By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher, Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

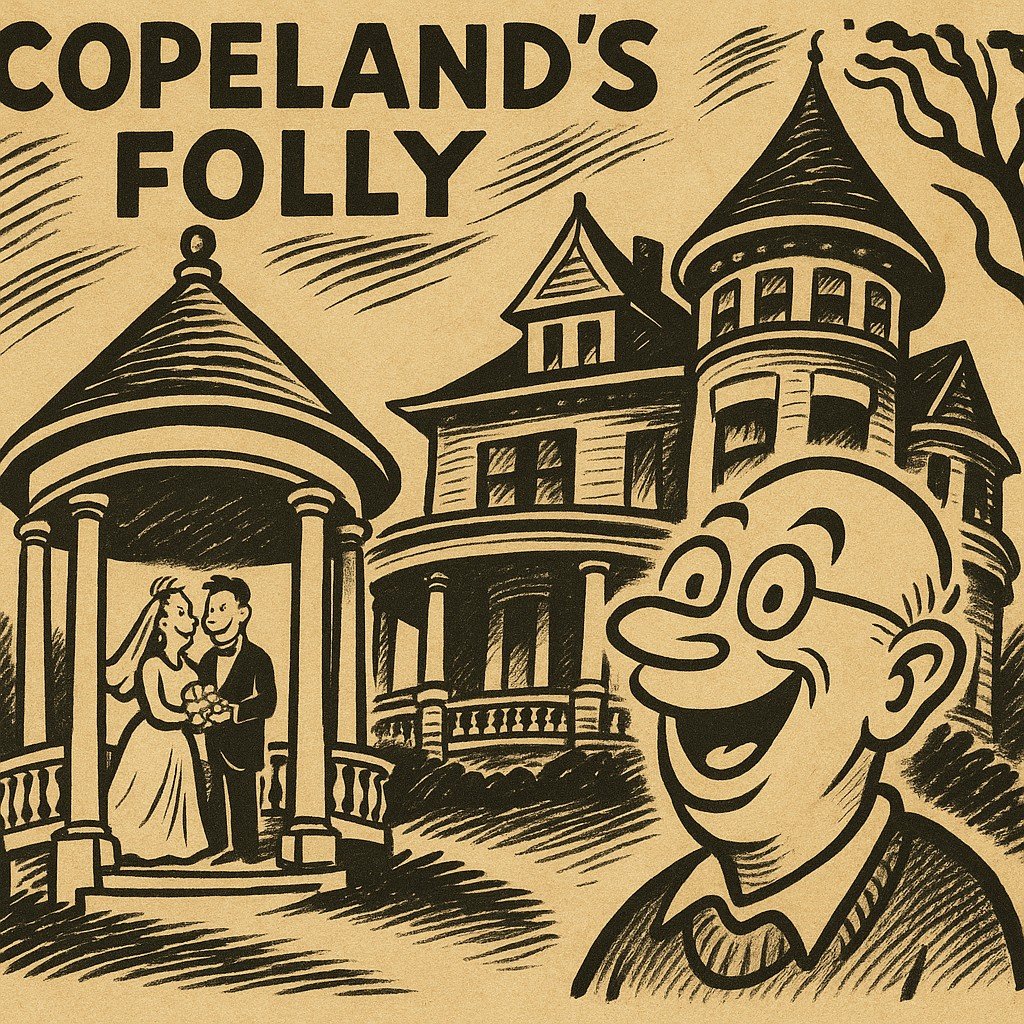

Beaver’s Unlikely Belvedere

In most towns, historic preservation means putting up a tasteful plaque, planting a tree, and hoping the tree doesn’t die before the next grant cycle. Beaver, however, does not suffer from a shortage of people who regard the laws of physics—and occasionally Borough Council—as friendly suggestions rather than constraints. That’s why, on a small lawn beside our railroad station, there now stands a Belvedere roof rescued from a house that no longer exists, rebuilt on columns that never belonged to it, illuminated in colors once reserved for Las Vegas, and kept upright largely through stubbornness and concrete.

I am referring, of course, to the Cunningham Belvedere, the improbable architectural orphan that the town’s “Everyman, Everywhere” Chuck Copeland once described—as modestly as possible—as “something our community couldn’t even imagine it wanted.”

The Cunningham House

The story begins in 1895, when Beaver attorney James Hamilton Cunningham—a man who had survived the Civil War, Andersonville Prison, and farm labor—decided life didn’t need to be comfortable so much as symbolic. He already owned a respectable home on Beaver Street, but respectability is cold comfort when your mother moves in. So Cunningham hired courthouse architect Thomas Boyd and set about building a Queen Anne mansion on Second Street that could house his family, his mother, and the entirety of Beaver County’s legal ambitions.

