Part 2: Coal, Oil, Shale, and Gas

By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher, Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

Coal: The Black Backbone

Geologists like to say Beaver County was born in the Pennsylvanian Period some 300 million years ago. Locals will tell you it was born the first time somebody figured out you could dig up black rock and get paid to set it on fire. Both are true, though only one kept the furnaces lit and the bar tabs paid.

Coal seams — Pittsburgh, Upper Freeport, Kittanning — ran beneath our feet like a secret inheritance, waiting for a generation of miners with strong backs and limited career options. By the 1800s, coal was rolling out of the ground and straight into locomotives, barges, mills, and parlors, where it heated everything except family arguments.

Companies like Imperial Coal were among the big players in Western Pennsylvania, though the oft-quoted claim of a 3,000-acre Beaver County operation looks more legend than ledger. Still, mining here was robust, with towns like Cannelton putting their name on cannel coal, a rare variety that made Victorian gas lamps glow almost cheerfully.

The industry peaked early, then coughed its way into decline. By the 1960s, annual output barely filled a few barges, and the Bruce Mansfield Power Plant became coal’s last grand fling before it too swapped black dust for natural gas. The seams remain, but the glory days don’t.

Oil: A Black Gold Boomlet

If coal was the steady breadwinner, oil was the fast-talking cousin who blew through town with pockets full of cash and left just as quickly. The first strike came in December 1860 at Smith’s Ferry, when drillers struck oil at 180 feet and kicked off Beaver County’s brief boom.

Wallace City grew up overnight, its wells gushing so hard the No. 2 Wallace cranked out 1,400 barrels a day. For a while, Hopewell Township and Glasgow were buzzing, and the Economy oil field pumped as much as 45,000 barrels a day during its best years. By 1910, though, the gushers had turned into drizzles, and Wallace City joined the county’s long list of ghost stories. Still, for a few decades, oil gave locals a taste of speculation, wildcatting, and the eternal hope that the next farm field hid Texas under its topsoil.

Shale: The New Giant

Shale was always there, brooding underfoot, waiting for technology to catch up. In the Devonian Period it was algae and plankton sinking into mud. By the 1930s geologists were mapping it, but nobody had the tools to unlock it. Then came the 2000s, horizontal drilling, and hydraulic fracturing — and suddenly Beaver County was a global energy player again, though not everyone applauded the honor.

