By Hugh A. Brackenridge

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

[This essay first appeared in The Editor & Publisher, vol. 13, no. 18, October 1913. Hugh A. Brackenridge was a descendent of Hugh Henry Brackenridge (1748–1816), founder of The Pittsburgh Gazette, the first newspaper West of the Alleghenies.]

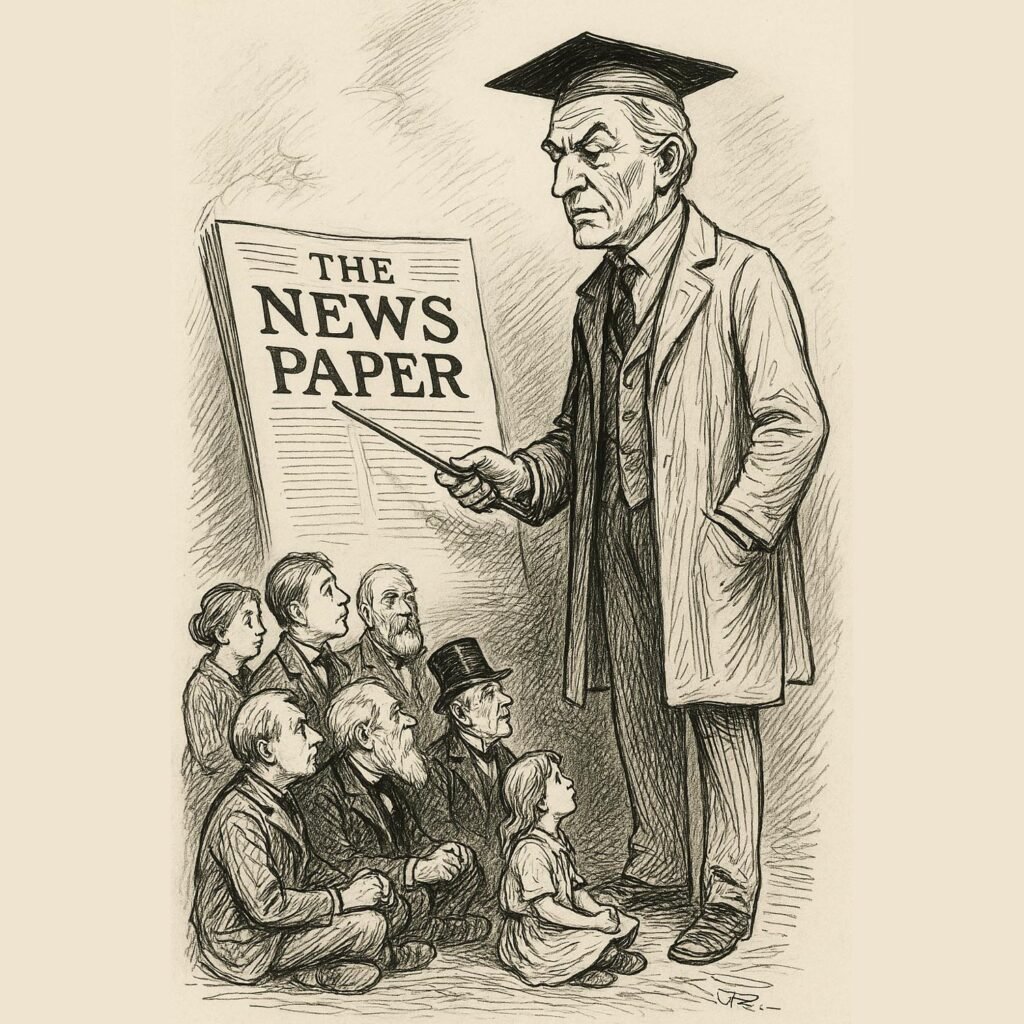

The newspaper is the most universal and the most democratic of all agencies of education. It touches more lives daily than all the schools, colleges, and churches of the land combined. It reaches the rich and the poor, the old and the young, the learned and the ignorant. It educates while it entertains. The reader is often unconscious that he is being taught, but the lesson sinks in just the same.