Boyd delivered in style. The house boasted 6,000 square feet, two towers (one round, one octagonal), curving Roman brickwork, carved fireplaces in practically every room, and porches on three floors. It was the sort of house one built to make a point. The point, roughly translated, was: Look upon my curved banisters, ye mighty, and despair.

For several decades, the house served its purpose. Then Beaver’s wartime boom arrived, and the mansion—like so many others—was chopped into a warren of apartments to house workers from the Curtis-Wright propeller plant. Room by room, door by door, Cunningham’s grand vision became a kind of architectural boarding house for industrial necessity.

By the 2000s, the building was long empty, unheated, and shedding plaster as enthusiastically as a sycamore tree sheds bark. When the property changed hands, the new owner had all the nostalgia of a demolition permit. In 2014, the wrecker’s ball began its slow approach.

Saving What Could Be Saved

This is where Chuck Copeland and the Beaver Area Heritage Foundation wandered into the story—because when something looks doomed, this group becomes emotionally attached to it.

The house was clearly impossible to save as a house. Zoning blocked commercial reuse. No family with 14 bedrooms on their wish list had been seen in the county since 1912. And the place had more custom millwork than market value.

So Copeland and his merry band of preservationists made the sensible decision: They would dismantle the good parts and store them in Chuck’s garage.

A dozen carved mantels, stained glass windows, eyebrow windows, door frames, paneling, archways—everything that could be unscrewed, unbolted, or gently pried loose made its way into Copeland’s cavernous storage like a Victorian organ-donor program. The front door alone—48 inches of beveled and leaded glass framed in tiger maple—nearly became the showpiece of the Beaver railroad station until the Museum Commission intervened, because nothing ruins a station’s historical integrity like a door two feet too fabulous.

Eventually, the demolition crew reached the roof—the magnificent, tower-topping conical crown of the octagonal turret. And that, as Copeland tells it, is where he had his epiphany. Driving his mother to Florida, somewhere between West Virginia and a cell-phone dead zone, he suddenly realized they should save the roof.

Moving the Roof

To remove a 10,000-pound roof, one needs certain things:

- A demolition contractor willing to take phone calls from a man on I-77

- A crane operator with a high tolerance for liability

- Floor joists salvaged from a 1990s bank demolition

- A willingness to cut around a tower with a chainsaw while pretending this is normal

Miraculously, all these elements existed in Beaver County.

With floor joists slid through the third-floor windows, chainsaws buzzing, and cranes groaning, the crew lifted the turret roof into the air and lowered it onto a waiting lowboy trailer. The finial snapped off, but this was deemed acceptable, as everything else was already insane.

Then came the parade.

Down Bricker Road, turning onto River Road, past South Lincoln, under wires lifted by a man standing on a pickup truck, the roof crept slowly toward its temporary home beside the train station. Onlookers lined the streets, presumably unsure what denomination of religion this safety-vest procession belonged to.

And there it sat. For three years.

The Belvedere Is Born

By 2015, Borough Council had grown weary of hosting a 10,000-pound lawn ornament. A few members suggested burning it.

Copeland, recently retired as Borough Manager, decided the moment had come to turn the roof into something useful.

The Foundation’s late Bob Smith built prototypes showing how the Belvedere might look. The models showed promise—and also that the project would require an architectural firm, structural engineers, concrete foundations, steel beams, fiberglass columns, new rubber shingles, copper flashing, electrical conduits, and an extraordinary amount of Beaver County teamwork.

The construction unfolded like a very long magic trick performed by union contractors prepared to be amazed by their own sorcery.

Engineering the Impossible

The roof was reinforced from the inside. Concrete piers were installed with planetary precision. Steel beams were placed. A massive crane swung the roof onto the waiting columns.

Then engineers discovered the structure could torque. The solution was to fill the fiberglass columns with concrete.

The crew installed rubber-slate shingles, copper flashing, and lightning protection from a new cast-copper finial crafted in Copeland’s workshop.

Inside, plasterers worked through cold days; electricians installed LED lights capable of producing any color.

The Finished Landmark

On a snowy day in March 2017, the Belvedere stood ready for use.

The dedication brought out contractors, engineers, volunteers, and curious residents. People now stroll up the ramp, admire the glow, and take wedding photos—never guessing the roof once crept through town on a flatbed truck.

What began as a doomed turret is now one of Beaver’s most beloved landmarks—proof that when the town’s craftsmen, volunteers, and preservationists join forces, something wonderful can happen.

The next project—a 66,000-pound caboose—is already being whispered about. In Beaver, history doesn’t rest. It gets moved, rebuilt, repainted, and lit in LED.

Preservation in Beaver County works best when it makes absolutely no sense at all.