By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher, Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

Christmas arrives every year the same way a well-meaning relative does: full of good intentions, carrying too many packages, and staying just long enough that by January 2 we’re quietly grateful for the silence.

This is not a complaint. It is a confession of gratitude.

Because Christmas, for all its excesses, is one of the few remaining things in American life that still insists—quite stubbornly—that we pause. It interrupts commerce even as it fuels it. It demands family gatherings even from people who would prefer to communicate exclusively by text message. It forces us to confront generosity, nostalgia, forgiveness, and baked goods all at once, when the days are shortest and patience is thinnest.

At its theological core, Christmas commemorates the birth of Jesus Christ, an event described with remarkable understatement in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. No angels with scheduling software. No precise timestamp. No commemorative plaque. Just a baby born in borrowed shelter, visited by shepherds working the late shift and, eventually, by foreign dignitaries who brought gifts that were thoughtful but wildly impractical for a young family on the move.

The Bible, notably, never tells us the date. Scholars have long suspected the birth happened in spring or fall—shepherds tending flocks outdoors being a clue.

December 25 came later, several centuries later, when church leaders settled on a date that already carried cultural weight in the Roman world. The winter solstice had just passed. The days were inching longer. Light was beginning its slow comeback tour.

Some historians argue the date was chosen to Christianize pagan festivals like Saturnalia or the celebration of the “Unconquered Sun.” Others insist it followed a theological calendar that placed Christ’s conception on March 25, with birth nine months later. Both explanations have merit, and neither has ever been successfully debated into submission at a parish Christmas dinner, which tells you something about the endurance of mystery.

What matters is that December 25 stuck—and once it did, Christmas began to accumulate traditions the way a snowball accumulates slush rolling downhill on Third Street in Beaver.

Gift-giving traces its lineage to the Magi—gold, frankincense, and myrrh—an early reminder that Christmas presents were never meant to be easy to assemble or explain to a child. Medieval Europe layered on charity and ceremony. Kings were crowned on Christmas Day. Time itself was reordered around the event, dividing history into before and after. Not bad for a child born without a permanent address.

Then there was Saint Nicholas, a fourth-century bishop from what is now Turkey, whose reputation for anonymous generosity earned him sainthood and, eventually, a second career in retail logistics. The most enduring legend has him secretly providing dowries for impoverished sisters by tossing bags of gold through a window—or down a chimney—where the coins landed in stockings drying by the fire.

This story alone has justified centuries of parental negotiations.

Christmas trees followed a similar path. Evergreens had symbolized life in winter long before Christianity, but medieval “paradise plays” brought them indoors, decorated with apples to represent the Garden of Eden. German families later added candles. A charming legend credits Martin Luther with the innovation, inspired by starlight shining through branches. Whether or not Luther was involved, the idea took hold: light in darkness, life in cold, beauty where it seems least practical.

Anyone who has survived a Beaver County January understands this instinct perfectly.

America, of course, could not leave these traditions alone. Immigrants arrived with their own versions of Christmas, and the country blended them into something louder, warmer, and more entrepreneurial. Dutch settlers brought Sinterklaas. Writers reshaped him. In 1823, Clement Clarke Moore published “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” giving us reindeer, chimneys, and a Santa who could get in and out of a house faster than a lineman responding to a Christmas Eve power outage.

