By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher

Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

Beaver County has always been green.

Sometimes naturally so—forests, meadows, pawpaws. Sometimes unnaturally so—garlic mustard, Japanese knotweed, and the occasional paint spill in the river. From Devonian ferns to suburban deer-resistant hostas, our flora has staged one long costume party, and we’ve been alternately the decorators, vandals, and accidental exterminators.

Ancient Roots: Ferns Before Fords

The county’s botanical resume begins long before steel or Sheetz. Fossils in Ambridge and Cannelton record the leafy ambitions of Devonian plants—ferns, lycophytes, and other greenery that had the audacity to crawl out of the water and try their luck on land. By the time settlers arrived, Beaver County was draped in what botanists called the Oak–Chestnut Forest. Towering chestnuts ruled until a blight came along in 1908 and turned them into firewood. Oaks, maples, and tulip poplars picked up the slack. Along the riverbanks, sycamores spread their patchy arms as if to say: Well, somebody has to hold this place together.

Enter the Settlers: From Harmony to Havoc

When Europeans showed up, the trees disappeared faster than pierogies at a church picnic. Corn, wheat, and apples muscled in. The Harmonists at Old Economy Village went one better: four acres of Teutonic garden perfection. George Rapp, the group’s charismatic leader, wasn’t just a preacher—he was part horticultural showman. Think Versailles, but with more sauerkraut. Boxwood-lined quadrants, orchards, grape arbors, roses, figs, herbs, even an early greenhouse: it was Eden on the Ohio. Visitors were stunned to find frontier farmers in Pennsylvania cultivating tulips like Dutch princes. Today the gardens remain one of the county’s best-preserved reminders that botany can be equal parts science, faith, and stubborn German neatness.

And then came John Chapman—better known as Johnny Appleseed—padding through the Ohio Valley with a sack of seeds, establishing orchards from western Pennsylvania into Indiana. He wasn’t planting dessert apples for your grandmother’s pie, mind you. His trees produced the kind of bitter little apples best suited for hard cider, which was frontier America’s Gatorade. Beaver County was one of his many waystations, where settlers drank what the orchards gave them and gave thanks that it was strong enough to make them forget how drafty the cabins were.

Industrial Shadows

Then came the mills, with their generous offerings of smoke, soot, and runoff. The Beaver River turned the color of mystery soup. Plants like Tennessee pondweed vanished, and even the weeds looked nervous. The chestnut blight finished off the county’s arboreal aristocracy, leaving tulip poplars to preside over second-growth woods like substitute teachers.

Blooms, Rarities, and Pawpaw Dreams

And yet, the county still blooms. Raccoon Creek’s Wildflower Reserve boasts over 700 species—trilliums, bluebells, jack-in-the-pulpit, plus show-offs like snow trillium and harbinger-of-spring. Some rarities cling on: purple rocket, vase-vine leather-flower, and heartleaf meehania, which sounds like a tropical cocktail but is actually a plant hiding in Brady Run.

