By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher, Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

The New Lords of the Realm

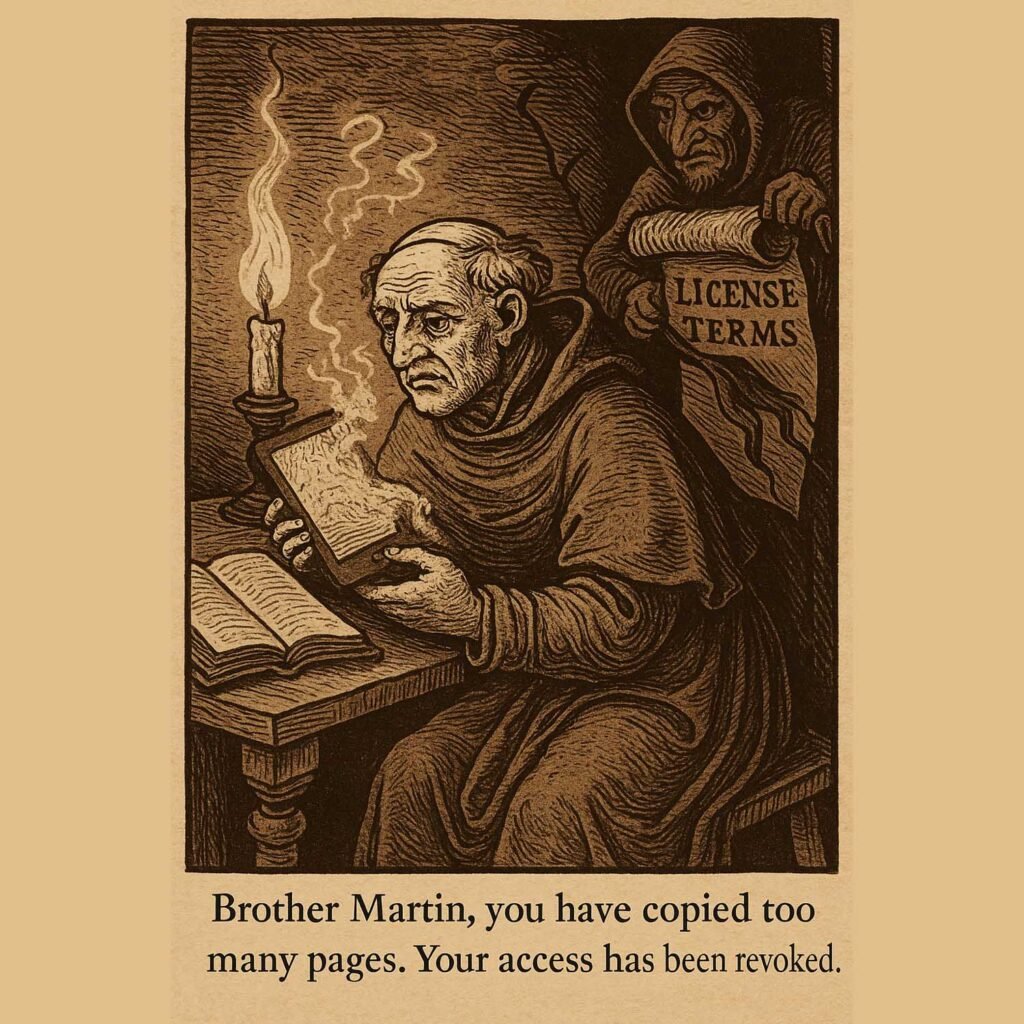

Somewhere in Silicon Valley, a group of well-paid futurists is congratulating itself for having finally solved the ancient problem of book ownership. After thousands of years of humans buying, borrowing, passing down, and occasionally losing their books, we have at last perfected a system in which no one owns anything at all—not even the things they’ve already paid for. It is, I grant you, a remarkable achievement. Medieval clerics would be proud.