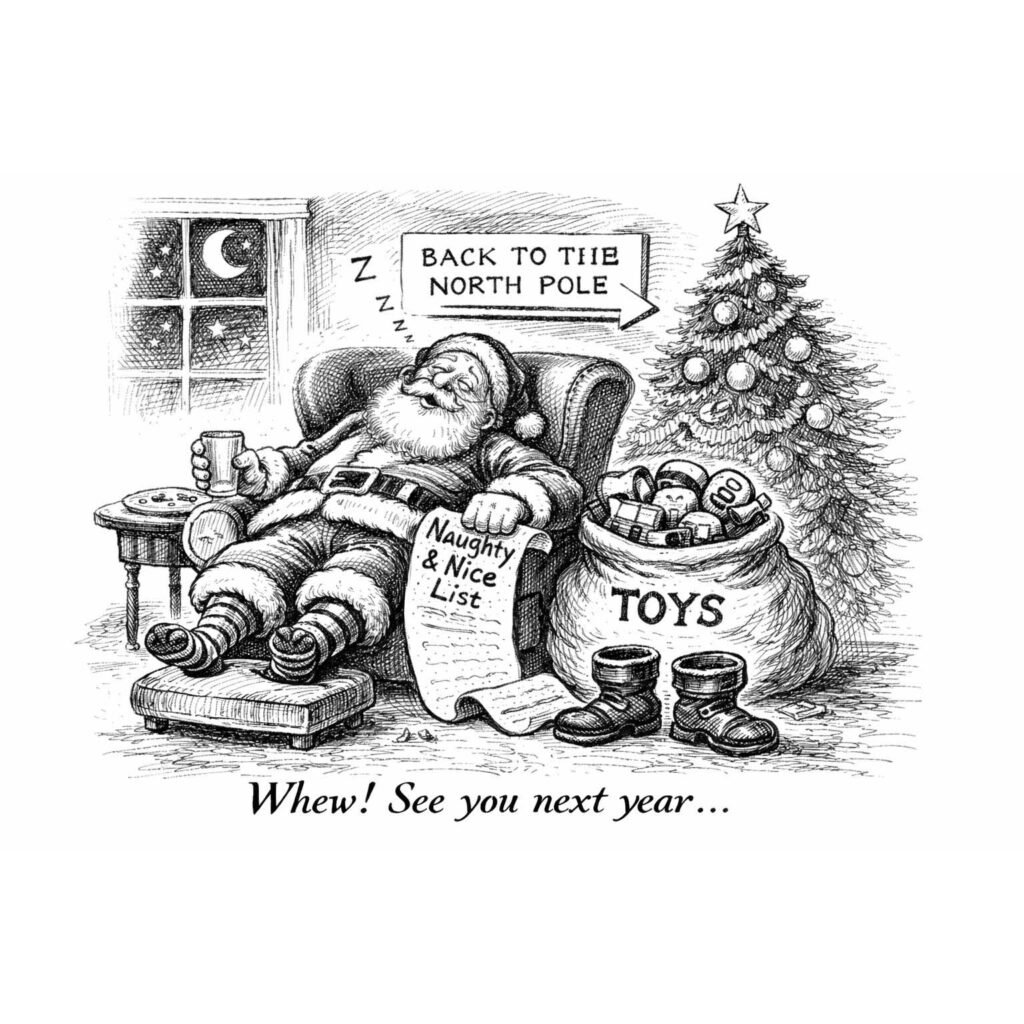

Then came Dickens, reminding a soot-covered industrial world that redemption was possible, even for employers. Cartoonists put Santa in a red suit and stationed him at the North Pole, where he could be safely mythologized. By the 20th century, advertising gave Santa a face recognized from Beaver Falls to Beijing.

Along the way, Christmas absorbed contradictions with admirable grace. A Jewish songwriter wrote “White Christmas,” the bestselling song in history. Puritans banned Christmas altogether for being too rowdy and insufficiently biblical, preferring sober obedience to joy. Retailers turned it into the most important economic quarter of the year, with Americans now spending north of a trillion dollars annually between Thanksgiving and New Year’s.

Critics have complained about commercialization for as long as there has been commerce. But Christmas has always lived at the intersection of the sacred and the ordinary—church and marketplace, manger and main street. The danger lies not in buying too much, but in forgetting why generosity mattered in the first place.

In Beaver County, Christmas has always been a local affair layered atop the global one. It is lights strung slightly crooked on porches in Rochester and Brighton Township. It is church basements smelling of coffee, cookies, and folding chairs that have outlived several pastors. It is downtown Beaver shop windows glowing against the early dark, and small businesses hoping—quietly, fervently—that December will carry them into January.

It is also weather watched with unusual seriousness. Snow changes plans. Ice rearranges schedules. Hills become negotiations. Families calculate routes the way generals once planned campaigns. Christmas, here, has always involved logistics.

And yet it endures.

Yes, Christmas is exhausting. It strains budgets, schedules, nerves, and waistlines. It resurrects old memories and unresolved conversations. It requires effort at a time of year when effort feels scarce.

But Christmas also insists—once a year, whether we feel like it or not—that kindness is still possible. That community is not a theory but a practice. That light returns. That generosity, however imperfectly executed, remains worth attempting.

Which brings us back to the blessing.

Christmas comes but once a year, mercifully. Any ritual this intense needs time to fade before it can be welcomed again. By January, the decorations will come down. The credit-card statements will arrive. The days will grow longer. And the world will return to its usual arguments.

Somewhere quietly, though, the next Christmas will already be forming—patient, persistent, borrowing whatever it needs to remind us, once again, who we are in God’s grand scheme of things.

And for that, we can be grateful.