By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher, Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

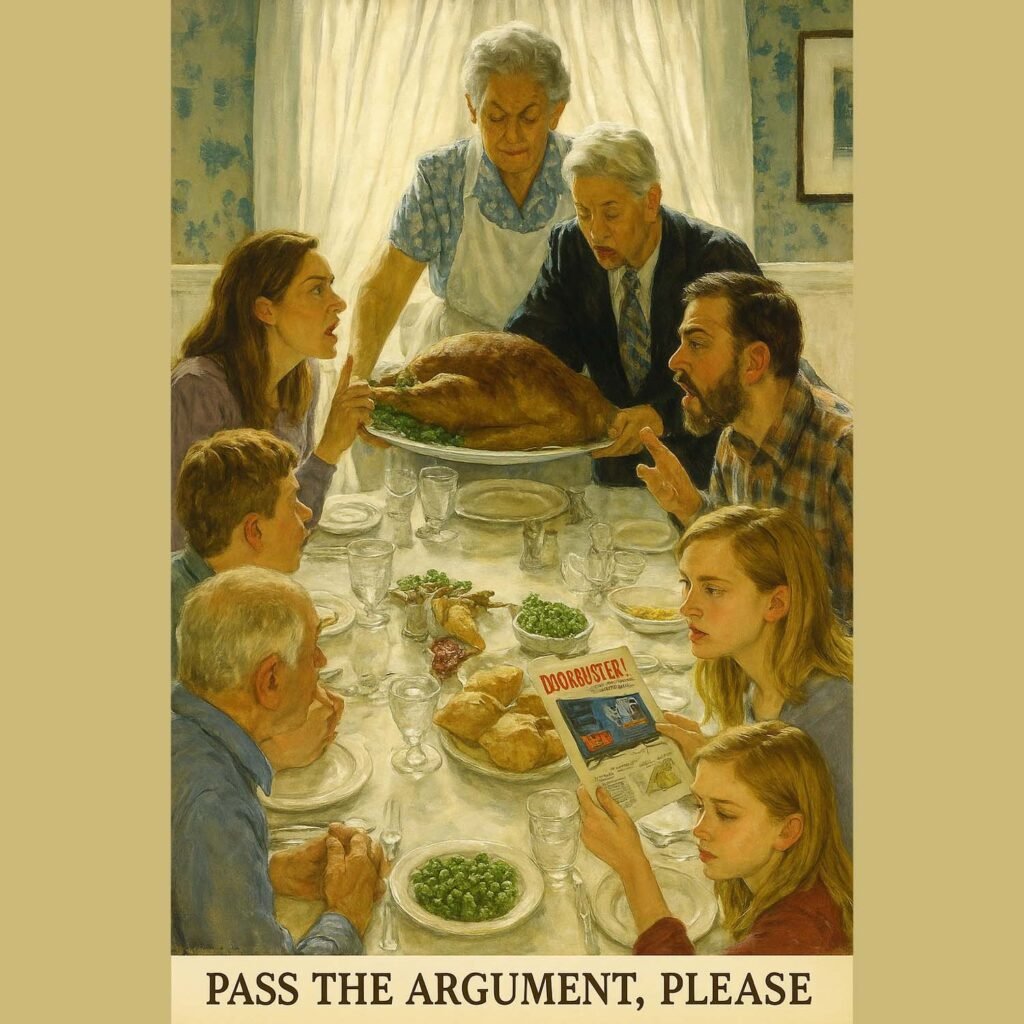

Before our great national celebration

Before our great national celebration of gratitude was demoted to the day before Black Friday, Beaver County observed Thanksgiving with the unhurried earnestness of a people who considered gratitude a year-round occupation rather than a commercial layover between pumpkin spice and peppermint. You can practically hear the ancestors sighing whenever someone now announces that they’re “pre-gaming for Black Friday” by carb-loading on mashed potatoes.

The truth is, Beaver County had been giving thanks long before Lincoln made it fashionable and before retailers weaponized it. The tradition began in the era when the county wasn’t even Beaver County yet—just a stretch of wilderness between the confluence of two rivers and the anxiety of every settler who had just discovered how cold a western Pennsylvania winter could get. In those days, a “day of thanksgiving” meant the crops survived, the roof didn’t cave in, and the raccoons—God’s own criminal element—hadn’t eaten all the turnips.

