Part Six: The Only Sure Thing

By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

Logstown and the First Wagers

If you want to understand Beaver County’s peculiar intimacy with gambling and “loose living,” you need to start where George Washington started: at Logstown, a cluster of longhouses and trade huts north of present-day Ambridge. In the mid-18th century, the Shawnee, Lenape, and Seneca gathered here to barter, gossip, and test their luck. Games were part of the ritual — foot races, dice-like contests, wagers on who could shoot straightest or wrestle longest.

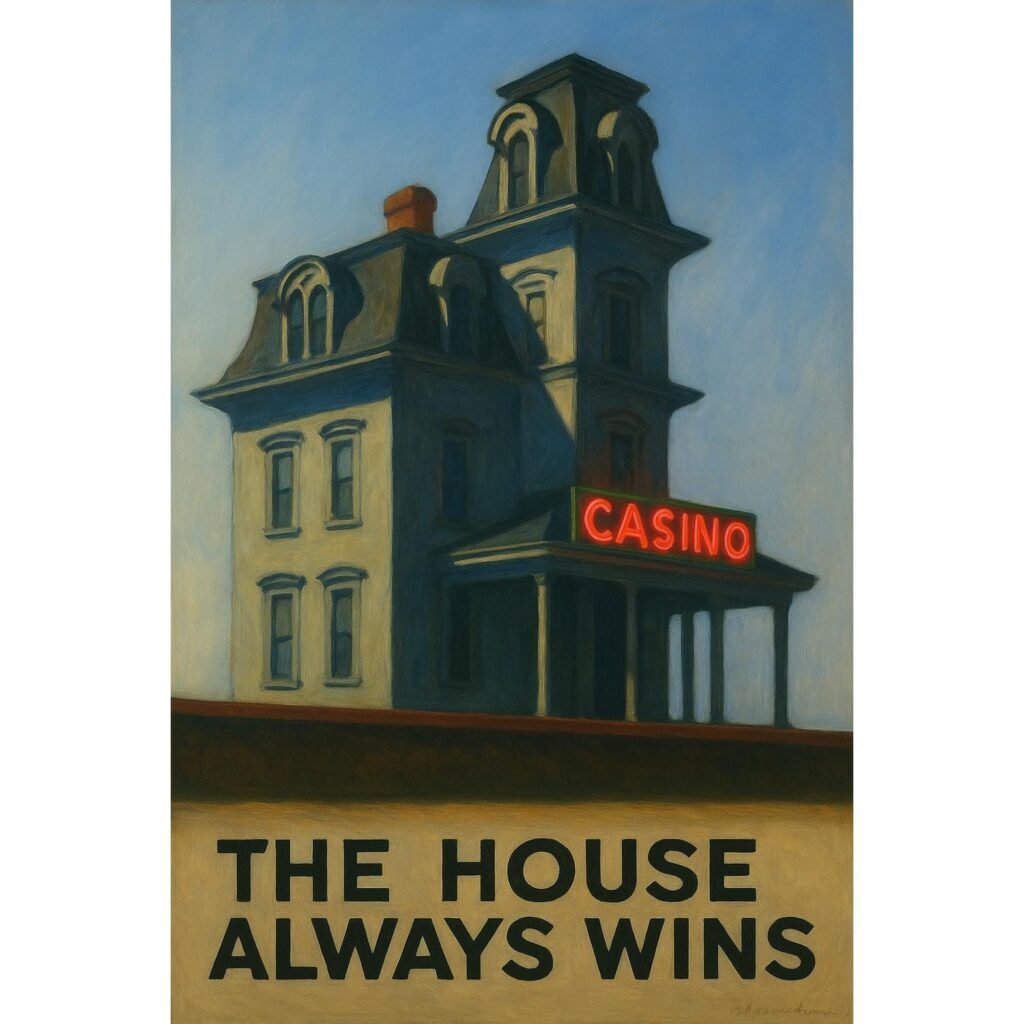

These weren’t “vices” but forms of diplomacy. The French and British envoys, forever scribbling in notebooks, were scandalized that reputation and trade might be wagered in play. Washington himself came in 1753, scribbling dutifully in his journal, and learned the first rule of the Ohio Valley: the house is always the river. If you didn’t understand the odds, you were the odds.

When Logstown faded by the 1760s, burned and abandoned in the shuffle of empires, it left behind something more durable than palisades: the habit of treating risk as a form of community entertainment.

Riverboats, Saloons, and the Long 19th Century

After Logstown vanished, the river kept playing. By the early 1800s, steamboats chugged up and down the Ohio, carrying hogsheads of pork, casks of whiskey, and sharp-eyed gamblers ready to fleece the unsuspecting. Every small-town landing — Georgetown, Beaver, Rochester, Freedom — got a taste. Farmers heading to Cincinnati learned the hard way that the “river gambler” was as much a fixture as the pilot house.