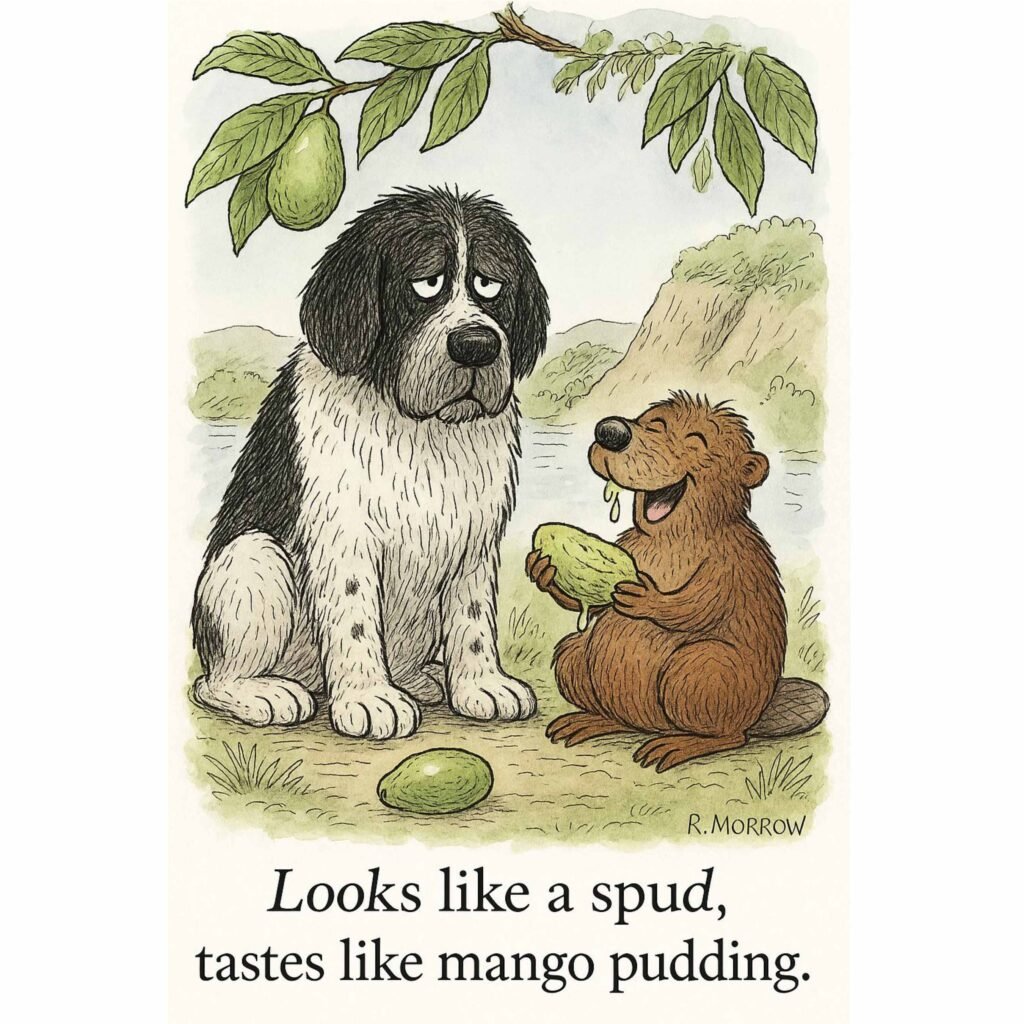

Then there’s the pawpaw. George Washington supposedly chilled pawpaws in ice for dessert at Mount Vernon, and frontier families packed them as trail rations. Thomas Jefferson sent seeds to Europe, trying to impress the French with America’s tropical-tasting fruit. Closer to home, pawpaws thrive along Beaver County’s river bluffs. In the 1940s, a local enthusiast in Aliquippa turned his property into a “pawpaw sanctuary”—long before “food forest” was a buzzword. Its current status is anyone’s guess, but for decades it stood as the Rust Belt’s answer to the Amazon. Each September, these green-skinned custard bombs still ripen in the wild, waiting for anyone with the nerve to eat something that looks like a potato but tastes like mango pudding.

The Green Invaders

Of course, no Beaver County story is complete without a few bad actors. Garlic mustard tricks butterflies into kamikaze egg-laying. Japanese knotweed builds bamboo jungles behind gas stations—though, to be fair, the bees love it and the honey tastes surprisingly good, like nature’s apology note. Multiflora rose spreads like the county’s least favorite groundcover. Add lanternflies, woolly adelgids, and the occasional beaver dam flooding a cornfield, and you’ve got a full cast of troublemakers.

Conservation and the Road Ahead

Still, hope persists. Local groups hawk native plants at farmers’ markets, the courthouse sports a demonstration garden, and Penn State Beaver studies endangered bleeding hearts that don’t just exist on Instagram. Volunteers wage war on invasives. The county conservation district warns us not to let deer eat everything in sight.

If we get this right, Beaver County could parlay its botanical riches into eco-tourism, specialty orchards, and a reputation as the Rust Belt’s green belt. If we don’t, well, there’s always knotweed honey.