By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher, Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

If you’re reading this, allow me to offer a small civic salute. You’ve just accomplished something quietly heroic: you sat still, focused your attention, and followed a line of thought all the way from the left margin to the right.

In 2026, this places you somewhere between a Benedictine monk and an Olympic endurance athlete.

Reading, it turns out, is not something humans were ever meant to do. We were designed to spot predators, gossip around campfires, and remember where the berries were last season. The alphabet showed up late to the party. When it did, the brain improvised—grabbing spare parts from the visual system, the speech center, and the memory warehouse, wiring them together into a contraption that somehow lets black squiggles on a page turn into ideas, images, and occasionally better judgment.

All of this happens in less than half a second. You don’t feel it because the brain, like a good stagehand, prefers to work behind the curtain. But while you’re reading this sentence, a tiny patch of cortex originally intended for recognizing faces has been reassigned to recognize words, which are then passed along—like a baton in a relay race—to regions that handle sound, meaning, memory, and context. The whole operation is an elaborate neurological Rube Goldberg machine, and the fact that it works at all is frankly astonishing.

What matters is what happens next.

When you read regularly, the brain doesn’t just absorb information. It builds connections—thickening neural pathways, multiplying associations, and creating alternate routes for memory and recall. Think of it as adding side streets and back roads to the mind. Later in life, when a few bridges inevitably go out, readers have options. This “cognitive reserve” helps explain why habitual readers tend to remember more, regulate emotions better, and fend off mental decline longer than their non-reading counterparts.

Reading also performs a second, more subversive function: it trains us to be other people. When a book describes cold air, your sensory cortex reacts as if the temperature dropped. When a character grips a doorknob, your motor cortex practices along. And when a story invites you inside someone else’s head—someone flawed, foreign, irritating, or morally ambiguous—your brain rehearses empathy. You learn, neuron by neuron, how to imagine a life that is not your own.

This is not a literary parlor trick. It is the operating system of a functioning society.

For most of the last century, newspapers provided a shared mental commons. You might argue about the conclusions, but at least you were reading the same facts, the same headlines, the same account of what happened yesterday. Literacy made disagreement possible without making conversation impossible. It was the quiet glue of citizenship.

Today, that glue is dissolving. Modern media trains the brain to expect novelty every few seconds. Alerts buzz. Clips flicker. Attention ricochets. Every interruption collapses the fragile inner world that reading creates, and when we return, we do so from a shallower place. Skimming replaces thinking. Reaction replaces reflection.

Deep reading is the antidote. It forces us to slow down to a human pace and stay there long enough for meaning to sink in.

Which brings us, inevitably, home.

By the official numbers, Beaver County’s literacy is “average.” We graduate high school at impressive rates. Student reading proficiency tracks the state mean. On paper, everything looks respectable—mid-pack, solid, no cause for alarm. But “average” is not the same thing as healthy, and it is certainly not the same thing as prepared.

Counties that are pulling ahead—places like Chester or Allegheny—also happen to read more, learn longer, and earn more. Literacy, numeracy, and opportunity tend to travel together. Where one lags, the others usually follow.