It is the greatest single civilizing influence in modern life. It spreads knowledge, ideas, standards of conduct. It raises the level of the community, often without the community’s knowing just how it is done. It is the quiet, steady force that makes for better citizenship, better morals, better manners.

The newspaper creates public opinion. It does not merely reflect it. It determines what the public shall think about. It selects the topics of conversation, the subjects of debate. Without the newspaper, there would be no public opinion worthy of the name, for there would be no common ground of discussion.

It is the daily textbook of democracy. It teaches the citizen his rights and duties, his opportunities and responsibilities. It keeps him in touch with the government, with the world. It makes self-government possible by making self-instruction possible. A nation of newspaper readers is a nation of informed voters.

Its influence is subconscious and cumulative. The reader does not remember the particular article that impressed him today. He does not recall the paragraph that changed his point of view tomorrow. But day after day, month after month, year after year, the ideas sink in. The newspaper is the most persistent of teachers, the most intimate of companions.

It is indispensable to progress. Commerce depends upon it for markets, invention for recognition, reform for propaganda. Every forward step in civilization—every new machine, every social betterment, every political advance—owes its rapid spread to the newspaper. Without it, the world would stagnate.

Its value is beyond all price. For a few cents a day a man gets what has cost hundreds of workers, millions of capital, and the combined brains and energy of a great organization to produce. No man could gather for himself, at a thousand dollars a year, a tithe of what the newspaper brings to his door. It is the cheapest of luxuries, the most necessary of necessities.

No other agency touches so many minds so constantly, so intimately, and so cheaply. That is the real value of a newspaper.

[This essay first appeared in The Editor & Publisher, vol. 13, no. 18, October 1913. Hugh A. Brackenridge was a descendent of Hugh Henry Brackenridge (1748–1816), founder of The Pittsburgh Gazette, the first newspaper West of the Alleghenies.]

The newspaper is the most universal and the most democratic of all agencies of education. It touches more lives daily than all the schools, colleges, and churches of the land combined. It reaches the rich and the poor, the old and the young, the learned and the ignorant. It educates while it entertains. The reader is often unconscious that he is being taught, but the lesson sinks in just the same.

It is the greatest single civilizing influence in modern life. It spreads knowledge, ideas, standards of conduct. It raises the level of the community, often without the community’s knowing just how it is done. It is the quiet, steady force that makes for better citizenship, better morals, better manners.

The newspaper creates public opinion. It does not merely reflect it. It determines what the public shall think about. It selects the topics of conversation, the subjects of debate. Without the newspaper, there would be no public opinion worthy of the name, for there would be no common ground of discussion.

It is the daily textbook of democracy. It teaches the citizen his rights and duties, his opportunities and responsibilities. It keeps him in touch with the government, with the world. It makes self-government possible by making self-instruction possible. A nation of newspaper readers is a nation of informed voters.

Its influence is subconscious and cumulative. The reader does not remember the particular article that impressed him today. He does not recall the paragraph that changed his point of view tomorrow. But day after day, month after month, year after year, the ideas sink in. The newspaper is the most persistent of teachers, the most intimate of companions.

It is indispensable to progress. Commerce depends upon it for markets, invention for recognition, reform for propaganda. Every forward step in civilization—every new machine, every social betterment, every political advance—owes its rapid spread to the newspaper. Without it, the world would stagnate.

Its value is beyond all price. For a few cents a day a man gets what has cost hundreds of workers, millions of capital, and the combined brains and energy of a great organization to produce. No man could gather for himself, at a thousand dollars a year, a tithe of what the newspaper brings to his door. It is the cheapest of luxuries, the most necessary of necessities.

No other agency touches so many minds so constantly, so intimately, and so cheaply. That is the real value of a newspaper.