By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher, Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

There was a time—recent enough to remember, distant enough to feel quaint—when conviviality did not require an app, a policy memo, or a strategic plan. You encountered it accidentally: leaning on the bar at Brady’s Run Inn, lingering too long after a football game, or getting stuck behind a shopping cart at the Beaver Valley Mall and discovering, twenty minutes later, that you knew far more about a stranger’s family tree than you ever intended.

Then, slowly, we began to lose the knack.

Long before anyone heard of COVID-19, we were already rehearsing for solitude. Front porches went decorative. Clubs and churches thinned. Friendship was rebranded as “networking,” community as “engagement,” and loneliness as a personal problem best addressed with therapy, hobbies, or a better streaming package.

When the pandemic arrived, it did not invent isolation. It perfected it.

Lockdowns—however well-intended—delivered a final blow to a social order already wobbling. We were told to keep our distance. We were also told, even more harmfully, that distance was neutral—that we could pause human proximity and resume it later, like a Netflix series.

But conviviality is not a switch. It’s a muscle. And muscles atrophy.

As British sociologist Alison Hulme observes, COVID played out against an already acknowledged “pandemic of loneliness,” rooted not simply in bad habits or screen addiction, but in the long arc of industrial capitalism itself. The promise of cosmopolitan abundance—more choice, more mobility, more efficiency—did not, for many people, deliver belonging. Instead, it produced enclaves and silos, open plans that somehow felt closed, and lives organized expertly around everything except one another.

To understand what we lost, we need an older idea of friendship. Not the modern notion of finding one’s soulmate or joining a “consumer tribe,” but something closer to what the Stoics meant: mutual reliance, civic responsibility, and shared life among people who did not necessarily agree, resemble one another, or shop at the same stores.

In that older sense, conviviality was not about affinity. It was about proximity. Not about finding your people, but about learning to live with them.