Even earlier, when Logstown bustled as a mid-18th-century trading hub along the Ohio, colonial traders and Lenape families sometimes shared post-harvest meals whose spirit (if not the menu) would have felt familiar to a modern reader. There is no record of anyone showing up with green-bean casserole, which proves the past was not without mercy.

By the time Beaver County was officially carved out

By the time Beaver County was officially carved out of Allegheny and Washington counties in 1800, settlers of Scotch-Irish and German stock had turned these informal thanks-givings into fall customs: pierogies beside roast venison, root vegetables beside whatever game hadn’t outrun the family patriarch. The Pennsylvania Dutch influence meant that if you could pickle it, bake it, or accidentally ferment it, it went on the table.

Actual Thanksgiving—the capital-T, federally sanctioned holiday—arrived courtesy of Sarah Josepha Hale, the Philadelphia editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book, who spent decades lobbying for a national observance. She is the unheralded patron saint of every overworked mother now Googling “emergency gravy fixes.” Lincoln finally obliged in 1863, and Beaver County adopted the holiday with the determination of a people who had much to mourn and much to be grateful for.

The Civil War years

The Civil War years brought some of the earliest large-scale local observances. Beaver Borough’s churches—Trinity Episcopal among them—hosted Thanksgiving dinners for returning soldiers and grieving families. In New Brighton, the 1864 “Grand Thanksgiving Banquet” raised funds for war widows and managed to serve a meal large enough to astonish even modern Beaver Countians, who know a thing or two about portions. Local newspapers like The Argus covered these events in reverent tones, as though gratitude itself might reduce the casualty lists.

Industrial era traditions

The county’s 1900 centennial celebration wasn’t technically Thanksgiving, but you’d never know it from the photographs: tables groaning under turkey roasts, agricultural floats parading down Beaver’s streets, pies of such alarming diameter that OSHA would intervene today. Composer J.S. Duss even contributed a “Festival March,” presumably written to help attendees reach the dessert table before collapsing. Governor William A. Stone showed up, proving that even Harrisburg can’t resist a well-executed turkey roast.

As the 20th century industrialized the county—Jones & Laughlin in Aliquippa, the Beaver Falls mills, and factories humming from dawn to exhaustion—Thanksgiving became both a reprieve and a performance. Companies hosted dinners for workers in the 1920s and ’30s, sometimes for thousands. One Beaver Falls steel mill fed 1,200 people in one sitting, an early demonstration of what Americans can achieve when properly motivated by gravy.

Wartime and beyond

During World War II, ration-book Thanksgivings returned the holiday to its frontier roots. Victory gardens supplied the vegetables; community halls supplied the patriotism. Rochester’s 1942 supper honoring draftees drew over 500 people—an impressive feat considering that half the county was working shifts that didn’t acknowledge the existence of holidays.

By the 1950s and ’60s, Thanksgiving became a charitable engine. Optimist Clubs and churches organized “Turkey Trots” and food baskets, culminating in the 1963 centennial tribute to Lincoln’s proclamation. The 1978 Beaver Falls initiative fed 300 families and helped establish the county’s still-active pantry programs—quiet traditions that don’t make headlines but keep neighbors afloat.

Thanksgiving today

Today, Thanksgiving in Beaver County remains—in its stubborn, unflashy way—exactly what it was in 1800: a celebration of resilience, community, and the peculiar joy of surviving another year together. Heritage reenactments echo the 19th century; Shadow Lakes offers buffets with carving stations Ernest Hemingway might have wept over; and every township still finds a way to fuse a church supper with a tree lighting, usually by asking the same volunteers to do both.

So yes, the holiday may now live in the shadow of Black Friday’s neon-lit chaos. But here, between the rivers and the mills and the memories, Thanksgiving keeps its footing. It comes back every year—sometimes quietly, sometimes with more pies than medically advisable—reminding us of who we were, who we are, and what we still have to be grateful for, even when the sales start at 6 p.m.

Just don’t tell the Pilgrims about that part. They suffered enough.