By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher, Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

There are two kinds of financial crises. The first arrives with sirens blazing—ticker tape screaming red, cable news anchors sweating through their makeup. The second arrives quietly, like a man repossessing your car at 5:12 a.m. while you’re still arguing with the alarm clock.

If you listen closely, you can hear the second kind idling outside.

According to the more financially savvy corners of the internet—and, increasingly, to people who normally prefer their daily drama limited to PennDOT detours—we’re living through the final quiet moments of the old financial world. On January 1, 2026, a series of geopolitical and structural “kill switches” are set to activate at once. Not a correction. Not a recession. Something more like a plumbing failure in a skyscraper built on decades-old assumptions.

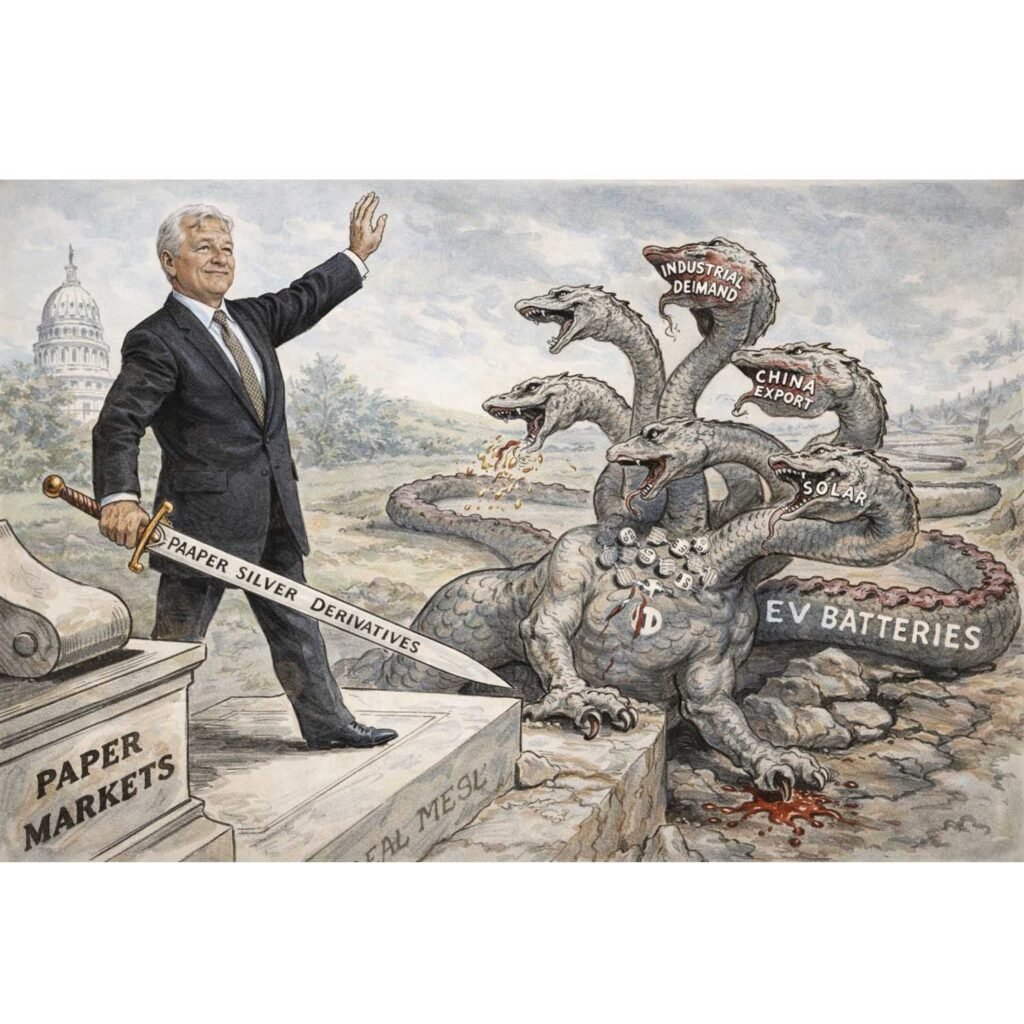

At the center of the story sits JPMorgan Chase, the largest bank in the United States and, for decades, the undisputed king of precious metals trading. JPMorgan is allegedly sitting on a massive short position in silver—bets that silver prices would fall—estimated around $22 billion. That’s not an investment strategy so much as a physics problem: they have promised to deliver far more silver than may exist in deliverable form.

