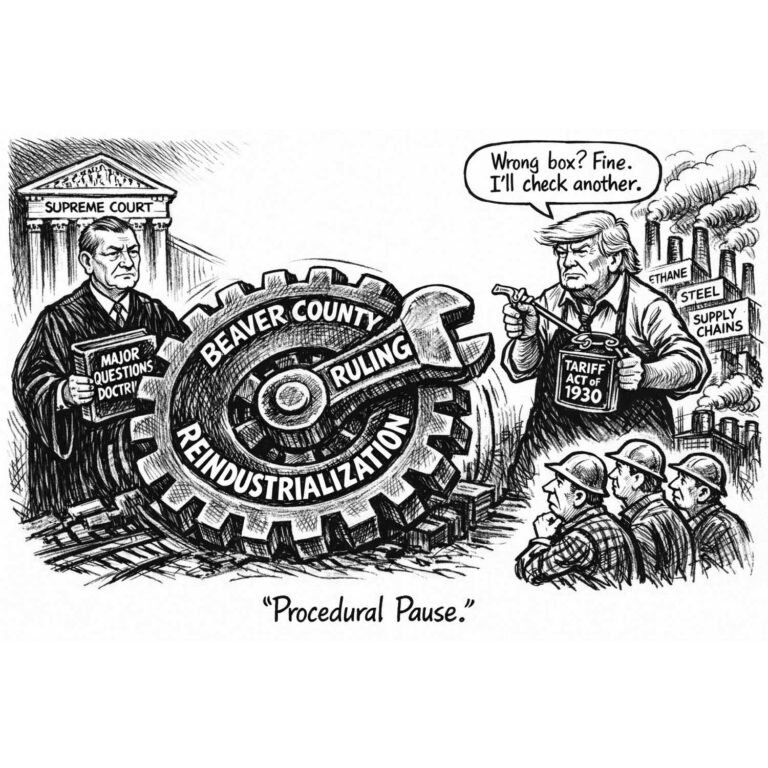

By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

Hugh Henry Brackenridge: Frontier Satirist

Hugh Henry Brackenridge (1748–1816) was the sort of fellow who could have lived a perfectly respectable life on the Philadelphia side of the Alleghenies—Princeton graduate in 1771, Revolutionary War preacher in 1776, lawyer in training soon after—all the right credentials. But in 1781, he had the poor judgment (or the inspired madness) to load a printing press on a wagon and haul it across the mountains into the raw settlements of Western Pennsylvania. Imagine pushing a grand piano up Route 28 today, and you get the idea.

On the far side, he made himself indispensable as a lawyer, orator, newspaper editor, and professional gadfly. He opened Pittsburgh’s first newspaper, the Pittsburgh Gazette, in July of 1786, and set about making himself the tribune (and irritant) of frontier democracy. Brackenridge saw that civilization was marching westward whether it was ready or not, and he intended to be there first—with a sermon, a statute, or a sharp satire. His great comic novel, Modern Chivalry, began appearing in installments in 1792, with additional volumes published through 1815.

Captain Farrago and Teague O’Regan

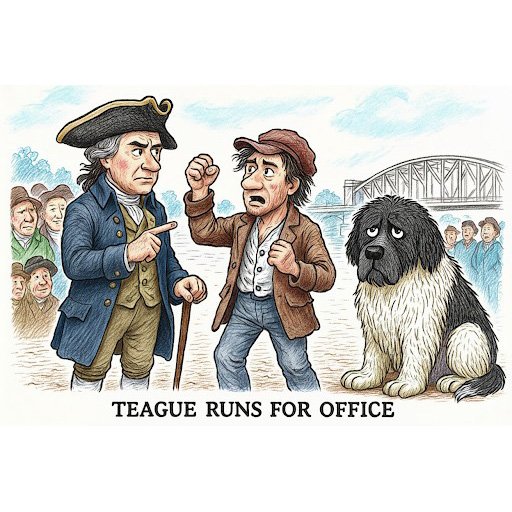

In place of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, he gave us Captain John Farrago—a gentleman farmer with lofty notions—and Teague O’Regan, his thick-headed Irish servant who could be talked into any ambition from legislator to diplomat. Together they stumble through the Western frontier, encountering tavern debates, impromptu elections, militia musters, and every form of democratic mischief a young republic could dream up.