For those who missed the memo, we now live in an age when the average library “collection” is a vast kingdom of ghosts—six million flickering ebooks at Penn State alone—each one present only so long as the publisher allows it. A physical book, you may recall, is something you can drop on your foot, loan to a friend, or accidentally leave on the picnic table at Hank’s Frozen Custard. An ebook is something your library rents from a multinational conglomerate in exchange for annual tribute and a vow of silence. Should the publisher change its mind—or wish to renegotiate feudal terms—it can order the library to delete hundreds of thousands of titles faster than you can say “Sheriff of Nottingham.”

This is not an accident. It is the business model.

The New Lords of the Realm

In medieval Europe, five or six noble houses controlled nearly everything. In modern scholarly publishing, the number is roughly the same. These publishers produce no crops, dig no canals, and write none of the research they sell. Instead, they rely on a marvelously efficient formula: let the public pay professors to create knowledge, let the professors hand over their work for free, then charge the public’s universities millions to lease it back.

It is, as TEDx speaker Jeffrey Edmunds notes with admirable understatement, “economically nonsensical.” But so was the Holy Roman Empire, and that lasted almost a thousand years.

To ensure the peas—pardon me, readers—don’t compare notes, publishers require every library to sign nondisclosure agreements forbidding any mention of what things cost. One imagines a medieval scribe whispering, I’d tell you what we paid for the new Psalter, but the abbot swore me to secrecy.

Meanwhile, in the Kingdom of Amazonia…

If publishers are the new barons, Amazon is the Archbishop of Everything. As of February 2025, Kindle owners are no longer be permitted to back up their legally purchased ebooks anywhere except a Wi-Fi-enabled Kindle device. Your library will henceforth live exclusively inside the company’s cathedral, subject to the indulgences and excommunications of its high priests.

Lose your account? Violate a term of service you didn’t know existed? Offend the wrong algorithm? Poof—your books vanish as cleanly as the Library of Alexandria, except without the helpful historical footnote.

And if Amazon or a publisher decides that a particular edition needs “corrections,” the text can be silently rewritten while you sleep. One morning you wake up and Winston Smith is the hero. The next morning he’s the villain. By Thursday the whole story has been replaced with recipes using plant-based cheese.

Readers with long memories will recall that Amazon once deleted 1984 and Animal Farm from Kindles due to a copyright squabble, thus producing the only moment in human history when George Orwell became a breaking news story.

The Kindle Price Conspiracy: Or, How to Pay More for Less

You might assume the privilege of owning nothing would at least come with a bargain price. Alas, the opposite is true. As Michaela of whatmichaelareads explains, new Kindle releases often cost more than hardcover editions. This is because publishers desperately want physical copies to sell—those are what count for bestseller lists, which are still compiled as though the internet never happened.

Thus the industry keeps ebook prices artificially high, not because electrons are expensive, but because charts are sentimental. It’s as if Netflix charged $29.99 to stream a movie in order to protect your local Blockbuster.

If this feels like readers are being penalized to subsidize a retail model they don’t use—well, as we say in Beaver County, that’s because they are.

The Renaissance We Actually Need

Edmunds is right: knowledge is a public good, more akin to electricity than jewelry. It is funded collectively, created collectively, and democracy depends on all of us having access to it. When half of Penn State students skip buying textbooks because prices have risen 1,000% in 40 years, we are not building an educated republic. We are reenacting the Dark Ages, when literacy was a luxury item and the price of a good Bible could rival the GDP of Switzerland.

Fortunately, alternatives exist. The editors of lingua walked out of Elsevier and founded glossa, a free, open-access journal of equal quality and infinitely better principle. Open Educational Resources offer free textbooks that professors can adapt without paying tribute to a publishing house. Libraries—those stubborn fortresses of the common good—are fighting to preserve real ownership, real access, and real archives.

It’s a long road back from the digital serfdom we’ve drifted into, but there’s precedent. After all, Europe eventually emerged from the medieval period. A few open-access journals, some honest pricing metrics, and a dash of reader rebellion may yet get us there faster than the monks did.

In the meantime, if you want to make sure your grandchildren can still read your favorite books, buy a print copy. Put it on a shelf. Write your name in it, the way your grandparents did. Hand it down like an inheritance.

You may not own your ebooks. But you can still own your books.