By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher, Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

Arthur Schopenhauer never attended a zoning hearing, a school board meeting, or a Chamber breakfast. This is unfortunate, because it would have confirmed many of his darkest suspicions about human nature and saved the rest of us several centuries of trial and error.

Schopenhauer, a 19th-century German philosopher with the bedside manner of a porcupine, believed that genuine thinking was a minority pursuit. Most people, he observed, do not reason their way to conclusions. They arrive by instinct, emotion, habit, or tribal loyalty, and then build a small picket fence of logic around whatever they’ve already decided to believe. Thinking, in the rigorous sense, was rare enough to qualify as an anomaly.

He was not being cruel. He was being architectural.

Some minds, Schopenhauer argued, simply are not built for complex loads. Abstract reasoning, contradiction, and delayed gratification exceed the structural limits. This is not a matter of laziness or bad character. It is a matter of design. You cannot retrofit a ranch house to support a cathedral dome, and you cannot argue someone into understanding an idea their cognitive framing cannot hold.

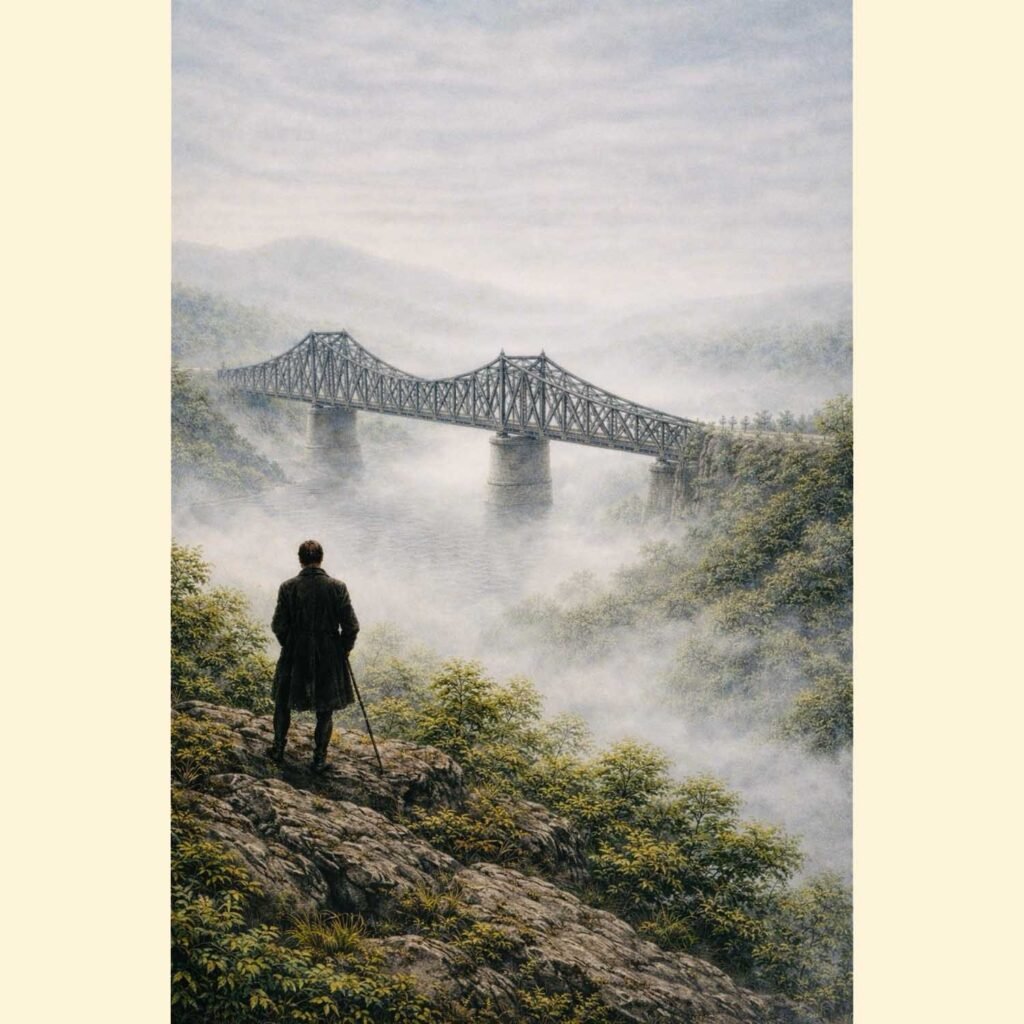

One of Schopenhauer’s most quoted observations remains painfully relevant: “Every man takes the limits of his own field of vision for the limits of the world.” In other words, if you cannot see beyond your own assumptions, the problem is not that the world is complicated. The problem is that you are standing too close to the wall.

This helps explain a phenomenon we now label with academic precision—the Dunning-Kruger Effect—but which Schopenhauer spotted long before psychology had a lab coat. Those with the least capacity for understanding often possess the greatest confidence. Doubt requires imagination. To question oneself, one must be able to conceive of being wrong. When that capacity is missing, certainty arrives early and speaks loudly.

This creates a peculiar social dilemma for people who do think carefully. To someone without intellectual range, intelligence is invisible. Or worse, it looks like overcomplication, evasion, or pretension. Nuance sounds like weakness. Caution looks like ignorance. A carefully qualified answer is dismissed in favor of the person who pounds the table and announces, with confidence, that the matter is settled.

Schopenhauer’s advice to the intelligent was not to reform society or withdraw to a mountaintop. It was simpler and more humane: adjust your expectations.

Stop expecting original thought. Expect repetition. Expect slogans, memes, and beliefs installed fully formed, like software no one remembers downloading. Expect emotional reasoning—where a conclusion is reached first, and logic is reverse-engineered afterward to justify it.

And above all, don’t argue against feelings. You cannot reason someone out of a position they did not reason themselves into. Logic is not persuasive to those who use it the way a drunk uses a lamppost: for support, not illumination. Prolonged debate in such cases does not elevate understanding; it drags clarity down to the lowest common denominator until all nuance is lost and everyone goes home equally dissatisfied.

There is also a protective dimension to this philosophy. Guard your clarity. Engaging endlessly with limited thinkers forces you to simplify, then oversimplify, until the truth resembles a bumper sticker. Over time, you begin to doubt not your conclusions, but your capacity to express them without distortion.

Schopenhauer even recommended a kind of strategic discretion. Not concealment born of shame, but selectivity born of wisdom. Share your depth with those who can meet you there. They exist, though they are fewer than we might like. Conversation, after all, is not a mass activity. It is a pairing of compatible instruments.

What this philosophy is not is cruelty or contempt. It is not an argument for isolation or cynicism. It is an argument for efficiency. By accepting the world as it is—uneven terrain, soft ground here, solid footing there—you conserve energy and preserve peace.

For people engaged in business, civic life, or leadership, this realism is not pessimism. It is a survival skill. When you understand that most people respond to authority, emotion, and familiarity rather than evidence, you can navigate institutions with something like surgical precision.

And in Beaver County, this can be especially useful.

Anyone who has ever sat through a public meeting where a five-minute agenda item somehow consumes an hour, or watched a serious economic discussion get derailed by a Facebook rumor, knows exactly what Schopenhauer meant. The trick is not to win every argument. The trick is to know which arguments are worth having—and which ones are better observed quietly, like weather.

Because here, as everywhere, intelligence is rare, certainty is plentiful, and progress usually arrives not with applause, but with the quiet relief that at least this time, the bridge got built and the meeting ended on time.