Part One: A Mass of Thawing Clay

By Rodger Morrow, Editor and Publisher

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

“What is man but a mass of thawing clay?” Henry David Thoreau asked—without a thought for New Galilee brickyards or steel-furnace linings. Had he, you’d know clay was less metaphor, more take-home check.

For quite a while—by which I mean about 300 million years—Beaver County sat atop clay like an overfed cat on a sofa. One dig, and you hit it—stubborn, sticky, and begging for a kiln. Most of this geologic drama unfolded during what geologists call the Pennsylvanian Period (roughly 323 to 299 million years ago), a name that conveniently reminds the world of this state’s centrality to coal, clay, and everything built from them.

The economic usefulness of all this shifting, settling, and cosmic fermentation had to wait a few eons—until Columbus and his gang washed up with shovels, axes, and a talent for disturbing perfectly good landscapes. Only then did Beaver County’s mud begin its long, profitable career as sidewalk, furnace lining, dinnerware, and the occasional tripping hazard.

Over the years, scores of brickyards popped up across Beaver County, and well over a hundred in the wider tri-county area. That’s right: a hundred ways to bake mud within shouting distance of the Ohio.

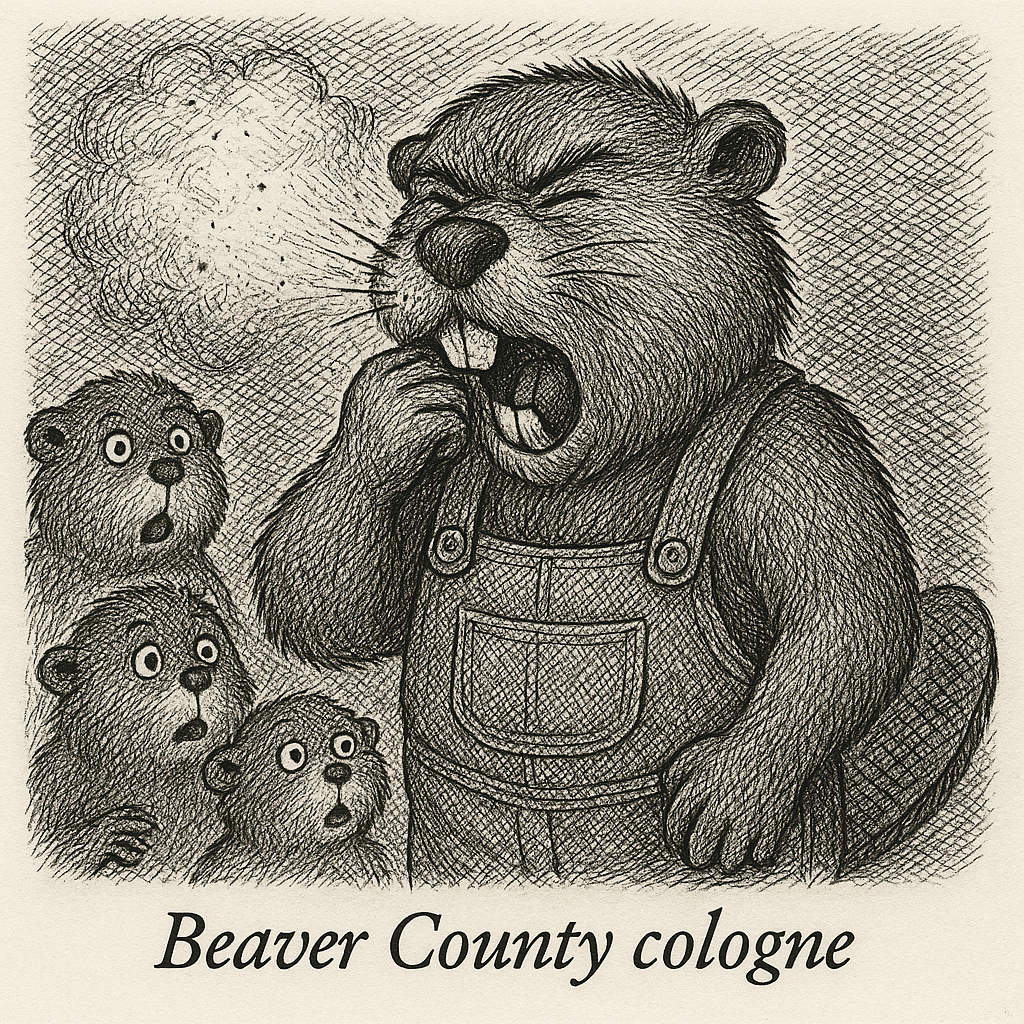

If that sounds like overkill, consider Pittsburgh’s 3,000-degree steel furnaces. Someone had to line them with firebrick—someone beaverish, as it turned out. Workers joked brick dust was “Beaver County cologne”—it followed you home, settled in your hair and boots, and sometimes even made surprise lunch appearances.

Most of those bricks had a distinct look: yellow. The iron-rich clay under Beaver County burned into the familiar buff color that gave whole rows of houses and sidewalks their golden cast. If you’ve ever wondered why so many porches in Ohio or Pennsylvania glow faintly like old teeth, odds are they rest on Beaver County’s yellow brick.

Sidewalks in Beaver Borough? Clay. Aliquippa’s blast furnaces? Clay-lining. Lightbulb insulators? Clay there, too. It was vertical integration without the Wall Street brass—just folks in overalls, shovels in hand, and kilns puffing like old locomotives.

Poetry for paving bricks? Hardly. Still, the work was dependable. Beaver Clay Manufacturing in New Galilee, founded in the 1890s, once cranked out as many as 30 million bricks in a peak year. Thirty million! I’d wager half of Ohio’s back porches rest on that run.

