By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher, Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

It is a truth universally acknowledged—at least in Western Pennsylvania—that if a famous writer once passed within shouting distance of a river confluence, he is thereafter rumored to have slept in Beaver County, eaten pierogies in Aliquippa, and penned his masterpiece somewhere near the courthouse. This is not true of Charles Dickens, any more than it is true of Washington Irving. Neither man ever visited Beaver County. But both, in their different ways, helped invent the Christmas we still argue over, celebrate, and occasionally endure.

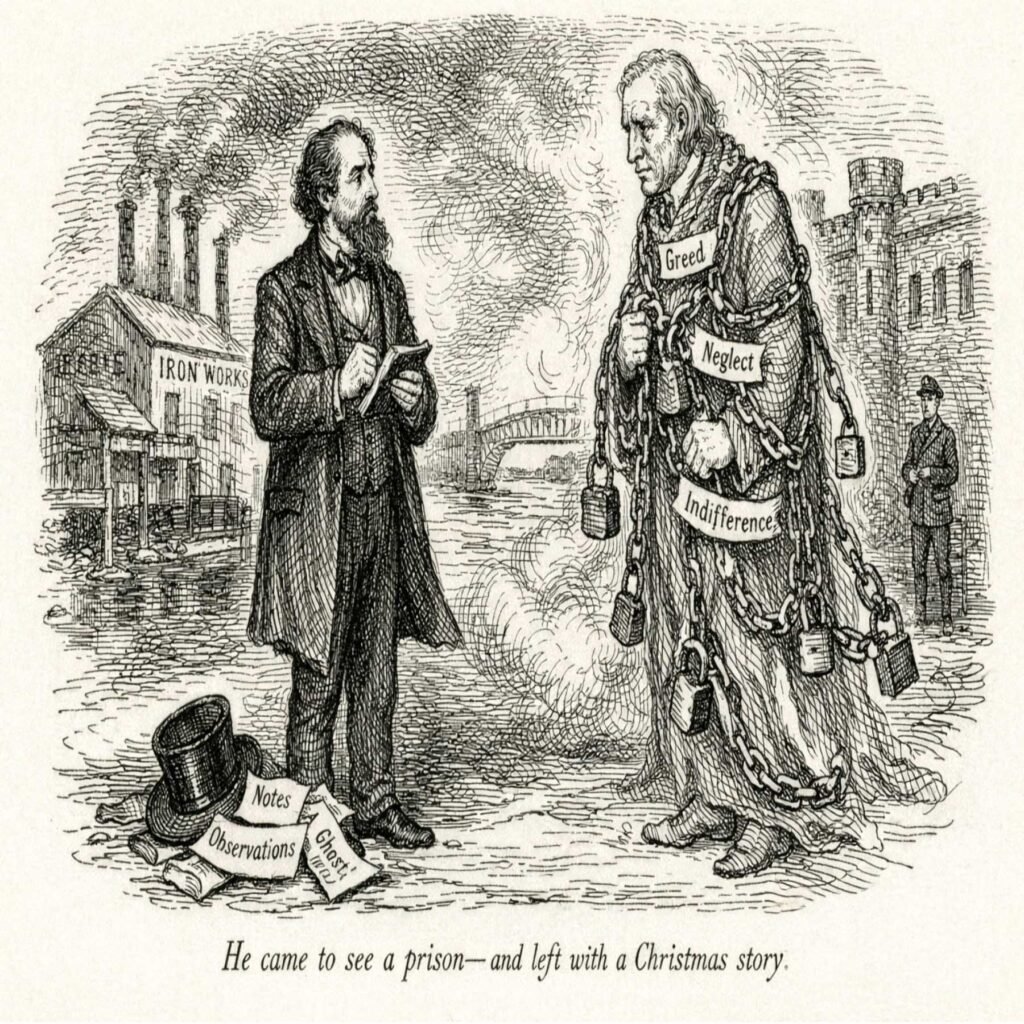

Dickens did, however, come tantalizingly close. In March 1842, during his whirlwind American tour, he spent three days in Pittsburgh—long enough to admire the scenery, praise the hotel, inhale several tons of coal smoke, and carry away an image that would haunt him straight into literary immortality.

He arrived by aqueduct, which he found dreamlike in the way only a long wooden box full of river water can be, and emerged into what he memorably called an “ugly confusion of backs of buildings and crazy galleries and stairs.” This, he noted with the weary air of a man who had seen too many waterfronts, was what always happened when cities met water.

Pittsburgh, to Dickens, was “very beautifully situated” and also smothered in smoke—two observations that have remained simultaneously true for much of its history.

He compared the place to Birmingham, England, a city famous for ironworks, industry, and the sort of soot that gets into your soul and refuses to come out. Pittsburgh’s townspeople, he added archly, were the ones who made the comparison. Dickens merely confirmed it.

Contrary to popular belief, he never called the city “hell with the lid taken off.” That honor belongs to James Parton, writing a quarter-century later, when the furnaces were even hotter and the night sky glowed like the Book of Revelation. Dickens was subtler. He simply let the smoke do the talking.

Socially, he was well treated. The hotel—likely the Exchange—was excellent. The table was admirably served. He dined with pleasant company. But the city itself did not enchant him. Compared with Boston, which he found clean and civilized, Pittsburgh struck him as raw, noisy, and prematurely aged by industry.

What truly stayed with him, though, was not the smoke but the chains.

During his stay, Dickens toured the Western Penitentiary, then one of the nation’s modern experiments in incarceration. He was already deeply troubled by prison systems, having visited Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia and condemned solitary confinement as a slow torture of the mind. In Pittsburgh, he saw prisoners in irons—literal chains, heavy and inescapable. The image lodged itself where Dickens kept his most dangerous ideas.

A year and a half later, when he sat down to write A Christmas Carol, those chains came back, transformed. Jacob Marley appears dragging the iron he forged in life, “link by link, and yard by yard,” a walking sermon on moral accounting. Without Marley—without the shock of that apparition—the story collapses. No ghost, no warning; no warning, no redemption. It is not too much to say that a prison tour in Pittsburgh helped give Christmas its most famous ghost.

Dickens did not invent the holiday from scratch. Like Irving before him, he drew from older traditions—fireside gatherings, feasts, music, a sense that winter was survivable if people were kind to one another. Irving’s Christmas sketches, set at Bracebridge Hall, revived a nostalgic English Yuletide and deeply influenced Dickens, who once confessed he rarely went to bed without Irving tucked under his arm. Dickens took that old-fashioned warmth and dropped it into industrial London, where the poor froze in the shadows of wealth.

The result was revolutionary. A Christmas Carol redefined the “true meaning of Christmas” not as doctrine or discipline, but as behavior: kindness, generosity, attention to family—especially the improvised kind made up of neighbors, clerks, nephews, and the occasionally inconvenient poor. Christmas, in Dickens’s telling, became a season for noticing other people.

Nearly two centuries later, the book refuses to age. It survives endless stage productions, film adaptations, puppets, cartoons, and at least one version involving Muppets who understand the moral arc better than most adults. The details change; the message does not. Wealth without mercy is poverty. Isolation is the coldest room of all. And it is never too late—until it is.

Dickens never crossed the Beaver River. He never saw our mills or our main streets or our churches lit up on Christmas Eve. But he understood industrial places, their damage, and their dignity. He understood that progress without compassion leaves people in chains, visible or otherwise. And he understood that Christmas, at its best, is not about what we consume, but about what we release—old grudges, old fears, old indifference.

That is a lesson worth carrying home, even through the smoke.