Part Five: Negotiation, Beaver-Style

By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

Early Foundations: Fur, Forts, and Fragile Treaties

Beaver County was born in negotiation — often messy, often one-sided, but always consequential. The Beaver Wars (1650–1701) turned the Ohio Valley into a contested crossroads, as the Iroquois pushed out rivals and signed agreements like the Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1768). That deal cleared land for British speculators while pushing the Lenape and Shawnee into tighter corners. Representatives of those tribes were present at the negotiations, but they were not signatories and had no real role in the Iroquois’ sale of their homeland — which made it less a treaty than a real estate transaction conducted by absentee landlords.

Closer to home, the Treaty of Fort McIntosh (1785) marked one of the earliest formal U.S. efforts to secure territory in the Ohio Valley. Signed at the confluence of the Ohio and Beaver Rivers, it was intended to create peace and open land for settlement, but mostly it guaranteed years of legal wrangling and bad faith. The ink barely dried before Pennsylvania promised parts of the land to Revolutionary War veterans as ‘Depreciation Lands,’ prompting endless lawsuits and surveys as settlers tried to prove whether their title came from a grant, an improvement, or just the stubborn fact that they’d built a cabin first.

Then came General Anthony Wayne’s victory at Fallen Timbers and the Treaty of Greenville (1795), which ceded vast Ohio Valley tracts to the U.S., ending Native resistance north of the river. Out went the tribal claims, in came the Scotch-Irish farmers, the German millers, and the surveyors with their chains.

Negotiating a County Into Being

By the turn of the 19th century, the question was no longer who owned the land, but how to govern it. Western Pennsylvanians, weary of trekking to Pittsburgh for court sessions or tax business, pressed Harrisburg for a new county carved out of Allegheny and Washington. The result was a compromise born of lobbying, petitions, and boundary wrangling. On March 12, 1800, the Pennsylvania legislature approved the creation of Beaver County. Its seat was set at Beaver Town (later just Beaver), chosen because it sat neatly at the confluence of rivers and roads — and because no other borough could win enough friends in Harrisburg to get the nod.

Even this seemingly simple act involved disputes over ‘Depreciation Lands’ promised to Revolutionary veterans, overlapping claims between settlers, and the delicate matter of drawing township lines. The General Assembly had to referee the conflicting interests of speculators, farmers, and early millers before Beaver County could exist as a legal entity.

In short, our county itself was a negotiated settlement — less like a declaration of independence than a peace treaty between factions who finally agreed it was easier to form a county than to keep suing each other.

Industrial Ascendancy: Lunch Pails and Legal Precedents

The 19th century brought a new kind of bargaining — between owners and workers. A notable early skirmish came in 1872 at the Beaver Falls Cutlery Co., where white workers struck, only to see the company import Chinese laborers. The uproar reverberated far beyond Beaver Falls, feeding into the debates that culminated in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Beaver County had, in its way, helped write federal immigration policy.

By the early 20th century, the county’s industrial boom made negotiation unavoidable. Glassworks in Rochester, clay mines in Industry, and above all, Jones & Laughlin Steel in Aliquippa turned Beaver into a union crucible. Brutal conditions and 12-hour shifts created fertile ground for the Steel Workers Organizing Committee (SWOC), which clashed with management in the 1930s. The fight reached the U.S. Supreme Court in NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel (1937), which upheld the National Labor Relations Act and affirmed the right to organize. That ruling, born in Aliquippa, reshaped labor relations nationwide.

Workers followed up with a strike in May 1937 that forced management to concede representation, higher wages, and shorter workweeks. Collective bargaining no longer meant survival; it meant the promise of a middle class.

Decline and Adaptation: Negotiating the Rust Belt Retreat

Negotiation wasn’t always about victory. By the 1970s and ’80s, global competition gutted Beaver’s industrial core. When LTV Steel shuttered Aliquippa Works in 1984, 8,000 jobs vanished overnight. Local bargaining shifted from demands for overtime to pleas for retraining and severance.

The Experimental Negotiating Agreement (1973) had promised labor peace in exchange for job guarantees, but foreign imports overwhelmed it. The Reagan administration arranged steel import quotas; the USW wrangled for buyouts and retraining programs; state and federal officials hammered out diversification grants. These talks couldn’t save the mills, but they cushioned the collapse, letting Beaver County pivot into education, health care, and logistics. Negotiation, in this period, meant managing retreat with dignity.

