By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher, Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

If America ever produced a patron saint of thinking ahead…

If America ever produced a patron saint of thinking ahead, it was Benjamin Franklin—the man who could squeeze a penny so hard it developed character, start a university between experiments with lightning, and design a 200-year investment plan while most of us are still deciding whether to hit the snooze button. In a nation now living on impulse, Franklin was the rare Founding Father who lived on compound interest.

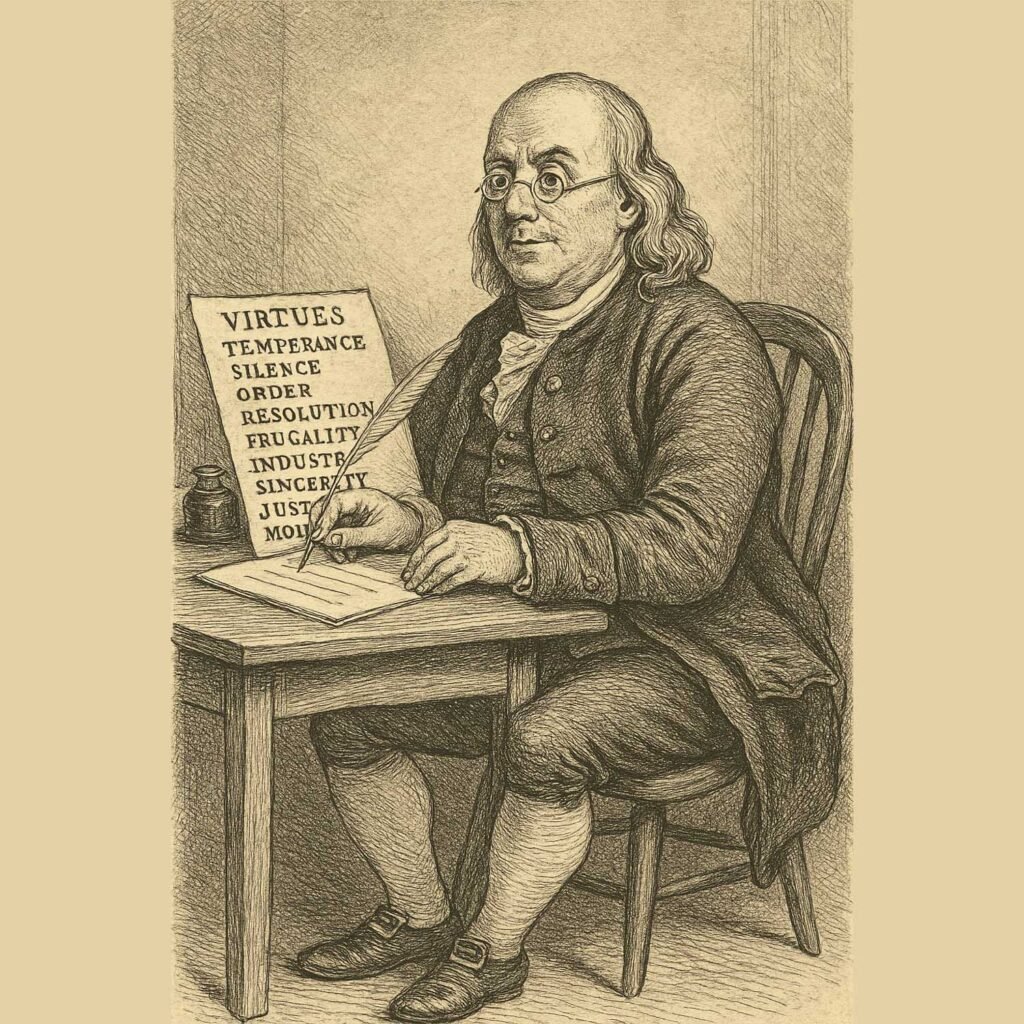

He began life not as the sage of the $100 bill, but as a printer’s apprentice of such modest means that his entire net worth would have fit neatly in the till of a Bridgewater lemonade stand. He was poorly educated, frequently hungry, and surrounded by older brothers who took turns reminding him he would never amount to much. Franklin’s response was not self-pity but self-education. He woke at five, tracked every hour of his day, and trained himself in languages, science, philosophy, and statesmanship. He built what amounted to the first American self-improvement app—his famous 13 virtues chart—except instead of push notifications, it had guilt.