And the ground they stumble over is familiar. When Brackenridge wrote of taverns at river crossings, of muddy streets and makeshift courthouses, he was sketching the same Ohio Valley corridor that ran past Fort McIntosh (established 1778 at present-day Beaver), past the nearby settlement at Logstown (a short walk from today’s Aliquippa), and the training grounds of General “Mad” Anthony Wayne’s Legionville encampment (1792–93, near present-day Baden). These were the outposts that gave way to towns like Beaver, Bridgewater, Rochester, and Freedom.

Sidebar: Beaver County on Brackenridge’s Frontier

Fort McIntosh (1778)

Built by the Continental Army on the bluff above today’s Beaver, this was the westernmost American fort during the Revolution. Officers and militiamen stationed here kept order in the Ohio Valley just as Brackenridge’s Captain Farrago was wandering the countryside in Modern Chivalry.

Logstown (Aliquippa area)

Once a major Native American village and trading hub, Logstown by the 1780s had become a way station for settlers and speculators. Brackenridge’s characters—stopping at every tavern, ferry, and crossroad—would have passed through communities much like this one.

Legionville (1792–93)

General Anthony Wayne’s winter training camp, near present-day Baden, was the first formal basic training site in U.S. Army history. The same year Brackenridge published the opening volume of Modern Chivalry, Wayne was drilling recruits here for the campaign that secured the Northwest Territory.

From Outpost to County Seat

The cabins and clearings Brackenridge sketched in satire grew into Beaver, Bridgewater, Rochester, Freedom, and the rest of Beaver County. Reading his comic novel today, it’s not hard to imagine Farrago and Teague blundering down Third Street, still arguing about whether a weaver—or a stable boy—belonged in the legislature.

A Chapter in Brief

At a frontier election, a weaver offers himself as a candidate for the legislature, only to be mocked by a more educated rival. Captain Farrago intervenes to argue that weaving cloth is no qualification for weaving laws and persuades the weaver to stand down. Unfortunately, Teague seizes on the moment and declares his own candidacy. The crowd, intoxicated by its democratic prerogative, nearly elects him, until the Captain convinces his servant that public life would only earn ridicule. Teague withdraws, the weaver takes the votes, and the republic survives another day.

Modern Chivalry, Book I, Chapter 3 (abridged)

The Captain, rising early the next morning and setting out on his way, arrived at a place where a number of people were convened for the purpose of electing persons to represent them in the legislature of the state.

There was a weaver who was a candidate for this appointment and seemed to have a good deal of interest among the people. But another, a man of education, was his competitor. Relying on some talent of speaking which he thought he possessed, he addressed the multitude:

“Fellow citizens, I pretend not to any great abilities; but I have the best goodwill to serve you. Yet it is astonishing that this weaver should conceive himself qualified for the trust. Though my acquirements are not great, his are still less. The business he pursues must necessarily take up so much of his time that he cannot apply himself to political studies. It would be more answerable to your dignity, and conducive to your interest, to be represented by a man of letters than by an illiterate handicraftsman like this.”

The Captain, hearing these observations and looking at the weaver, could not help advancing:

“I have no prejudice against a weaver, nor do I know any harm in the trade—save that from the sedentary life in a damp place, there is usually a paleness of countenance. But to rise from the cellar to the senate house is an unnatural hoist. To come from counting threads to regulating the finances of a government is preposterous. There is no analogy between knotting threads and framing laws.”

While the Captain discoursed, Teague, hearing so much about elections and government, took it into his head that he could be a legislator himself. The crowd, amused by novelty, encouraged the idea. The Captain protested that Teague was illiterate, ignorant of geography, commerce, and finance, and scarcely able to speak the language in which laws must be written. But the people insisted on their right to elect whom they pleased.

At last, the Captain pulled Teague aside and warned him that he would be ridiculed in newspapers and caricatured by wits. Moved by the prospect of becoming a laughingstock, Teague agreed to withdraw, leaving the people to give their votes to the weaver.

Brackenridge’s Place in American Letters

Brackenridge lived out his days in Pittsburgh, serving as a state legislator, state supreme court justice, and unrepentant mischief-maker until his death in 1816. By then, Modern Chivalry had sprawled into six volumes, the last appearing just a year before he died. Henry Adams, no easy dispenser of praise, later ranked him among America’s first truly original literary voices. Long before the nation had a Hawthorne or a Twain, Brackenridge had already skewered democracy’s follies in the taverns, cabins, and courthouse squares of Western Pennsylvania—with a printing press, a biting wit, and an Irish servant who wouldn’t stop running for office.