This didn’t start yesterday. It goes back to 2008, when JPMorgan inherited Bear Stearns’ silver mess during the financial crisis. Instead of cleaning it up, the bank learned to live with it—using futures markets, algorithms, and a practice later described by the Justice Department as criminal spoofing to keep silver prices politely subdued. In 2020, regulators fined JPMorgan $920 million. On Wall Street, that’s not a punishment; it’s a rounding error.

What changed isn’t morality. It’s math.

Silver has quietly stopped being a quaint precious metal and become an industrial choke point. The big shock came in 2025 when Samsung SDI unveiled a solid-state electric vehicle battery that charges in minutes, runs hundreds of miles, and—here’s the rub—uses large amounts of silver in its anode. Not graphite. Not copper. Silver. Estimates suggest up to a kilogram per vehicle.

Add to that a solar industry shifting to more efficient cells that use more silver, not less, and you have demand that is mathematically inelastic. If you’re building a battery or a solar panel, you don’t get to substitute aluminum or copper and hope for the best. Without silver, your $40,000 car or $400 panel becomes a decorative object.

Meanwhile, supply is getting strangled.

On January 1, China will implement a new export licensing regime that effectively treats silver as a strategic national asset. This isn’t a tariff. It’s a switch. Beijing can approve or deny exports at will. Given that China dominates silver refining and also dominates EVs and solar manufacturing, the incentives are obvious. Starve competitors. Feed your own factories.

At the same moment, the London Bullion Market Association plans to enforce a technical “good delivery” rule that could render hundreds of millions of ounces of perfectly fine silver—much of it stamped with Cyrillic characters—non-deliverable for futures settlement. The bars don’t disappear. They just become unusable in the paper markets that depend on them.

So, to recap: China tightens exports. London tightens rules. Industrial demand goes vertical. And the paper market—where fifty people hold claims on every physical ounce—discovers that chairs are in short supply.

This is where Beaver County enters the picture.

You may not trade commodities futures in your spare time (though I wouldn’t judge), but you have noticed something curious: Costco selling silver bars—and selling out. Month after month. Hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth. This is not because Costco shoppers have suddenly become amateur metallurgists. It’s because regular people have discovered a timeless truth: if the screen says $35 but the coin costs $45, the price is $45.

That gap—the spread between paper price and physical price—is the canary in the coal mine. When it widens, it means confidence is leaking out of the system.

The danger for banks isn’t speculation; it’s delivery. If even a modest number of industrial buyers or large funds demand metal instead of cash, the clearinghouses get nervous. If a major short fails, the clearinghouse—think CME Group—has to pay. If losses exceed the default fund, trading freezes. The repo market seizes. Liquidity evaporates. Suddenly, your “boring” silver story is eating the financial system’s lunch.

Banks and regulators have emergency levers, of course. They can raise margin requirements to punitive levels. They can impose position limits. They can even declare “liquidation-only” trading—turning off the buy button, as we’ve seen before. None of this creates silver. It just changes who takes the loss.

There is also the military wildcard. Silver isn’t jewelry in that world; it’s bearings, contacts, radar, satellites. The U.S. stopped publicly reporting strategic silver stockpiles decades ago. If shortages become acute, the Defense Production Act doesn’t negotiate with coin shops. Civilian supply disappears.

Which again, brings us back home.

Why should Beaver County care? Because this county understands real things. Steel. Energy. Physical infrastructure. We know that you can’t 3D print a bridge or spreadsheet your way out of a missing mill.

Silver is drifting back into that category—less financial asset, more industrial necessity.

If the paper markets fracture, prices won’t politely adjust. They will be discovered—loudly—where metal actually changes hands. JPMorgan, reportedly shifting operations toward Asia, appears to understand this. They’re trying to survive a world where paper promises matter less than inventory.

January 1, 2026, may not bring fireworks. Markets will try to muddle through. But watch the premiums. Watch availability. Watch who gets metal and who gets apologies.

For forty years, silver’s price has been set by men trading paper in London and New York. In the next phase, it will be set by engineers, manufacturers, and governments that actually need the stuff. That’s not a conspiracy. It’s a supply chain.

And in Beaver County—where we’ve seen what happens when the real economy collides with financial abstraction—we might recognize the pattern before the talking heads do.