By Rodger Morrow, Editor and Publisher

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

History, they say, is written by the victors. In Beaver County, history is written mostly by people trying to make deadlines. That may explain why some of the finer points have gone missing—or were never there in the first place. Still, let us stroll through the centuries, if only because nobody else will.

The Dawn of Time

Before Europeans arrived, there was Saucunk, a bustling Native village where, according to local legend, the chiefs met every Tuesday to complain about traffic on Route 65. The Delaware and Shawnee must have suspected they were on borrowed time, since fur traders kept showing up with the same bewildered expression tourists now wear at the Beaver County Mall.

George Washington passed through once on his way to Fort LeBoeuf. He took one look at the mud and went home to write in his diary, “Not prime real estate.” Later surveyors disagreed, proving that Washington was no better at land speculation than he was at dentistry.

The Fort Years

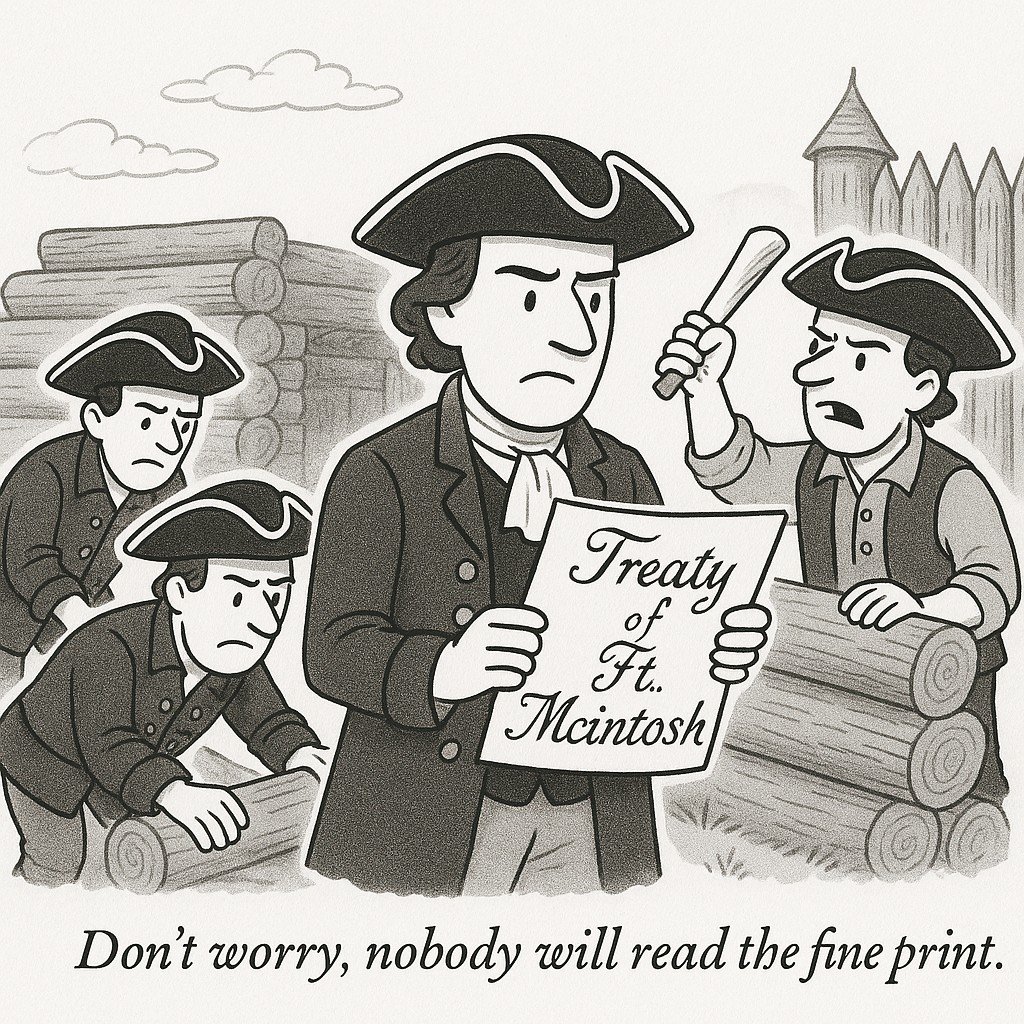

By 1778, the Revolution had crept this far west, and Fort McIntosh was thrown up in Beaver with all the permanence of a backyard treehouse. The soldiers, hungry and homesick, were ordered to hold the frontier. They did, though mostly by playing cards and inventing excuses not to patrol.

The fort’s great contribution to history was the Treaty of Fort McIntosh in 1785, a document that caused all parties to squint at the fine print, nod politely, and then ignore it. The fort itself eventually rotted away, leaving nothing but a historical marker, a DAR chapter, and a vague sense of obligation at every Fourth of July parade.

The Canal Era

By the 1830s, Beaver County had discovered the wonders of canal transportation: a system of watery highways connecting the Ohio River to the great elsewhere. Boats laden with coal and lumber floated sedately along while horses on the towpath did all the work.

Unfortunately, locomotives soon appeared—thundering, shrieking beasts that reduced canals to quaint mosquito farms. Canal pilots cursed the trains for frightening their horses, while passengers on the trains peered down and shouted, “Hey fella, get a move on!” The locomotives won, proving once again that progress is merely the art of going faster than your neighbor.

The Industrial Age

Then came mills, furnaces, and factories, which sprouted along the rivers like mushrooms after rain—if mushrooms belched smoke and made your shirts smell like sulfur. Aliquippa and Beaver Falls rang with the clang of steel, Midland smoked with chemicals, and Ambridge produced more bridges than one county could possibly need.

The names are legend: Jones & Laughlin, Babcock & Wilcox, St. Joe Lead. Beaver County became the sort of place where a man could get a decent wage, a house with asbestos shingles, and a summer vacation at Conneaut Lake, all for the low cost of emphysema by 55.

The Great Nap

By the late 20th century, the mills had dozed off, never to wake again. Whole towns discovered the economic benefits of nostalgia. Residents grew fluent in a new local dialect in which every sentence begins, “You should’ve seen this place in 1965…”

In Aliquippa, whole neighborhoods vanished. In Midland, the air cleared up so completely people could see Ohio for the first time and wondered if that was really an improvement. In Beaver Falls, the closing of the steel mills created the paradox of too many football players and not enough jobs.

The Energy Gambit

Shippingport entered the nuclear age in 1957, which seemed futuristic at the time, though most locals still preferred coal because it came with an honest layer of soot. Later, the Bruce Mansfield coal plant rose across the road, belching smoke and prosperity until it was retired in 2019. Nuclear power, however, still hums away at Beaver Valley, a reminder that progress comes in kilowatts and evacuation plans.

The Modern Era

Today, the county is home to cracker plants, Bitcoin miners, boutique breweries, and the eternal promise of broadband internet that never quite reaches your house. Economic development officials assure us that prosperity is just around the corner. Unfortunately, the corner is usually in Pittsburgh.

Still, Beaver County endures. It may not be Yoknapatawpha, but it has its own stubborn charm: a place where you can still get a fish sandwich big enough to feed an army, and where every town claims to be five minutes from the Turnpike, even if you’re clearly stuck behind a coal truck in Shippingport.