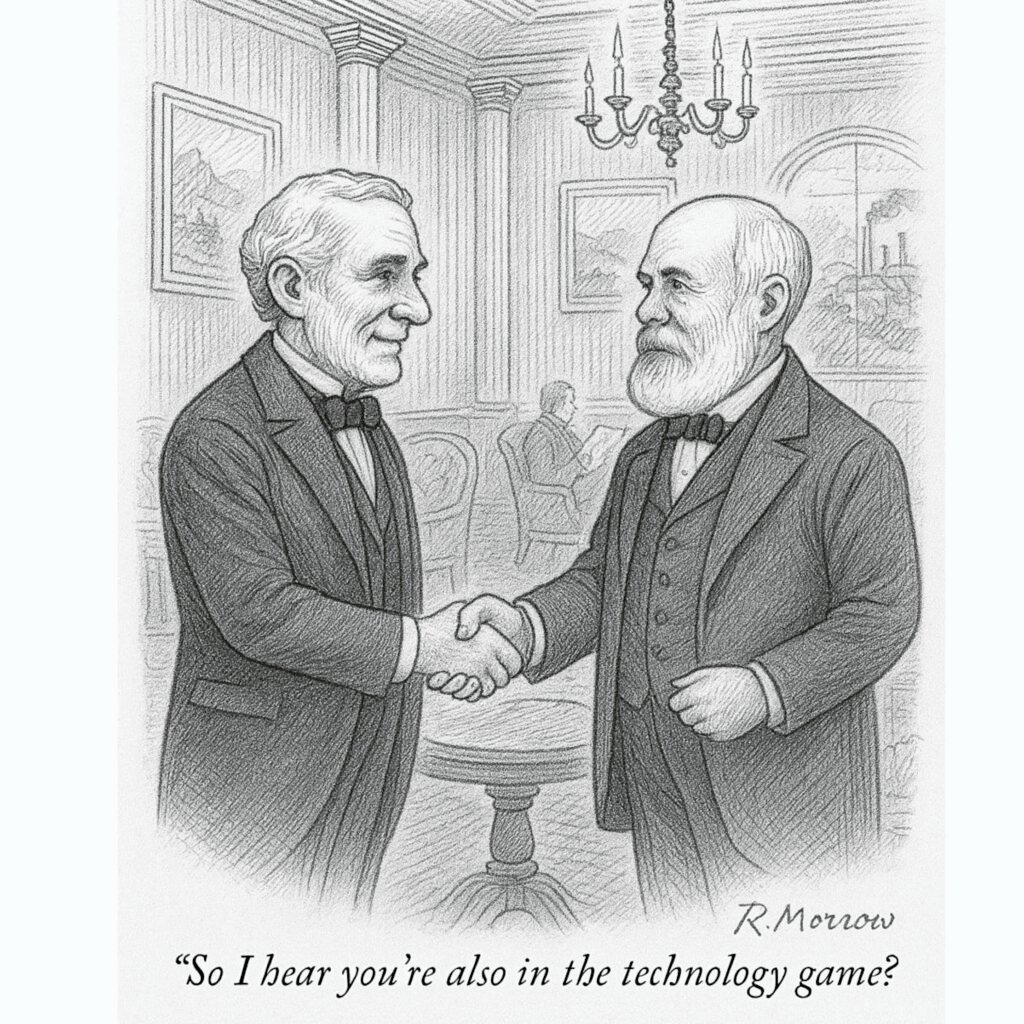

by Rodger Morrow for Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

Not since the historic day in 1854 that B. F. Jones first shook hands with J. H. Laughlin has Beaver County had reason to revive the R-word.

Back then it was an industrial landscape remade by railroads and steamships. Today the buzzwords are cryptocurrency, artificial intelligence, and nuclear power—stitched together by an economic idea once believed extinct: tariffs.

The old consensus about trade—the one that said America’s job was to keep the store open while our allies stocked the shelves—didn’t collapse with a bang so much as with the slow hiss of a blast furnace going cold. In the late 1970s, Washington embraced the Tokyo Round of the GATT, cutting industrial tariffs by about a third across advanced economies. It was great for global theory, less great for mill towns like ours.

We know how that movie ended here. In 1984, LTV—successor to Jones & Laughlin—closed most of the Aliquippa Works, tossing roughly 8,000 people out of work in one shot. The tin mill staggered along until 2000. Families moved out, storefronts emptied, tax bases shrank. The U.S. steel workforce fell off a cliff—from nearly 400,000 in 1980 to about 164,000 in 1990—as imports and overcapacity bit hard.

