By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher, Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

A Modest Chronicle of Twinkling Lights, Steel Paychecks, and Cookie Tins.

Start in Beaver Borough, the county seat that always fancied itself a smaller, better-pressed Pittsburgh with a river view. Third Street in the 1940s and 50s was a holiday postcard left out on the stoop: red bows tied to every gas lamp, the courthouse clock glowing like it had swallowed a Christmas bulb, and Kaufman’s, Penney’s, McCrorey’s, and Beaver Drug keeping their lights on until 10 p.m. so steelworkers coming off swing shift could stumble in to buy a necktie or a bottle of Evening in Paris. Horse-drawn sleighs clopped along on the Saturday before Christmas, performing the civic service of making motorists feel guilty for having cars. The air smelled of roasted chestnuts from a cart stationed precisely where the December winds came tearing off the river and attempted hypothermia on your ankles.

Christmas used to arrive in Beaver County the way freight trains used to roll into Rochester—loud, punctual, and with no regard for anyone’s nerves. Before Amazon began treating Darlington Road like a personal slalom course, December began with the first mill whistle at J&L and ended when the last pizzelle iron finally cooled sometime after New Year’s Day. Back then, Christmas wasn’t an errand. It was a county-wide pulse you could set your Timex to.

In Rochester, Christmas arrived with a little theatrical flair. Local lore insists that Santa occasionally stepped off a Pittsburgh & Lake Erie passenger car, waved from the observation platform like a pocket-sized Eisenhower, and was chauffeured up Brighton Avenue in a convertible as if he were late for a political rally. Whether this happened every year or only in the fondest memories of men now in their eighties remains part of the charm. What is certain is that Rochester’s stores—Murphy’s, Penney’s, and (later) a branch of Kaufmann’s—buzzed with enough holiday commerce to convince a passerby that Santa had taken out a second mortgage.

Cross the river to Monaca and the scent changed. G.C. Murphy’s roasted cashews perfumed the doorway. Phoenix Glass workers sold hand-blown ornaments at prices that suggested they’d brought them from home. St. John’s church ladies produced nut rolls so long they required two parishioners and a prayer to get them to the car. Monaca’s 1960s Christmas Village—those plywood chalets along Pennsylvania Avenue—was where half the county bought handmade wreaths and the other half disputed the authenticity of their neighbor’s babka.

Exit the Turnpike on Route 18 and you soon found yourself on Seventh Avenue in Beaver Falls, which glowed each December with all the enthusiasm of a department-store window display. Benson’s and Montgomery Ward’s anchored the street, their neon signs shining like twin beacons of mid-century optimism. Old-timers recall smaller stores—Berkman’s, Caputo’s, Fashion Hosiery, and Allan Jewelers—where teenagers browsed engagement rings before retreating to the soda fountain at Moretti’s Drug Store for courage.

And then there was Bonnage’s, as legendary in Beaver County as snowfall in December. Children pressed their noses to Bonnage’s windows to marvel at the displays—electric trains circling cardboard mountains, dollhouses lit like mansions, tin robots whose futures lay in closets by January. What the windows didn’t reveal was even better: inside, Bonnage’s was packed from basement to attic, an overflowing vertical wonderland where every square foot—stairs included—groaned under the sheer volume of toys. Parents entered bravely and exited carrying parcels, debt, and the creeping suspicion they had spent more than intended, which of course they had.

Nearby stood Providence Hospital, where generations of Beaver Countians arrived squalling into the world and were later treated for injuries sustained while assembling Christmas-table hockey games. The hospital’s brick façade caught the December light in a way that made even medical bills look slightly festive.

Giant silver bells hung over Seventh Avenue with the confidence of steel rivets. The Salvation Army band played nightly. And when the municipal Christmas tree lit up in front of the Carnegie Library, motorists stopped on Route 18 to watch, creating a holiday traffic jam festive enough to be forgiven.

A few miles up the river, New Brighton became “Christmas Lane.” Merchants had begun stringing overhead lights as early as the 1920s—at least according to New Brighton boosters, who never miss an opportunity to mention it. By the 1950s, the animated Boston Store windows and towering tree drew crowds from Rochester, who pretended they weren’t crossing the river for the express purpose of gawking. Bakeries like D’Onofrio’s, Klančar’s, and Pagano’s produced potica, pignoli, and sponge candy so addictive that dentists secretly prayed for snow days.

Farther down the Ohio, Ambridge transformed into a seasonal Little Europe. Merchant Street glowed with anise, walnuts, and a level of woodsmoke that would now require a permit. Lauf’s, Kaufmann’s Economy Store, and a constellation of church-basement bake sales filled the town with Greek kourabiedes buried under powdered sugar avalanches, Croatian kiflice rolled with surgical precision, and Serbian nut rolls that evaporated the instant they hit a plate. Santa, out of necessity, was multilingual.

And then there was Aliquippa, where Christmas burned brightest. When J&L paid its Christmas bonus, Franklin Avenue turned into a human river. Cox’s, National, Wolen’s Men’s Shop, Murphy’s—every sidewalk shoulder-to-shoulder, every cash register ringing like salvation. Santa roared down the avenue on a J&L fire truck, sirens blaring in the key of retail. Layaway windows bulged with bicycles and doll carriages bearing mothers’ names. In the Plans and the Terrace, kitchens turned out fig cuccidati and walnut rolls rich enough to require string for slicing. The smell of anise drifted uphill until even the deer took notice.

