By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher, Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

Southwestern Pennsylvania has always lived with a certain dramatic flair—nothing fatal, just a habit of turning every season into a cliffhanger. The Steelers do it every December: a promising start, a little swagger, and then—right on cue—a late-season wobble that sends half the region muttering about the glory days of Chuck Noll. And if you squint, you can see a similar pattern playing out across the region itself. Pittsburgh, Beaver County, and everyone in between are trying to hold onto leads that feel a little less secure than they used to.

You see it most clearly in Pittsburgh, the old heavyweight who’s still got the jawline but not quite the footwork. The steel era collapsed, the glass towers thinned out, and the city remade itself as the Silicon Valley of the Alleghenies. For a while it stuck. Tech firms arrived, CMU generated dissertations by the bushel, and Google decided to treat the Monongahela like its second home.

But beneath the tech glitter, Pittsburgh leaned—very heavily—on one sector: health care. UPMC and AHN together employ well over 120,000 people. Add it all up, and health care became the region’s gravitational center. And with Allegheny County losing more than 25,000 residents since 2020—more deaths than births, more departures than arrivals—the industry hummed along by serving an older, sicker region. For a while it looked recession-proof.

Now the cracks are showing. Healthcare affordability in southwestern Pennsylvania is among the worst in the state: 58% of adults report cost burdens, and more than half have delayed or skipped care entirely because they couldn’t afford it. Even a giant like UPMC can’t outrun that kind of math forever. When a region builds its future on treating an aging population that’s simultaneously shrinking and priced out of care, you don’t just get an economic problem—you get a demographic one.

But this isn’t just Pittsburgh’s story. It’s the whole region’s story. And that means Beaver County is tied to Pittsburgh’s fortunes far more tightly than either place likes to admit.

Beaver County, for its part, has been mounting a comeback of its own. Shell’s plastics plant—now known to have cost roughly $14 billion, not the originally estimated $6 billion—landed on the Ohio like an aircraft carrier. It hasn’t performed financially as Shell once hoped, but the sheer scale of the investment still matters. Mitsubishi Electric Power Products is expanding with $86 million and at least 200 new jobs. And Frontier Group’s $3.2 billion project in Shippingport—a natural gas power station conversion that includes a data center—signals a massive pivot on a site once defined by coal.

Add to that the B-HIVE ecosystem—Penn State Beaver, CCBC, and the Beaver Valley LaunchBox—an innovation lab that’s become one of the region’s more promising talent engines. Something’s stirring in Beaver County; you can feel it.

Still, some of the numbers being talked about—potentially $500 million in new investment, 15,000 jobs, and a 20–30% population increase by 2035—should be understood as aspirational projections, not confirmed commitments. They’re a vision, not a ledger entry.

But regions are built on vision, and Beaver County’s at least feels directional.

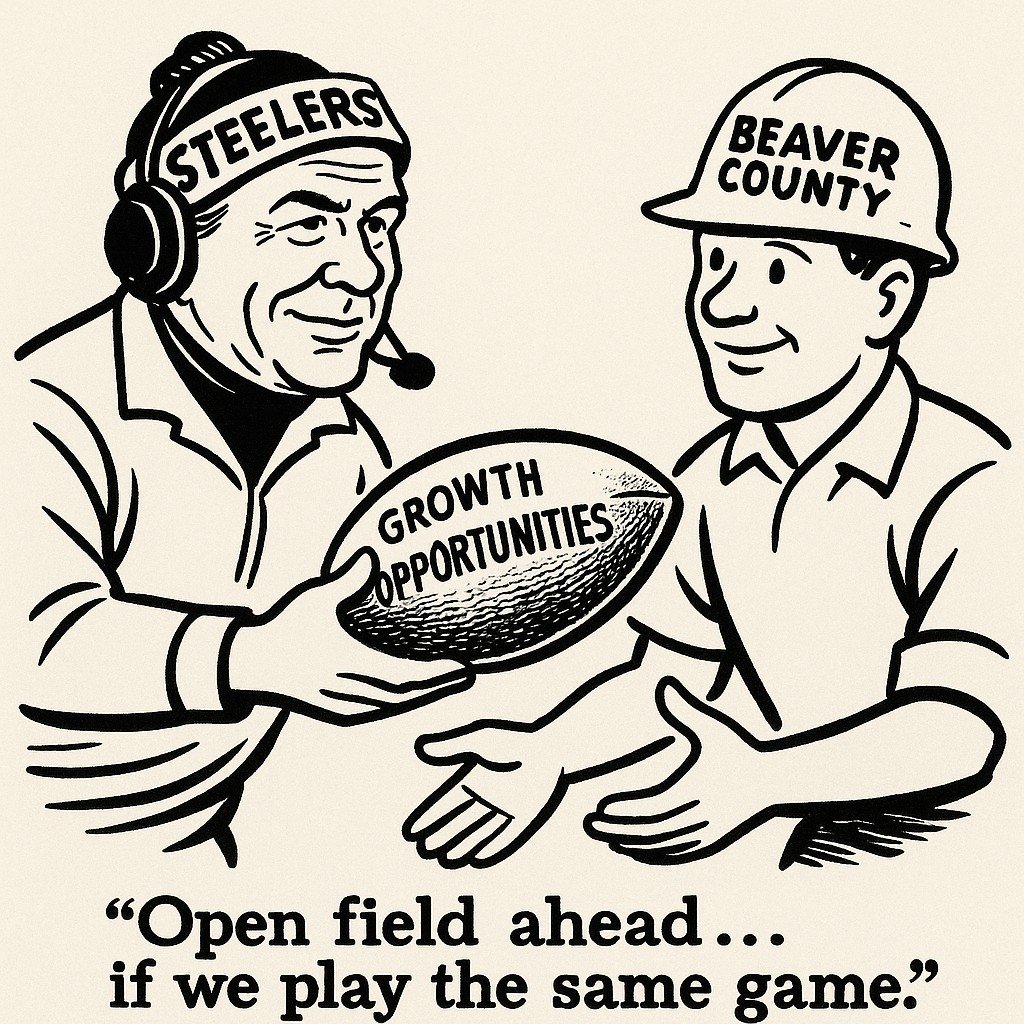

Here’s the important point: Pittsburgh’s struggles and Beaver County’s opportunities are not parallel stories. They’re braided together. If Pittsburgh’s downtown continues to empty out, the whole region feels the draft. If Beaver County succeeds in capturing a significant share of new energy, manufacturing, and data infrastructure growth, the entire region gains a stabilizing spine. If Pittsburgh’s health-care-heavy economy wobbles, Beaver County’s more diversified base becomes a counterweight. And if Beaver County can’t grow its workforce, Pittsburgh’s universities can’t keep exporting talent downstream.

It’s not a rivalry. It’s a three-legged race where one partner is winded and the other is picking up speed.

And frankly, neither can go it alone. Pittsburgh needs the land, the industrial capacity, and the breathing room Beaver County offers. Beaver County needs Pittsburgh’s universities, global recognition, and gravitational pull. The future of Southwestern Pennsylvania won’t be shaped by municipalities acting like medieval fiefdoms, but by whether the old champion and the emerging contender can learn to move in the same direction.

The risk isn’t that Pittsburgh becomes a ghost city. The risk is that the region refuses to act like a region.

The solution’s simple enough to paint on a billboard along I-376: Pittsburgh and Beaver County: Not Rivals. Co-Stars.

And if we get that right, Southwestern Pennsylvania’s fourth quarter might be its best yet.