By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher, Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

Beaver County has never been shy about the art of self-reinvention. We have reinvented ourselves so many times that it has become a local tradition, like high school football, zoning disputes, and arguing about whether Bridgewater counts as Beaver. We went from river trade to railroads, from steel to silicon, from smokestacks to server racks. Every few decades someone announces, with great confidence, that this time the old identity is gone for good—only for it to reappear wearing a different hat and asking for a tax abatement.

Which is why a recent video by Chase Hughes landed with such a familiar thud. It argues—politely, scientifically, and with the unnerving calm of a man who knows where all the switches are—that neuroscience has now figured out how to remake not just economies or communities, but the thing we stubbornly believe to be untouchable: the self.

The Study

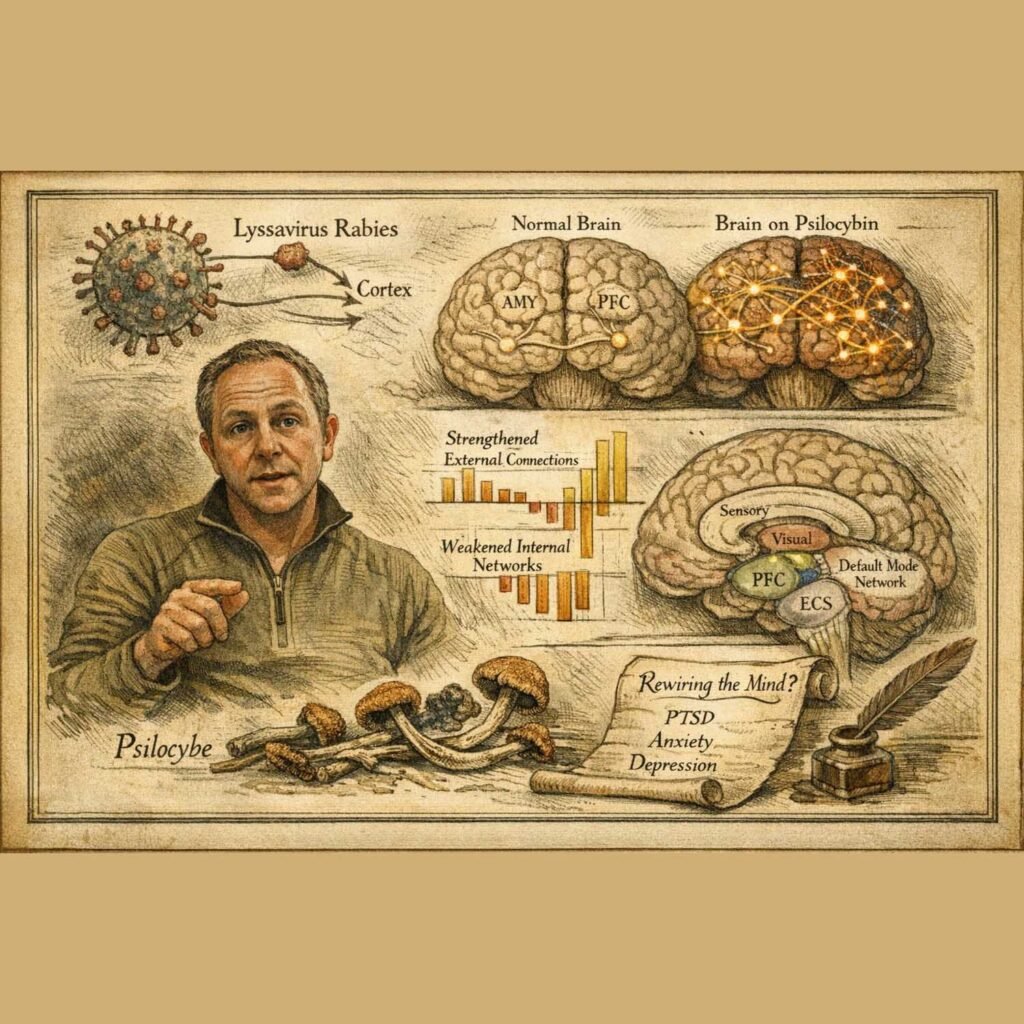

The study Hughes describes, conducted by researchers at Cornell and the Allen Institute, did something that until recently would have sounded like the plot of a late-season X-Files episode. They used a modified, non-lethal version of the rabies virus as a kind of biological highlighter. Rabies, as it turns out, is a diligent traveler: it moves backward through neural connections, neuron to neuron, tracing pathways the way a county road crew follows potholes in spring. By tagging the virus, researchers could see—live and in color—which parts of the brain were talking to which other parts.

Then they introduced psilocybin, the compound found in what polite society still insists on calling “magic mushrooms,” and watched what happened.

What Happened

What happened was not chaos. No psychedelic free-for-all. No neurological demolition derby. Instead, the brain rewired itself with all the precision of a well-run union shop.

Connections to the outside world—sensory input, vision, movement—grew stronger, by as much as ten percent. Meanwhile, the circuits responsible for our internal monologue—the anxious narrator, the fear factory, the endlessly rehearsed list of grievances—grew weaker, in some cases by fifteen percent. The default mode network, the place where we endlessly explain ourselves to ourselves, loosened its grip.

In other words, the brain did something Beaver County has done repeatedly: it stopped obsessing about what it used to be, and paid closer attention to what was right in front of it.

Attention as Destiny

The truly unsettling part comes next. Researchers discovered they could control which regions rewired. If they chemically silenced a part of the brain during the psilocybin session, that part simply sat it out. No rewiring. No makeover. The rest of the brain carried on without it.

Translation for non-neuroscientists: during these windows of heightened plasticity, attention becomes destiny. What you focus on determines which version of you walks out the other side.

The Double-Edged Sword

At this point, Beaver Countians may feel a strange mix of pride and suspicion. Pride, because we’ve been practicing this maneuver for two centuries without a lab coat. Suspicion, because any process that promises transformation this efficiently usually comes with a bill—or a sermon.

Hughes is careful to call it a double-edged sword. On one hand, the therapeutic potential is astonishing. Trauma, depression, PTSD—conditions that can dominate a person’s internal narrative for decades—may be weakened in a single session by literally loosening the neural knots that keep replaying the same story. Anyone who has watched a town struggle to move past a mill closure understands the appeal of that.

On the other hand, when a mind becomes that malleable, whoever controls the environment controls the outcome. Attention, once merely a scarce resource, becomes a lever. That should make us pause. Beaver County has lived through more than one era where powerful outsiders arrived with a confident plan to “reprogram” the place for its own good.

What makes this moment different—and more unsettling—is that the battlefield is no longer just Main Street or the riverfront. It’s the wiring behind our eyes.

Familiar Truth, New Schematics

And yet, there’s something oddly familiar here. The idea that the self is less fixed than we imagine is not new. Religion has said it. Philosophy has said it. Beaver County grandmothers have said it, usually while handing you a second helping and telling you that you’re not stuck being the person you were at sixteen.

Neuroscience has simply shown us the schematics.

Who Decides

The question, as always, is not whether we can remake ourselves, but who decides what the new version looks like. Beaver County’s history suggests a partial answer. We adapt best when the attention is our own—when the story we weaken is the one about inevitable decline, and the connections we strengthen are to the real, tangible world in front of us.

It turns out the brain, like Beaver County, was never broken. It was just waiting for us to pay attention to the right things.