By Rodger Morrow, Editor & Publisher, Beaver County Business

Listen to a podcast discussion about this article.

When Wall Street Comes to Dinner

Beaver County has been eaten by many things over the years: steel mills, recessions, that strange river fog that settles in every October and refuses to leave until you’ve wiped the car windows twice. But nothing chews quite as relentlessly—or as noiselessly—as Wall Street private equity, which drifts into the Valley like a polite relative, shakes hands all around—then quietly makes off with the family silver.

It’s not that private equity sets out to be the villain. Heaven forfend. The villainy is entirely accidental, the way a raccoon knocks over your garbage cans at 3 a.m. It isn’t malicious, merely opportunistic. If you leave the lid unlatched, well, what did you think was going to happen? Raccoons gotta raccoon, and private equity has to squeeze EBITDA until it wheezes for mercy.

The Valley’s Hidden Feast

The reason this keeps happening—to New Brighton foundries, to Aliquippa manufacturers, to Rochester engineering firms—is simple: the Beaver Valley is rich in things private equity finds delicious. Not coal. Not steel. Something rarer. Aging companies with proud histories, loyal employees, and just enough profitability to be irresistible.

To a Wall Street dealmaker, a company like this sends the same dopamine signal that a hot doughnut sends to the human brain. The pupils dilate. The heart rate increases. Advisers begin circling. Seminars are scheduled. Slide decks are burned through at an alarming rate.

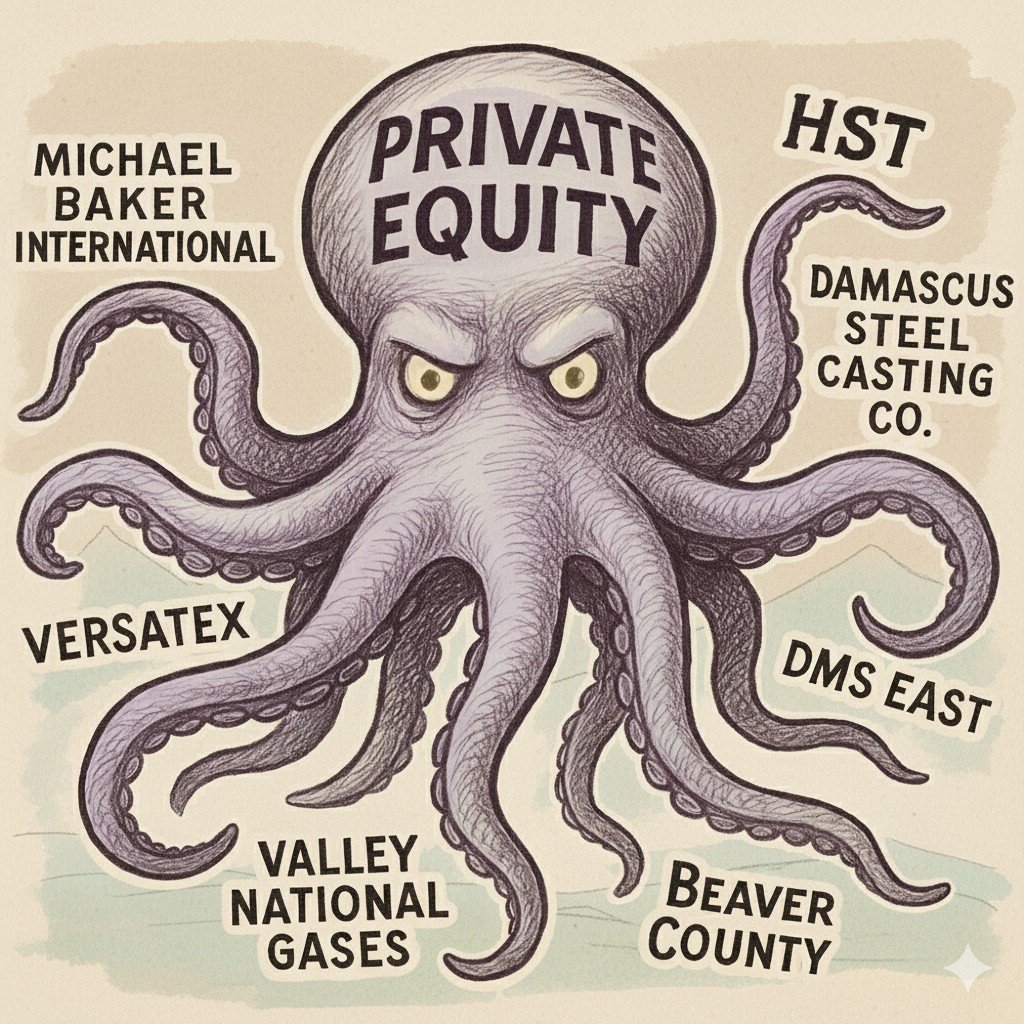

Suddenly, a 117-year-old New Brighton steel foundry becomes a “specialty metals platform.” A Rochester engineering icon becomes a “mission solutions integrator.” A Beaver County billing service becomes “non-core vertical whitespace ripe for synergistic consolidation”—which is finance-speak for “We think this thing might print money.”