Even tiny Midland refused to be left out. Midland Avenue had McCartney’s with its proudly advertised escalator, Fischer Brothers’ five-and-dime, and decorations so dense the sky was essentially optional. Steelworkers marched in the Christmas parade carrying torches made from mill scrap—an OSHA nightmare, but visually delightful.

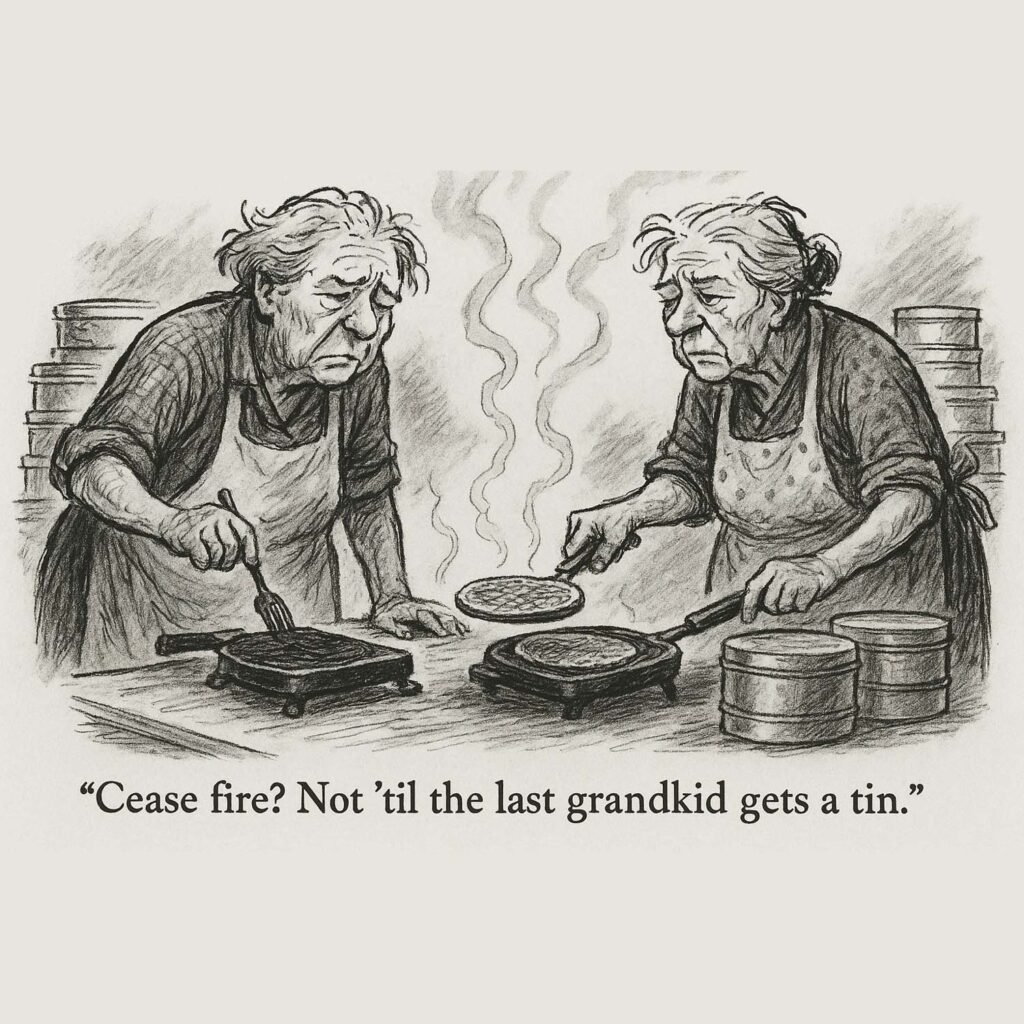

Across every borough, the same rituals echoed in a hundred accents. Italian pizzelles hissed in New Brighton and Aliquippa. Slovak grandmothers in Monaca and Ambridge rolled dough thin enough to read through. Polish piernik perfumed Koppel and Conway. Serbian strudla braided itself through Aliquippa’s Plan 12 while the radio crooned “Božić u Mom Kraju.” Greek kourabiedes disappeared under blizzards of powdered sugar. And every mailbox—Welsh in Vanport, African-American in Linmar Terrace, Lebanese in Baden—received at least one cookie tin for the mailman, the priest, or the neighbor who shoveled your walk.

Then came the malls. Then came the layoffs. The big stores dimmed one by one, as if someone had blown on a row of birthday candles. Wards left Beaver Falls. The mall was bulldozed. But the heart kept beating—still beats.

Stand on Franklin Avenue on the first Friday of December and you’ll find the same anise in the air. Fifth Avenue in New Brighton still wraps its trees in white lights. Rochester still tunes up the band. Beaver’s courthouse still glows like a nostalgic nightlight. And somewhere—a Formica table, a grandmother, and a ten-year-old learning a sacred family secret—a pizzelle is being flipped before it burns.

Because Christmas in Beaver County was never about the presents. It was about the whistle that said the money was coming, the lights that said the town was alive, and the cookie tin passed over the fence that said you belonged.

That part, thank heaven, hasn’t changed at all.