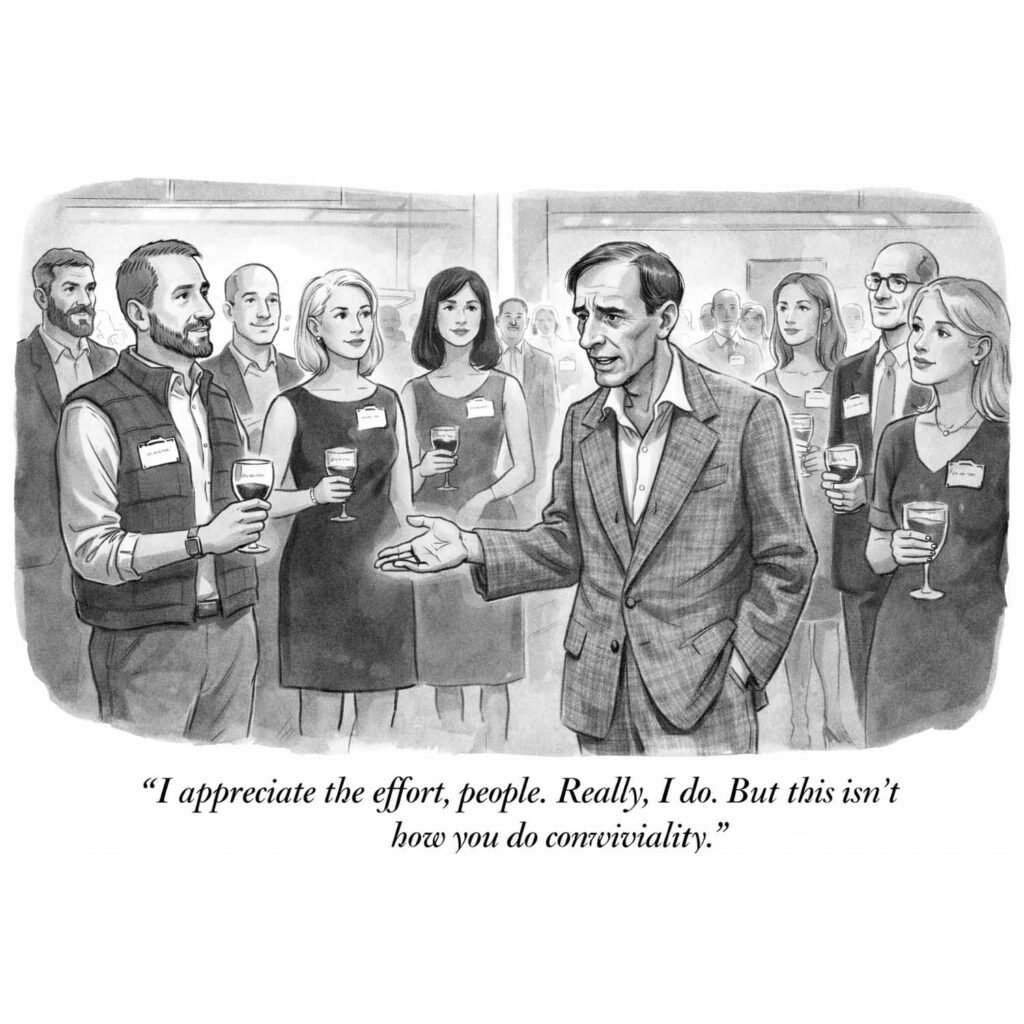

This is where Ivan Illich enters the room, clears his throat, and makes everyone uncomfortable—wearing, as it were, a leisure suit and the grim expression of a man who knows the party cannot last.

In Tools for Conviviality (1973)—published at the height of polyester optimism and just as faith in institutions was beginning to fray—Illich argued that modern “tools” had exceeded their useful limits. By tools, he meant not just machines, but institutions: schools, hospitals, transportation systems, professional bureaucracies. They pass what he called a “second watershed,” beyond which they stop serving human needs and begin frustrating them.

Conviviality, Illich wrote, is “autonomous and creative intercourse among persons, and the intercourse of persons with their environment.” In plain English: people doing things together, using tools they understand and control, without being managed to death by experts.

A hammer is convivial. Anyone can use it. A bicycle, too. A system that requires credentials, compliance officers, dashboards, and disclaimers to perform the basic tasks of living is not.

Industrial society promises liberation and delivers dependence. The faster the car, the more time you spend in traffic. The more specialized the professional, the less confident you feel doing anything yourself. Eventually, one system crowds out all alternatives—a condition Illich memorably called “radical monopoly.” When driving becomes mandatory and walking becomes dangerous, you are not free.

The pandemic exposed how complete that monopoly had become. When institutions shut down, many of us discovered we no longer knew how to improvise community. We waited for guidance. We substituted screens for presence. We learned, to our surprise, that “staying connected” was not the same thing as being together.

Illich would not have been surprised.

He argued that resilience depends on convivial relationships that can turn the “stranger in our midst” into a plausible collaborator. Not a soulmate. A neighbor. Someone with whom you might organize a food drive, clear debris after a storm, or check in when things go sideways.

Instead, we outsourced resilience to systems designed for efficiency, not care. And when those systems faltered, there was very little left underneath.

Illich’s remedy was “convivial reconstruction”: redesigning society’s tools so they enhance interdependence rather than erode it. This did not mean rejecting technology. It meant setting limits—real limits—on scale, speed, and compulsory change.

A convivial society values participation over consumption, judgment over credentials, sufficiency over endless growth. It treats limits not as deprivation, but as discipline—the kind that keeps tools useful and life human.

The pandemic did real damage in Beaver County, not just economically, but socially. Habits were broken. Trust thinned. A generation learned that other people were, first and foremost, a risk. Rebuilding conviviality will require more than grants, slogans, and ribbon cuttings. It will require spaces that invite lingering, institutions that tolerate imperfection, and tools people can actually use without asking permission.

Conviviality grows sideways, not upward. It cannot be scaled, optimized, or monetized without ceasing to be itself.

The next time the power goes out, the system crashes, or the experts disagree, the most valuable tool you will have will not be an app or a dashboard.

It will be the person who brings over a flashlight, knows which breaker to jiggle, and remembers how your parents took their coffee.

Around here, that used to be called a neighbor.