Franklin understood the secret that every actuary and Amish farmer knows: everything compounds—money, knowledge, reputation, even character. But compounding requires time, and time requires patience, and patience is the one virtue modern America treats like a communicable disease. By his early forties, Franklin had quietly become one of the wealthiest men in Pennsylvania, not because he earned extravagantly, but because he consumed sparingly. He lived for long stretches on bread and water so he could spend his money on books, tools, and the printing equipment that made him financially independent by 42.

A Second Life Built on Patience

And then, having achieved the impossible—retiring young without inheriting a copper mine—he embarked on a second career that made the first look like warm-up laps. While most early retirees take up golf, Franklin took up nation-building. He founded the first lending library, the first volunteer fire department, a militia, a hospital, a college, a postal system, and even Philadelphia’s street lighting and paving standards, all without the faintest expectation of getting rich from any of it. He simply believed a city—and later a country—should function better long after he was dead, a sentiment so unfashionable today it might qualify as a mental disorder.

The Longest Investment Horizon in American History

Franklin’s greatest demonstration of low-time-preference thinking came at the end of his life. In 1789, he left £1,000 each to Boston and Philadelphia with instructions that the money be lent to young apprentices and not fully touched for 100 years. The remainder, he specified with serene confidence, should then continue compounding for another century.

In other words: “I’ll be dead, you’ll be dead, your grandchildren will be dead—let’s see what happens.”

What happened was a real-world miracle of compounding. By 1990, Franklin’s relatively modest gift—about $120,000 in today’s money—had grown to roughly $6.5 million. And in a twist that would have delighted him, the Beaver County Foundation, established in 1992, was seeded with a $25,000 gift from Franklin’s estate, making Beaver County itself a minor beneficiary of his extraordinary patience. Our own philanthropic engine, in other words, is running partly on an 18th-century time-delay fuse.

The Operating System of a Lifetime

All of this was possible because Franklin engineered a personal operating system designed to strangle impulsiveness. His 13 virtues weren’t moral niceties; they were a daily assault on instant gratification. Temperance to avoid gluttony. Silence to avoid gossip. Order to avoid chaos. Frugality to avoid nonsense purchases. Industry to avoid laziness. Tranquility to avoid blowing a gasket over trifles. It was behavioral finance before the term existed, a system for compounding character the same way he compounded wealth.

He confessed in his Autobiography that he never reached perfection, but that the pursuit made him “a better and a happier man” than he otherwise would have been. Translation: he didn’t expect results tomorrow. He expected them in decades. He placed his bets on the slow curve—the only curve that never lies.

Franklin and Beaver County: A Shared Philosophy

In our current high-time-preference America—where we refinance cars to buy bigger cars, where sleep schedules resemble the habits of raccoons, and where “long-term” means waiting until the next iPhone release—Franklin stands out like a man calmly reading Poor Richard by candlelight while the rest of us shout into smartphones about back-ordered air fryers.

Yet Franklin feels oddly at home in Beaver County. Ours is a county built by long-game people: steelworkers who saved, farmers who planted for future harvests, grandparents who canned peaches for winters they might not live to see. The Beaver County Foundation itself is a monument to patience—one seeded, improbably, by a Founding Father who thought in centuries.

The Question Franklin Leaves Us

Franklin sacrificed comfort for craft, pleasure for posterity, impulse for infrastructure. He bent his entire life toward a future he would never see—and the country is still collecting the interest. Which raises the question: if one frugal printer could think in centuries, why can’t the rest of us think past this Friday?