The Python and the Deer

Once the acquisition papers are signed, private equity behaves exactly as you’d expect from an industry that congratulates itself for removing the last remaining office plants to streamline workflow. The first order of business is to borrow several fortunes and deposit it, lovingly, onto the company’s balance sheet. This is known, in the refined language of financiers, as “creating efficiency.” To the rest of us it looks very much like a python wrapping itself around a deer.

Next comes “optimization.” Around here that word has the same connotation as a thunderclap.

You may recall what happened to Damascus Steel Casting Company, a New Brighton fixture since Theodore Roosevelt was doing push-ups in the White House. After a PE-backed roll-up, the plant was shuttered, the manufacturing operations shipped to something called Temperform in Michigan, and Beaver County was left with one fewer smokestack to point to when telling the grandchildren, “That’s where your granddad worked back when America built things.”

Then there’s Versatex, once a Highlander Partners portfolio darling, now an Aliquippa stronghold under corporate ownership. Or Healthcare Support Technologies in New Brighton, quietly absorbed by Phoenix-headquartered UnisLink (itself backed by Boston-based PE firm Riverside Partners). Or DMS East in Freedom, part of a national private-markets marketing platform whose owners you’re more likely to find in Houston or Boston than at the counter of the Brighton Hot Dog Shoppe.

When the Monster Knocks Politely

All perfectly legal, of course. All perfectly rational. But to Beaver County residents, who grew up believing that businesses existed to make things, employ neighbors, and sponsor Little League teams, the new “value creation strategies” feel suspiciously like the plot of a horror movie in which the monster knocks politely before devouring the house.

Why does Wall Street keep eating the Valley? Because Beaver County is full of companies that have done the unfashionable thing: they survived. They endured recessions, foreign competition, the closing of the Aliquippa Works, the rise of the internet, the fall of the mall, and the ever-present risk of being replaced by a strip plaza.

These survivors may not be glamorous, but they produce cash flows with the regularity of a Presbyterian potluck. And to private equity, a predictable cash flow is the financial equivalent of a steak dinner served on a silver platter by a waiter whispering, “Would you care for another glass of the Merlot?”

The Time Preference of Money

Meanwhile, local ownership—once common—has become as rare as a good parking space at Walmart on a Saturday. The grandchildren don’t want the business. The founder wants to retire. The bank wants out. And private equity is always ready with a checkbook and a PowerPoint promising “partnered growth initiatives,” which is what you get when you cross MBA grammar with a thesaurus.

Is private equity always bad? No. Some firms genuinely improve companies. Some add technology. Some rescue businesses that would otherwise collapse under their own sentimental weight. More than one Beaver County operation has been saved— not savaged—by outside capital.

But after enough plant closures, leveraged buyouts, and “consolidation synergies,” people here can be forgiven for assuming that Wall Street shows up with a bib already tied around its neck.

Economists have a polite term for Wall Street’s impatience: the time preference of money—which is a fancy way of saying that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow, and a dollar next week might as well be a rumor. This simple truth, discovered sometime around the invention of goats, drives private equity to behave like a teenager with a paycheck burning a hole in his pocket. The faster the return arrives, the more valuable it is, which is why PE firms push companies to “accelerate value creation,” a phrase that usually involves removing anything that can’t be monetized by Friday.

It isn’t that they hate long-term thinking; it’s just that long-term thinking doesn’t clear the hurdle rate. And so Beaver County businesses, built over generations, find themselves judged by an industry that treats time not as a season for growth but as an enemy to be conquered with spreadsheets and leverage.

The Valley Fights Back

So in the end, the reason private equity keeps eating the Valley is the same reason the Valley keeps being eaten: we produce things worth buying, and they produce ways to buy them with other people’s money. It’s an old story, really. Our grandparents built Beaver County. Our parents kept it running. And now, somewhere in Manhattan, a whiteboard lists our remaining midsize manufacturers under the heading: “Q4 Targets—Low-Hanging Fruit.”

If history is any guide, Wall Street will keep eating as long as the Valley keeps cooking. Fortunately for us, Beaver County has always had a habit of growing back what gets chewed away—foundries, businesses, ideas, and now, apparently, cartoons of giant octopuses clutching once-vaunted corporate names. Even private equity can’t digest that.