By Rodger Morrow,

Editor & Publisher, Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

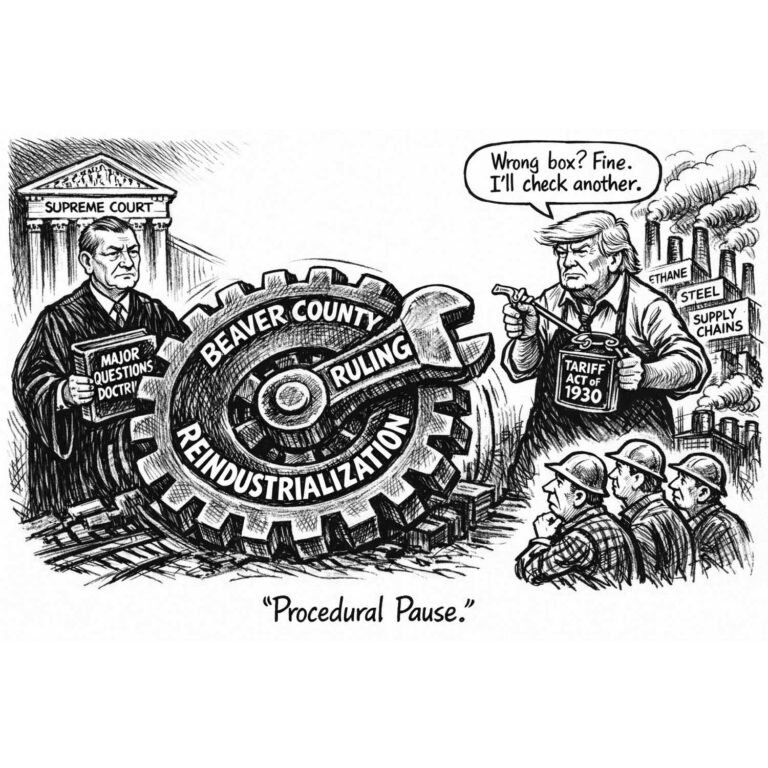

It may well be, as the late Charlie Kirk argued, that university education is a bad economic bargain for many young people these days.You can spend four years and six figures learning how to deconstruct gender hierarchies in 14th-century French poetry, only to graduate into an economy that would prefer you learn how to repair a diesel engine. Point taken. But in the rush to write off higher education as a racket, let’s not throw the Gutenberg out with the bathwater.

Books, unlike TikTok videos or Instagram reels, still allow the mind to move at its own pace

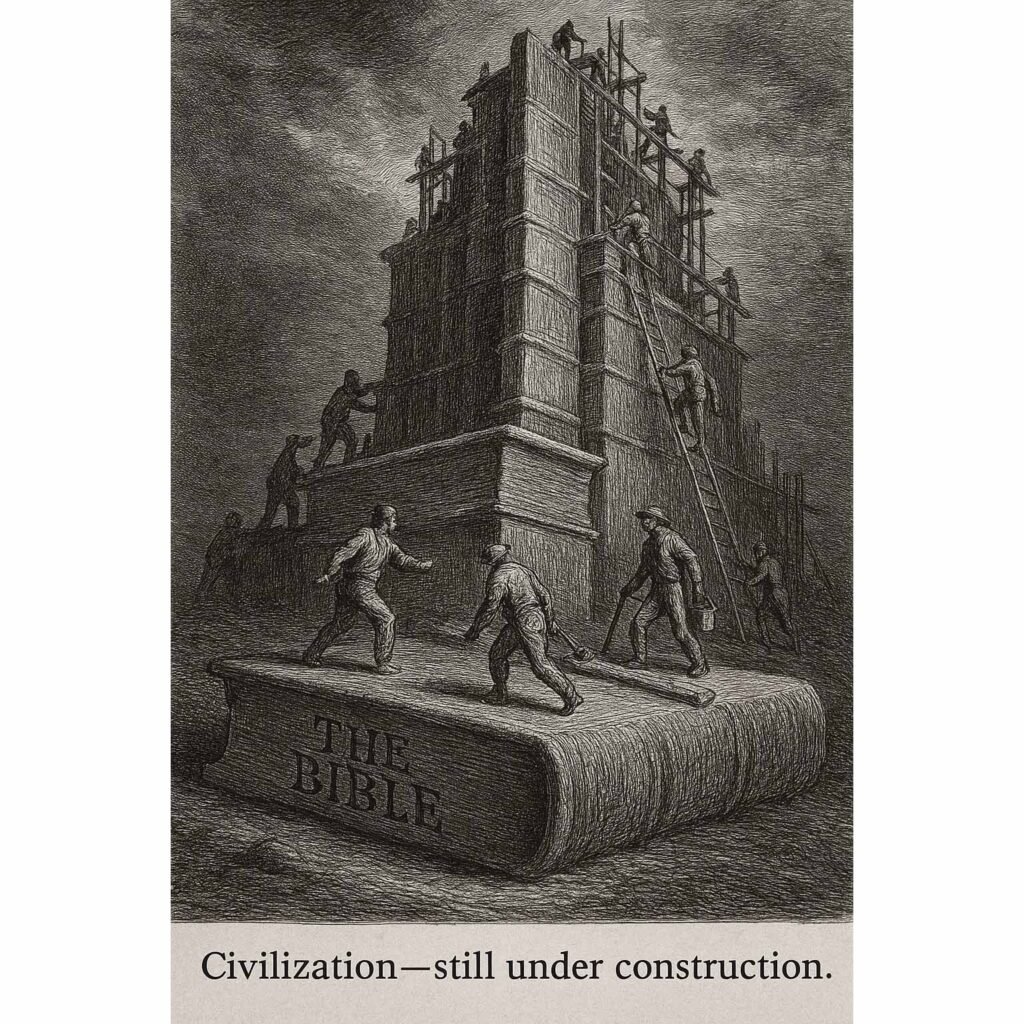

—whether briskly or ploddingly, whether to engage, argue, underline, or just sit with a single sentence for a week. Books aren’t designed to disappear in 12 seconds or be forgotten in 12 minutes. They are meant to endure, and in enduring, they give us the tools to endure as well.

We’ve spent thousands of years stacking stone upon stone

invention upon invention, word upon word, to build what passes for the world’s most successful civilization. Books have been the scaffolding of that success—especially the Book of all books, the Bible, whose influence has been felt in every corner of Western life, from law and literature to architecture and agriculture. No civilization ever rose to greatness on the back of TikTok tutorials alone.

Of course we need welders, electricians, mechanics, and cybersecurity experts.

Heaven help us if the power goes out and none of them are around. But if their education stops at the purely practical—if they never meet Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, Cervantes, or work their way through history from Herodotus to Victor Davis Hanson—we will have done a great disservice. For then we’ll have trained only laborers and technicians, not citizens and thinkers.

A young person who reads the Odyssey will never look at a storm or a long road trip quite the same way again.

One who reads Don Quixote may laugh, but also discover the stubborn dignity of being out of step with the age. A reader of Shakespeare begins to understand that human folly is eternal, but so too is human greatness. And in Dante’s Divine Comedy—that strange, difficult book you can’t swipe away—one may even glimpse the possibility that life has both order and purpose.

The screens will always be with us.

They are useful. They are entertaining. But they are not formative. Books shape the mind the way work shapes the hands. Without them, the hands may still be clever, but the mind risks becoming a tool shed with nothing on the shelves but half-charged batteries.