When the Beaver & Erie Canal opened in the 1830s, followed by the railroads, vice went inland. Canal towns and depots sprouted saloons like dandelions. In the back rooms, dice rattled, cards slapped, and the millworkers’ wages found new owners. Summer resorts along the river advertised “games of chance” alongside picnics and polka bands. Hypocrisy flowed more freely than lager.

By the late 19th century, Beaver County was a web of saloons, boarding houses, and beer gardens. The saloon was the workingman’s community center, and in its smoky back rooms, the local economy was laundered through cards and dice. The temperance crusaders, horrified by what went on behind the swinging doors, started demanding Prohibition. What they got in 1920 was less a moral victory than a new business model for vice.

Prohibition and the Bundle of Vice

The 18th Amendment turned the Ohio River into a smugglers’ highway. Still operators popped up in Beaver Valley basements, while liquor and cash moved through a network of bootleggers who also ran poker games, numbers slips, and brothels.

In Pittsburgh, a young cabbie named Gus Greenlee sold whiskey from the back seat and numbers slips from the front. He built an empire that funded baseball teams and jazz clubs. In Beaver County, smaller operators mimicked the formula: bundle your vices, pay off the local cop, and make sure everybody from the millworker to the mayor got a cut.

The Pittsburgh crime family, under John LaRocca and his successors, set the regional rules, but Beaver County had its own constellation of Slovak, Italian, Croatian, and Black independents. The newspapers called it “the underworld.” The locals called it Saturday night.

Raids came and went. Brothels in Aliquippa were “shut down” and reopened a week later. Slot machines were carted out of Rochester fire halls only to be wheeled back in after the headlines faded. The payoff envelope kept the wheels greased. It was an ecosystem: law, politics, and vice sustaining each other like three stubborn weeds in the same patch of ground.

Numbers, Bingo, and the State’s Cut

If bootlegging was the sin of thirst, the numbers racket was the sin of hope. For a nickel, anyone could dream of groceries, rent, or a Cadillac. Women were often the runners, selling slips from kitchens and factory lockers. The numbers were democratic in the way legislatures never managed to be.

By 1971, Harrisburg got jealous. The Pennsylvania Lottery was born, pitched as a civic duty: “Benefits Older Pennsylvanians. Every Day.” It took what the numbers had always done — turned pocket change into fantasy — and wrapped it in a seal of approval.

The churches followed with their own sanctified vice: the Bingo Law of 1981, followed by the Small Games of Chance Act of 1988. Veterans’ halls, fire companies, and parish basements became community-sanctioned gambling houses. The irony was delicious: the same politicians who railed against mob slots in the 1950s now handed out licenses for raffles in the 1980s.

Then came the collapse of steel. In Aliquippa, Beaver Falls, and Midland, mill wages evaporated. Gambling didn’t disappear; it turned desperate. Where the old vice economy thrived on abundance, the new one lived on despair.

Neon, Screens, and Smartphones

In the 1970s and ’80s, strip clubs along Route 51 and 65 became temples of bundled vice: booze, gambling, and flesh under the same neon glow. Organized crime skimmed the profits, but it was less Sinatra and more envelopes and muttered favors.

By the 1990s, a new vice economy glowed in bar corners: video poker and gray machines, technically illegal but widely tolerated. These were the bridge between pull-tabs and smartphones, keeping the ecosystem alive through the deindustrial doldrums.

Then came legitimacy, at least on paper. Rivers Casino opened in 2009. Pennsylvania launched its iLottery in 2018 and legalized sports betting, first on casino floors, then online. Today, anyone in Beaver County can place a parlay from their recliner. The same men who once whispered numbers over the bar now swipe apps between innings of a Pirates game.

Meanwhile, the “skill machines” hum in bars, veterans’ halls, and even gas stations — blinking testaments to a legal gray zone. They are the direct descendants of the numbers slips and steamboat dice, evolving but never disappearing.

Overlay all this with the opioid epidemic, and the story darkens. Addiction is no longer confined to nickels and dimes; it’s pills and poker, heroin and high-stakes keno, doubling the despair in households already strapped.

Epilogue: The House Always Wins

Three centuries on, Beaver County has played every wager: tribal contests, riverboat gambling, speakeasies, numbers, bingo, strip clubs, gray machines, iLottery, and sports apps. What changes is not the impulse but the house. Sometimes it’s the tribe. Sometimes it’s the tavern. Sometimes it’s the mob, Harrisburg, or the VFW.

What we call “vice” is less a sin than a crop — something that sprouts reliably in the Beaver Valley soil. Like knotweed along the riverbank, you can hack it down, but it grows back stronger. And the lesson remains unchanged from Logstown to the smartphone age: in Beaver County, the house always wins.