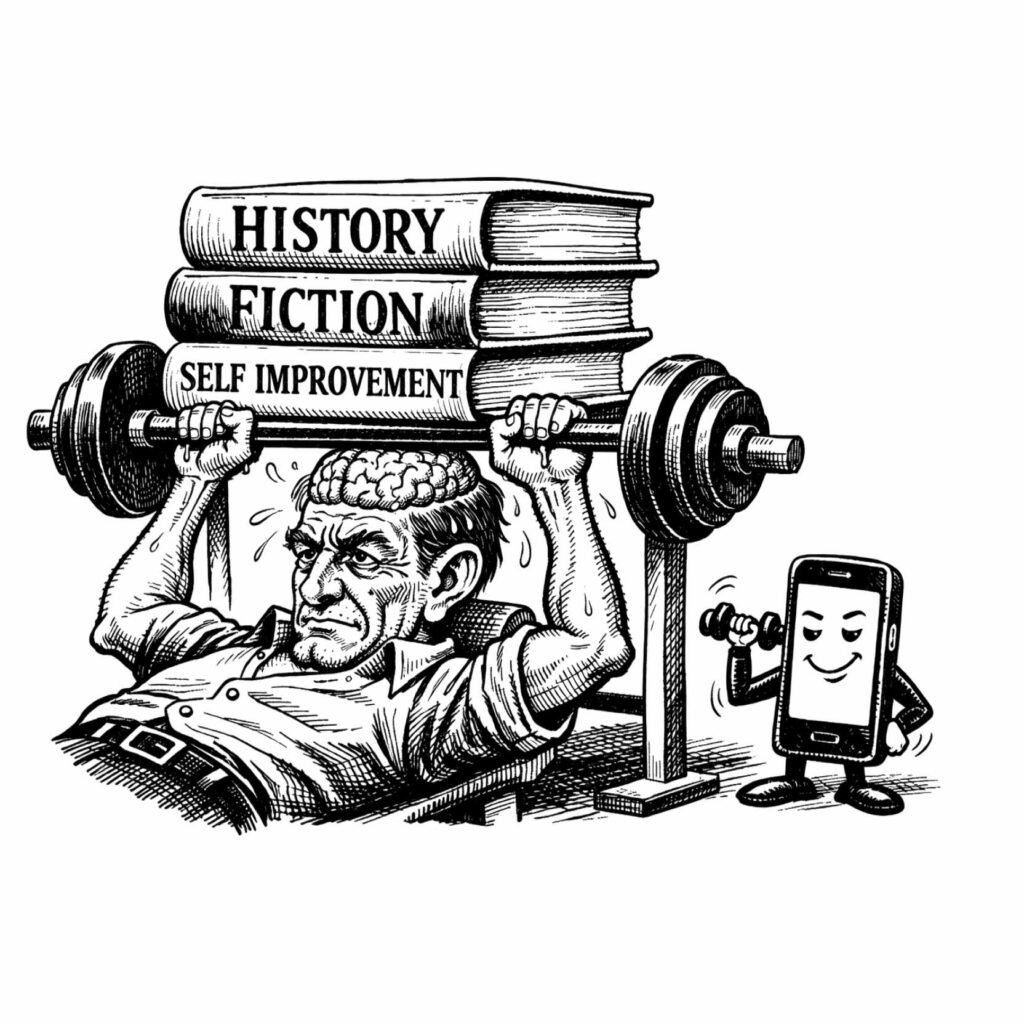

And literacy is not a trophy you win at eighteen and put on the shelf. It is a muscle. Use it, and it strengthens. Ignore it, and it weakens—quietly, politely, without making a fuss.

This should concern us, because Beaver County is doing many of the right things. We’re wiring the county with broadband. We’re talking seriously about advanced manufacturing, AI, and data centers. All necessary. None sufficient.

You can blanket the hills with fiber and fill warehouses with servers, but if a population cannot read deeply, think patiently, and imagine perspectives beyond its own, the technology becomes an expensive noise machine. Signal degrades. Judgment falters. Clever tools end up doing foolish things very efficiently.

The good news—there is always good news—is that it’s never too late. Adults who return to reading still reap the neurological rewards. Ten pages. Ten minutes. A book before bed instead of a phone. Distractions in another room. Habits rebuilt one paragraph at a time.

This isn’t nostalgia talking. It’s biology.

If Beaver County wants to flourish—not just economically, but civically and humanly—we need to treat reading the way we once treated electricity and clean water: as essential infrastructure. Libraries matter. Schools matter. Parents matter. Employers matter. Local newspapers matter.

Because if you’re reading this, your brain is already doing the work.

The question is whether we’re willing to help the rest of the county do the same—before all our gleaming new machines arrive to discover there’s no one quite ready to use them wisely.