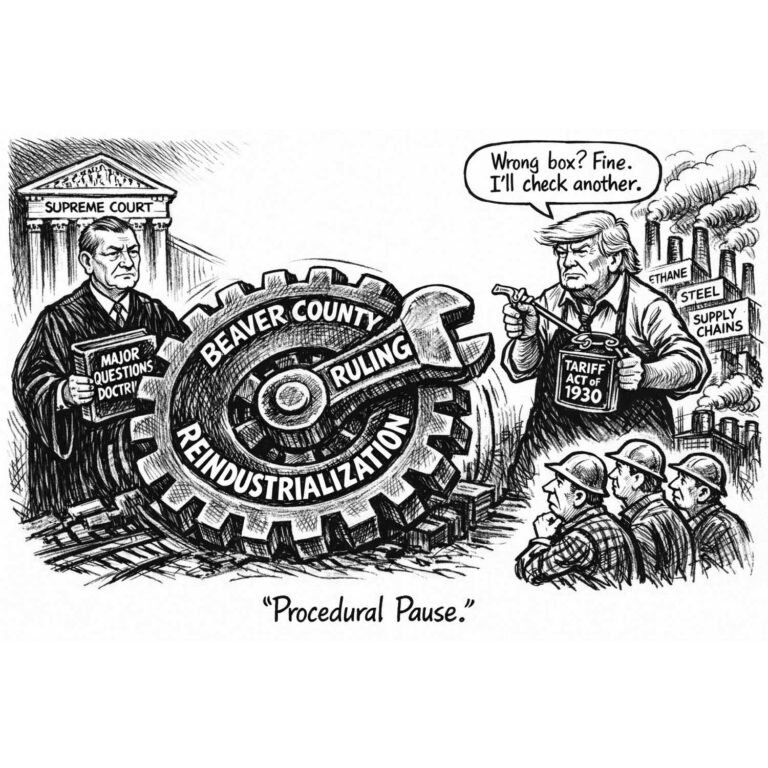

Contemporary Battles: Tariffs, Data Centers, and Township Cease-Fires

Today, negotiation ranges from trade wars with China to zoning fights in Brighton Township. Washington announces steel tariffs — 25% under Trump, higher still under Biden, doubled again under Trump redux — while locals debate whether these ‘victories’ preserve jobs or just make car prices worse.

Meanwhile, Beaver negotiates its future in energy and tech. The Shippingport Power Station is reborn from coal to natural gas to data centers. County leaders haggle over broadband expansion as though the fiber-optic lines were the Suez Canal. The Chamber of Commerce’s press releases often read like cease-fire agreements between warring small-business factions.

And, of course, unions remain a player, pressing for ‘Buy American’ clauses in green steel projects, even as the county adapts to post-industrial realities.

Our Own Geneva Convention

From the Beaver Wars to the Beaver Falls Cutlery strike, from the Treaty of Fort McIntosh to the tariffs of 2025, negotiation has always been our local survival strategy. Sometimes it carved up rivers, sometimes it secured 40-hour weeks, sometimes it just prevented another empty mill from turning into a strip mall.

The rest of the world can keep its Geneva Conventions. Beaver County lives by a simpler rule: if you can get the steelworker, the schoolteacher, the small-business owner, and the state senator to sit down over coffee at the Café Kolache, you’ve done more than most foreign ministers ever manage.

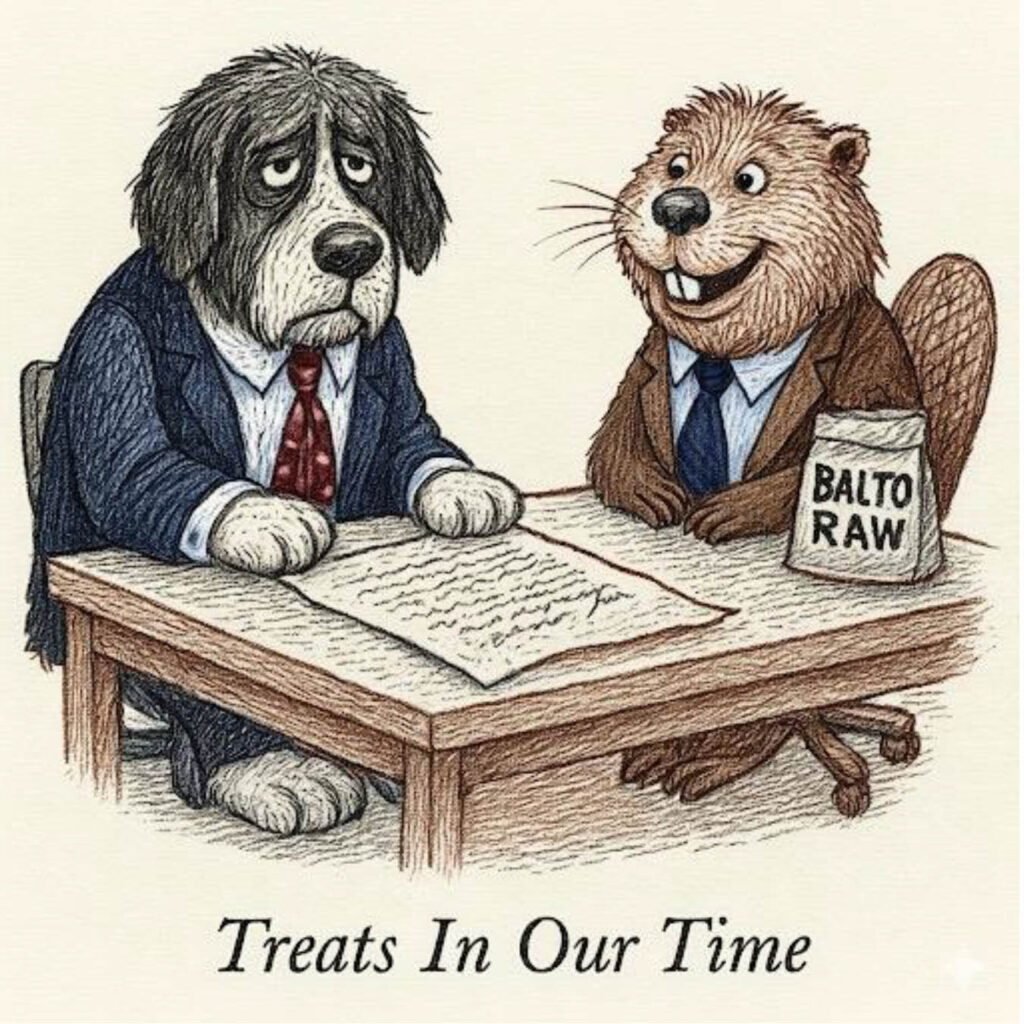

And if Seamus the Newfoundland and our scruffy beaver mascot manage to hammer out another deal over a bag of Balto Raw dog treats, well — call it Treats in Our Time.