A new verse in Washington’s hymnbook

Half a century on, Washington’s hymn to free trade is being sung in a different key.

In April, the White House imposed a baseline 10% tariff on imports. In June it doubled Section 232 steel and aluminum tariffs to 50%. In July it extended 50% duties to semi-

finished copper and copper-intensive parts. In August, it broadened coverage to 407 finished goods ranging from transformers and HVAC systems to railcars and cranes.

Where Beaver County fits in

Some of this new scaffolding leans in our direction.

- Grid gear: Mitsubishi Electric Power Products has broken ground on an $86 million switchgear plant and testing lab in New Galilee, with ~200 jobs projected. Switchgear and breakers now sit squarely inside the tariff net, giving domestic suppliers an edge.

- Resin to reality: Shell Polymers Monaca, one of the county’s largest employers, is exploring “strategic options” for its U.S. chemical portfolio. Tariffs on finished plastics mean more room for domestic resins—like the polyethylene produced here—to move downstream.

- Steel’s flicker: 72 Steel has filed permits for an electric-arc rebar mill on the ruins of J&L.

Timelines remain fuzzy, but with imports facing a 50% wall, the math looks friendlier than it has in years.

The U.S. International Trade Commission’s own review of prior tariffs found they raised import prices, reduced volumes, and nudged U.S. production upward. That’s precisely the alchemy Beaver County entrepreneurs have been waiting for.

The fine print

Nothing is free, of course—least of all “free trade.”

Economists at the Tax Foundation estimate this year’s tariff mix costs the average household around $1,300 annually. Downstream users of imported copper and steel may feel the squeeze. The gamble is that jobs, wages, and industrial staying power will outweigh sticker shock at Lowe’s.

What’s different this time is that Beaver County has cards to play. Aliquippa’s CRONIMET now links barge, train, and truck. We’ve got grid-equipment manufacturing taking shape. We sit at the junction of energy, plastics, and metals—industries that finally look less like liabilities and more like assets.

So yes, the R-word may no longer be punchline material. The lesson of the past isn’t that tariffs are inherently good or bad, but that policy choices have consequences—and for decades, those consequences landed squarely on Aliquippa and Midland. Now the pendulum has at least swung back through our neighborhood.

Hopeful? Cautiously. Announcements are one thing; staffed shifts and paychecks are another. As my mother used to remind me when I got a little too cocksure: there’s many a slip between the cup and the lip.

But for the first time in generations, the cup is back on Beaver County’s table.

Sidebar: Beaver County & Tariffs — At a Glance

How we got here

- Tokyo Round cuts (late 1970s): Average industrial tariffs fell by roughly one-third across advanced economies, embedding “free trade” as orthodoxy.

- Local shock (1984): LTV (successor to J&L) closed most of Aliquippa Works, laying off ~8,000 workers; the tin mill lingered until 2000.

- National backdrop: U.S. steel employment plunged from ~400,000 (1980) to ~164,000 (1990) amid import pressure and overcapacity.

What changed in 2025

- Baseline “reciprocal” tariff: 10% general tariff announced Apr. 2, 2025 under IEEPA.

- Steel & aluminum: Section 232 rate doubled to 50% effective June 4, 2025.

- Copper: 50% 232 tariff on semi-finished copper and copper-intensive derivatives, effective Aug. 1, 2025.

- Finished-goods expansion: 407 additional product categories (e.g., transformers, HVAC, railcars, cranes) added to the 50% steel/aluminum list Aug. 18–19, 2025.

Beaver County projects to watch

- MEPPI (New Galilee): $86M advanced switchgear factory + test lab; ~200 jobs projected; groundbreaking Mar. 19, 2025.

- 72 Steel (Aliquippa): Proposed EAF rebar mill at the former J&L site; height variances approved; timeline fluid.

- Shell Polymers (Monaca): Major local employer; “exploring strategic and partnership options” for U.S. chemicals portfolio (includes Monaca).

What the data say about tariffs’ effects

- USITC findings (232/301): Tariffs reduced imports (steel −24%; aluminum −31%), raised U.S. prices modestly (steel +2.4%; aluminum +1.6%), and increased domestic output (steel +1.9%; aluminum +3.6%).

- Household cost estimates: 2025 tariff mix ≈ $1,300 per U.S. household on average (distribution varies by income).

Logistics & industrial footprint (our edge)

- River–rail–road terminals: CRONIMET (Aliquippa) offers Ohio River barge docks, CSX rail connection, and covered/open storage—supporting heavy cargo and project freight.

- Port of Pittsburgh system: 200+ terminals across the district; historically 4th in inland tonnage; ~30M tons/year over the last decade.