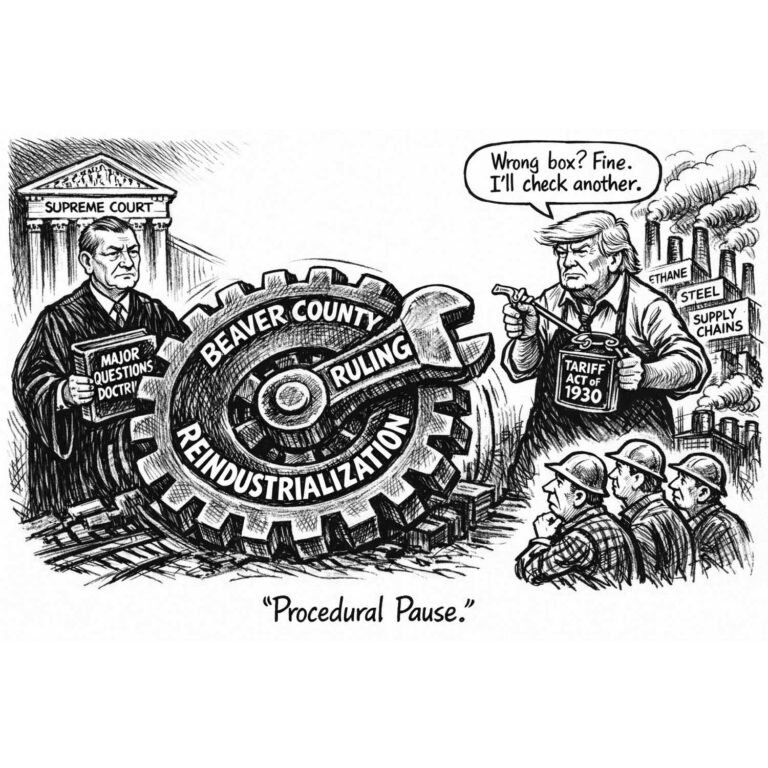

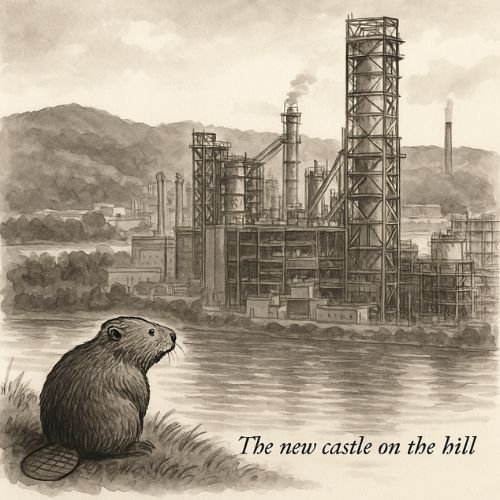

The Marcellus Shale turned out to be a jackpot, rich in methane and “wet gas” liquids like ethane, which Shell promptly converted into a cracker plant in Monaca. The original estimate was $6 billion, but like any castle built in modern times, the final bill came closer to $14 billion — proving that cost overruns are the one energy source we’ll never run out of.

Natural Gas: Yesterday’s Footnote, Today’s Powerhouse

Natural gas started out as the byproduct nobody asked for, bubbling up from 19th-century oil wells and occasionally lighting a lamp or two. Then it disappeared into the background until the Marcellus boom made it king. By 2008, rigs were humming and permits stacking higher than courthouse deeds.

Exactly how many permits Beaver County has seen depends on who’s counting — estimates run into the thousands, but the 1,400 figure often cited is more rule of thumb than audited account. What’s certain is that millions of cubic feet now flow daily through pipelines, most of it heading out of state, leaving locals to wonder whether they got jobs, royalties, or just the traffic jams.

Facilities like MarkWest’s Harmon Creek plant process the flow, while Shell’s cracker turns ethane into plastic pellets bound for ports. Gas has replaced coal as Beaver County’s energy backbone — though whether it will also inherit coal’s curse of boom and bust remains to be seen.

By the Numbers

- 300 million years – Age of Beaver County’s coal seams.

- 1860 – First oil strike at Smith’s Ferry.

- 1,400 (approx.) – Gas well permits cited for Beaver County, though precise tallies vary.

- $14 billion – Final cost of Shell’s cracker plant in Monaca (up from the $6 billion estimate).

- 168,215 – Beaver County population in the 2020 census.

- 175,000 – Approximate peak population, reached in 1950.

Boom, Bust, and the Bill

Energy made Beaver County famous, or at least solvent. Coal built the steel mills, oil built a few boomtown schools, and gas still hands out lease checks. But each payday came with its own hangover. Coal left black lung and busted towns. Oil left ghost derricks. Gas has given us jobs, lawsuits, and a plastics plant the size of Rome.

The population didn’t actually “peak in the 1920s” — that’s nostalgia talking. Census records show it topped out around 175,000 in 1950, before sliding to today’s 168,000. The resources come and go, but the people keep weighing opportunity against asthma inhalers. In Beaver County, the energy story has always been a deal with the rocks — and the rocks always hold the better lawyers.

The Punchline

Coal, oil, shale, gas: our inheritance from the ancient seas, passed down like a family heirloom that keeps burning holes in our pockets. One generation’s miracle fuel becomes the next generation’s cleanup bill. But through it all, Beaver County soldiers on, equal parts proud and skeptical. Around here, the geology may be ancient, but the punchline is always fresh.