By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher, Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

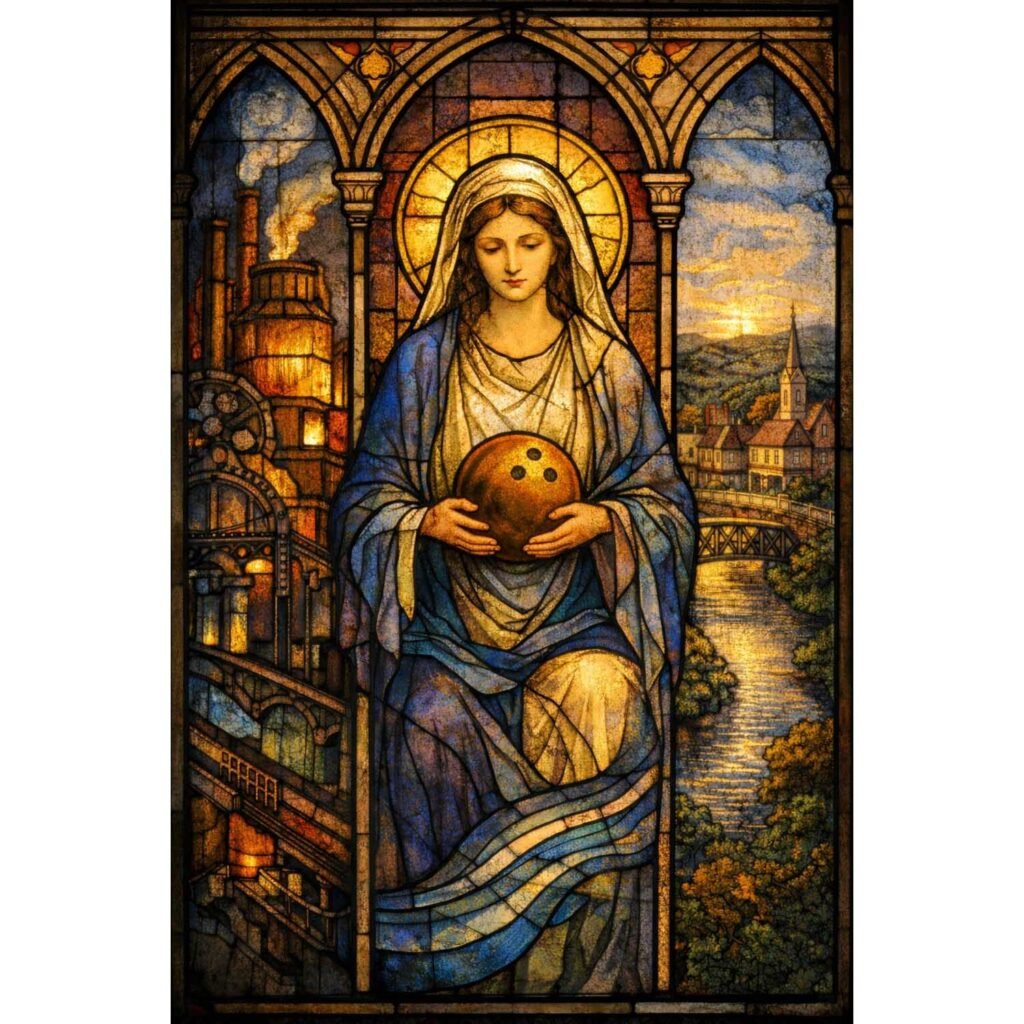

Beaver County has been living between the Dynamo and the Virgin for so long that most of us scarcely notice the tension anymore. It’s simply the background hum of daily life—the Ohio River sliding past in one direction while history insists on flowing in the other.

The phrase comes from Henry Adams’s The Education of Henry Adams, whose author stood in Paris in 1900 staring at a massive electrical generator and felt something like religious vertigo. The dynamo, Adams realized, was the new god: silent, invisible, infinitely powerful, and entirely indifferent to human meaning. Against it he set the Virgin Mary, whose medieval energy—creative, compassionate, unifying—had once summoned cathedrals, art, poetry, and a shared sense of order out of chaos. Adams felt stranded between the two kingdoms of force, too modern for faith and too human for machinery.

If he had wandered a little farther west and a little earlier in time, he might have felt right at home in Beaver County.

From its beginnings, this place has been shaped by raw power. Irish canal workers—navvies armed with picks, shovels, and a remarkable tolerance for misery—cut channels through mud and stone so goods and people could move faster than nature intended. Railroads followed, and then furnaces, foundries, and mills whose roar became the county’s unofficial anthem. The dynamo announced itself early and loudly here, first as waterpower and steam, later as electricity, steel, and industrial mass.

Yet running alongside that noise was something quieter and far more stubborn.

The same county that mastered blast furnaces also produced Henry Mancini, whose melodies drifted into living rooms around the world with a sophistication that made West Aliquippa sound improbably cosmopolitan. You don’t write “Moon River” by accident. You write it because somewhere inside the clatter of machines, someone taught you to listen for tenderness.

This is the paradox Beaver County keeps turning over like a worry stone. For every engineer, there is an artist; for every machine shop, a music room.

Consider the engineers themselves. Albert Lucius and John Augustus Roebling embodied the heroic age of American engineering—men who believed discipline, mathematics, and courage could quite literally suspend order over chaos. Roebling’s bridges weren’t merely functional; they were acts of faith in tensile strength and human ingenuity—cathedrals made of wire.

Or consider the far-flung influence of the Michael Baker Corporation, whose projects carried Beaver County’s practical intelligence to highways, pipelines, and cities well beyond the Ohio Valley—even as far as Saudi Arabia. This was the dynamo at its most impressive: organized power serving human ambition at continental scale.

And yet, if Adams were standing here today, he might be surprised by how persistently the Virgin refuses to leave town.

Walk into the Merrick Art Gallery in New Brighton and you step into a 19th-century dream of beauty preserved, even defended, inside a former railroad station. Hudson River landscapes hang salon-style, insisting that nature, light, and contemplation still matter. A piano once played by Stephen Foster sits quietly in its room, a reminder that melody can outlast machinery. It doesn’t scale. It doesn’t hum. And yet it endures.

Or visit Midland, where the collapse of the steel industry might have been expected to leave only rust and resignation. Instead, the old Lincoln High School site became Lincoln Park Performing Arts Charter School, a place where teenagers rehearse Shakespeare, practice arias, and learn stagecraft in buildings once shadowed by blast furnaces. If that isn’t the Virgin slipping back in through a side door, it’s hard to say what is.

Henry Adams feared modern humanity had traded unity for speed, meaning for multiplicity. Beaver County, without ever consulting the theorists, has been running that experiment for two centuries.

The dynamo is still here, of course. Today it hums more quietly—in data centers, logistics systems, global supply chains, and algorithms that make decisions faster than any steel roller ever turned. Its indifference has only grown more refined. It no longer roars. It whispers.

And still, the Virgin persists.

She appears in church basements where canal workers once knelt after twelve hours in the mud. She lingers in music classrooms, art studios, ballet classes, and community theaters. She shows up whenever someone decides that efficiency alone is not enough—that life also requires beauty, memory, and a story worth telling.

Beaver County has never resolved the tension Henry Adams described. It has simply learned to live inside it. The result is a place where engineers write symphonies, artists grow up in mill towns, and power is forever shadowed by grace.

If the dynamo promises infinity, the Virgin insists on meaning. And here, between river and rail, furnace and gallery, we are still—sometimes clumsily, sometimes beautifully—trying to hold on to both.