By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher, Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

In the long, slow parade of America’s self-inflicted wounds, none has been quite so elegant—or so cheerfully destructive—as our decision, over the past fifty years, to trade in factories, foundries, and know-how for the economic mirage of “financial efficiency.” It’s a bit like selling the family farm to buy an autonomous riding mower: sleek, modern, and completely useless once the land is gone.

Craig Tindale, an Australian financier who recently laid out this argument in an essay on X, did not have Beaver County specifically in mind. But he might as well have been standing on the old J&L mill site in Aliquippa, hands in pockets, saying: “Here’s Exhibit A.”

His point, roughly translated: The West spent decades outsourcing the messy business of making things—steel, aluminum, chemicals, the humble guts of everyday life—to far-off places willing to handle fire, noise, and payrolls. We, meanwhile, devoted ourselves to the loftier pursuit of squeezing costs out of balance sheets, as though the national goal were to run the country like a hedge fund.

It worked beautifully, until it didn’t.

The Cult of Efficiency

By the late 1990s, phrases like “cost optimization,” “lean operations,” and the truly gorgeous “asset-light strategy” were floating through corporate earnings calls the way cigarette smoke used to billow across Beaver Falls diners at the breakfast shift. Anything that could be moved overseas was. Anything that couldn’t be moved overseas was politely shown the door.

In finance, this made perfect sense. In national life, it was lunacy.

But let’s be charitable. It’s hard to pass up cheap labor, hard to resist the spreadsheet’s sweet siren song. And for a time, the whole system hummed. Goods got cheaper. Stock prices got happier. Consumers got televisions so large they now require municipal zoning exemptions.

The only losers, as it turned out, were the people who built things—and the communities that depended on them.

Beaver County: The Case Study Nobody Asked For

Drive past the riverfronts of Aliquippa, Beaver Falls, or Monaca, and you still see the ghostly footprints of what once made the West materially independent. Blast furnaces, rolling mills, tanneries, glass factories—everything that gave Beaver County its purpose, its smell, and, depending on the day, its temperament.

We exported steel. We imported nothing except the occasional Cleveland Browns fan who had taken a wrong turn.

Then globalization arrived, and the old industrial DNA began unraveling like a Steelers secondary in the fourth quarter.

We didn’t lose capability all at once. It leaked away, one contract, one shuttered machine shop at a time, until America woke up one morning unable to manufacture half the essentials required for its own prosperity. Batteries. Solar panels. Rare-earth magnets. Microchips. Pathways to prosperity recast as overseas line items.

And yet, in the financial world, all of this was considered progress. Every mill closed represented cost savings. Every operation shifted abroad counted as improved margins. Wall Street applauded; Aliquippa wept.

Material Sovereignty: A Fancy Term for “Do We Still Know How to Make Stuff?”

Tindale calls it a loss of “material sovereignty,” a phrase that sounds as though it should be delivered from a mountaintop by a bearded prophet but simply means this: Can a nation supply itself with the things it needs to function?