And, yes—rivalries. New Galilee folks swore their bricks were harder than anything New Castle could cook. New Castle boys fired back that Beaver stones made neat sidewalks but lousy furnace linings. Neither concession gained ground—though they did fuel plenty of spirited saloon debates.

Clay’s talents extended beyond bricks. McDanel Refractory Porcelain Company, founded in 1919, set up shop in Beaver Falls, producing ceramic tubes, insulators, and advanced labware. They kept the lights on—literally and figuratively—in an age racing toward electricity.

Beaver Falls also gave the world Mayer China, founded in 1881, which became a titan in hotel and institutional dinnerware. Turn over a plate at the Waldorf or the Plaza in New York and you’d find stamped on the back: Mayer China, Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania. Its reach stretched even farther: Mayer supplied the White Star Line, meaning Beaver County plates once sailed aboard the Titanic. If that isn’t geographic reach, nothing is.

Meanwhile across the river, East Liverpool styled itself “Pottery Capital of the World,” spinning teacups for folks who never paused to thank Beaver County miners for the raw clay. Down in West Virginia, Fiesta ware brightened kitchens—though the plates sometimes chipped almost as fast as they sold.

Clay didn’t discriminate. It built the millhand’s rowhouse, sat on the boss’s dinner table, and lined the most hellishly hot furnace. You could grow your whole life surrounded by it and never notice—until the whistle blew, a platter shattered, or a hidden brick tripped you right on Sunday morning.

Steel waned. Kilns cooled. Darlington’s last brickyard shut down in 2006. These days, we patch our lives with concrete blocks, vinyl siding, and tile made someplace with palm trees. Still, Thoreau had it half right. We are thawing clay—just here in Beaver County we emerged from it, one of us a paving brick, another a refractory brick, and the occasional lucky one, porcelain.

“Brick dust was Beaver County cologne.”

By the Numbers

- 100+ brickyards across Beaver and neighboring counties

- 30 million bricks in a single peak year at Beaver Clay Manufacturing

- 1919 – McDanel Refractory Porcelain founded in Beaver Falls

- 1881 – Mayer China founded; supplied hotels and the Titanic

- 2006 – Darlington’s last brickyard closed

This article is Part One of an ongoing series, A Natural (And Occasionally Unnatural) History of Beaver County. Future installments will explore coal seams, quarried stone, rivers on a rampage, atoms on the loose, and other curiosities of our landscape and lives.