive through New Brighton or Rochester. When they bought what locals politely called “a problem property,” it was the kind of place most people condemned with a shudder.

Eighteen months later the 62 apartments had been gutted, rebuilt, and restored. Within another six months, the entire portfolio was leased. The police chief reported that calls for service had dropped 20 percent borough-wide. The borough, in a fit of civic gratitude, even paved the road leading to the complex — a thank-you disguised as infrastructure.

That’s what the partners call their reverse broken-windows effect: fix one place up, and suddenly the neighbors start mowing again. It’s urban renewal without the bulldozers — and without the deficit spending.

The Visionary, the Integrator, and the Aviator

Inside the firm, the chemistry is as deliberate as the carpentry.

Eric Rice is the company’s visionary — the one Patrick describes as possessing a “reality-distortion field,” the kind Walter Isaacson once ascribed to Steve Jobs — except applied to real estate and, mercifully, without the tantrums. His optimism and drive form the foundation of the company.

Patrick Rice is the integrator, the steady hand turning Eric’s vision into blueprints, spreadsheets, and signed leases. Together they shaped the company’s workforce-housing thesis — a quietly radical idea in an age of gold-plated rentals.

And Clayton Pegher, while not involved in daily operations, plays a strategic role in financing and high-level deal structure — the ballast that keeps the partnership aloft.

Scaling Up Without Selling Out

From those first rehabs, the firm has grown into a vertically integrated enterprise that handles everything from drywall to rent collection. As of this week, they’re closing another round of acquisitions that will bring total assets under management to roughly $50 million — a long way from the fix-and-flip days of 2015.

Employees are invited to invest alongside the partners, dollar for dollar — a policy that would make most HR departments reach for a sedative. “We want everyone to have a seat at the cap table,” Eric said. It’s capitalism with a small-town conscience.

A Region Ready to Rise Again

The partners like Beaver County’s odds. They see the Shell cracker plant and the Bruce Mansfield power plant complex not as one-offs but as a 30-year engine that will keep drawing workers who need decent housing. They’re less enchanted with downtown Pittsburgh, which they describe as “multiples harder” to develop — an economist’s way of saying no thanks.

So they stick with towns where the mayor calls you back and the borough manager remembers your name. Wall Street may not swoon, but north of the Ohio River the math works.

A Main Street With a Future

In Zelienople they’ve been stripping away the cedar shingles and vinyl siding that long hid the town’s handsome brickwork. One of their first local projects — a boarded-up Italian restaurant — is now a tidy building of offices and apartments. Next week they’ll close on a 152-unit portfolio in Baden.

Stand on the sidewalk and you can hear hammers, smell paint, and maybe catch the faint scent of hope — that elusive regional commodity we’ve been short on since the mills went quiet.

The Takeaway

Recovery rarely arrives in a motorcade of ribbon-cuttings and press releases. More often it shows up in coveralls, carrying a bucket of paint.

The men of Rice Pegher Capital aren’t reinventing Beaver County so much as reminding it what decency looks like — clean halls, working lights, and a rent check that clears. It’s not glamorous, but neither is western Pennsylvania, most days.