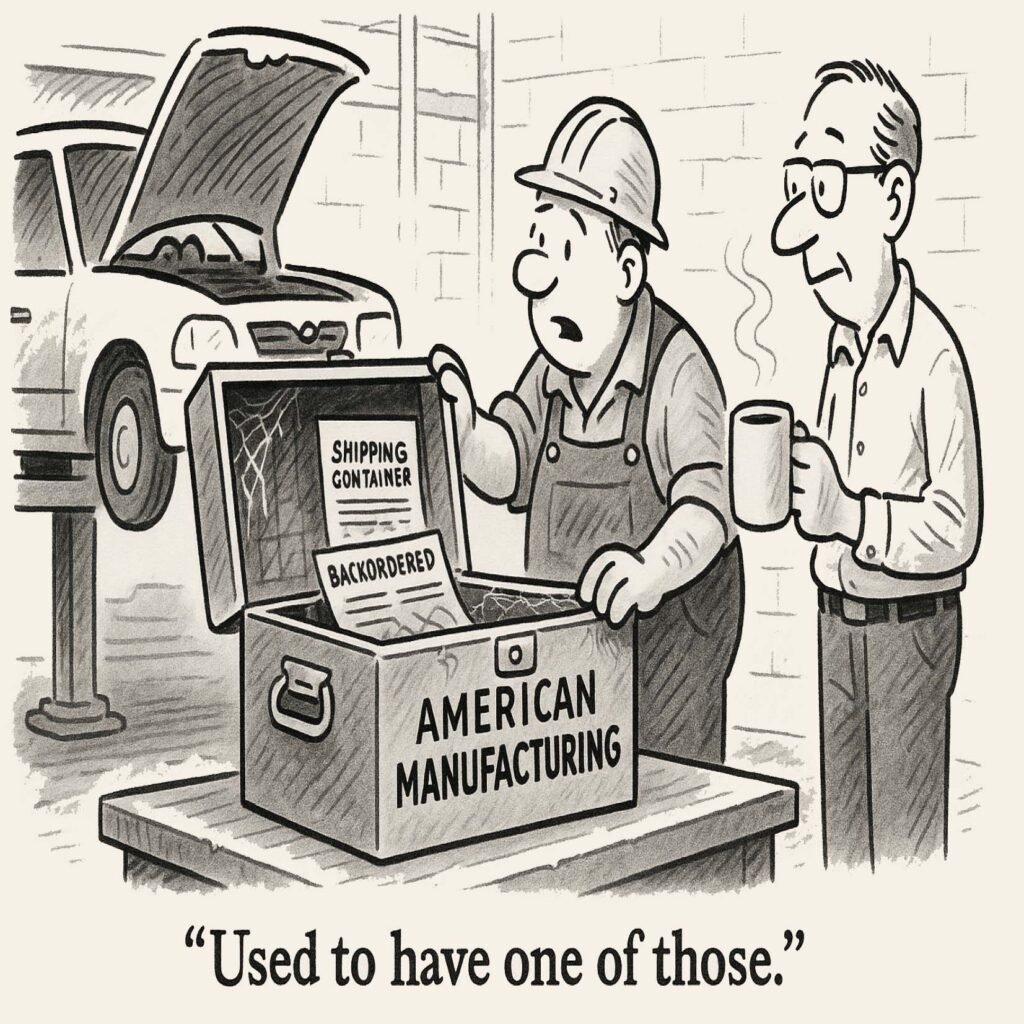

In America’s case, the answer is now: “Sometimes, if the shipping container arrives on time.”

We are not fully dependent, not yet. But we’ve gotten into the troubling habit of trusting geopolitical stability—an oxymoron if ever there was one—to keep our shelves stocked and our supply chains humming.

If you doubt this, ask anyone at the cracker plant in Potter Township how many supply-chain crises they’ve had to stare down in recent years. Or ask your local auto mechanic how many weeks it now takes to get a replacement part that used to be sitting on a shelf in Rochester.

The odd part is that the people who lost the most—places like Beaver County—may now stand to gain the most.

The Unlikely Comeback of Making Things

As the world rediscovers the importance of manufacturing (usually after realizing the country that makes all your stuff can also turn off the tap), industries are tiptoeing back. Chip fabs. Battery plants. Specialty metals. Logistics hubs. Suddenly, the ability to make things is being treated with the reverence once reserved for bond ratings.

And Beaver County, with its industrial bones and a work ethic that still remembers shift whistles, looks suspiciously well-positioned.

This does not mean the glory days of 20,000-worker mills will return. They won’t. Today’s industrial facilities employ more robots than people—and the robots tend not to buy sandwiches at the Brighton Hot Dog Shoppe.

But the tide may be turning. Slowly. Quietly. With fewer sparks and more semiconductors.

The Lesson for Our County

The real point of Tindale’s argument isn’t that China is clever or that America is foolish. It’s that a society ultimately becomes what it chooses to value.

Beaver County once valued production—heat, labor, pride. Then the nation chose to value efficiency, returns, and the mystical art of turning industrial towns into logistics corridors. Now, perhaps, we are wobbling back toward valuing capability itself.

We should welcome it.

Because a county that knows how to make things is a county with a future. A county that relies on container ships and good fortune is a county waiting to be disappointed.

And, as we’ve learned over the years, Beaver County has experienced quite enough disappointment to last several lifetimes.